"We now know that colonialism is alive and kicking." The renewal of AfricaMuseum in Matthias De Groof's movie

DocLisboa’s “Decolonizing Memory” session featured two films that problematize colonialism. Palimpseste du Musée d”Afrique (world premiere) by Belgian Matthias De Groof and A Story from Africa by African by the American director Billy Woodberry. We interviewed De Groof, director and researcher for whom “theory without practice is empty and practice without theory is blind.” The object of his film is the attempt to decolonize a quintessential colonial symbol: the Royal Museum of Central Africa in Tervuren, Belgium, which opened as AfricaMuseum in 2018 after five years of restauration.

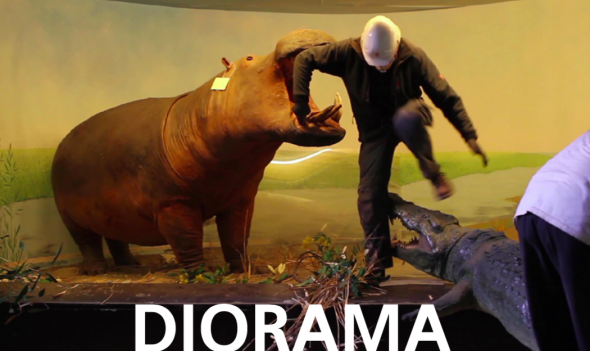

At the beginning of the film, the story is already told to the children considering the “other side”, the African side. We witnessed the dismantling of the colonial showcase: smashing shop windows with dusty artefacts, unwrapping animals, cataloging masks, peeling off dioramas and phrases about the empire’s “civilizing” mission, removing statues like the one of King Leopold II and the Paul Wissaert’s L’homme-leopard 1913. We follow the discussion of experts from African organizations who ask, for example, how to make a critical reading of the history of this museum not only by discourse because images have more impact on the visitor? Above all, they ask themselves: what is the position of the museum whose mission is also anti-racist and pedagogical? Showing both sides: Belgian and Congolese, the former colonialist and former colonized, is still not enough as a decolonizing gesture, they say. It is no longer correct to refer to Congo’s natural resources without counting the exploitation they entail, nor to display embalmed animals without criticizing the idea of nature domination. The position will surely be hybrid, of different voices, and full of ghosts in museum. The largest of all, by Leopold II himself (1835 - 1909), a private owner of Congo, implementing Belgian colonial exploitation focused on rubber harvesting, which would have cost millions of Congolese their lives in forced labor under a violent regime. We knew already there’s nothing like good colonialism.

On the one hand, we see the cathartic effort of the symbolic gesture of demolishing a colonial worldview. Decolonization of museums and the dispute over memory are the order of the day. In 2018, the Patrice Lumumba Square (1925-1961, Congolese anti-colonial leader, signed as prime minister after independence) was inaugurated in Brussels at the entrance of the Congolese neighborhood Matonge. On the other hand, we recognize with the author that “we cannot escape to Eurocentrism” and that colonialism resides in the matrix of museums (with national and imperialist identity designs), and whose collections consisted of samples of fauna, flora, artifacts, riches and mysteries of part of the world that was thought conquered.

The Congo Museum, created in 1898, was founded by King Leopold II a year after the 1897 Brussels Universal Exposition, whose “colonial section” took place in Tervuren. There, 267 Congolese “products” were exposed to cold living in gardens and canals around the palace (the well-known human zoos, fashionable in European metropolises), among which seven died of pneumonia. It continued as a cultural and scientific tool for the colonial service, and in the 1960s (the independence of Congo on June 30 of that year), as Royal Museum of Central Africa, it now has a more anthropological aspect. In 2013, it closed its doors to this large public investment operation, which, as Matthias De Groof leads us to think, did not change the paradigm of musealizing Africa and not coloniality.

De Groof has made other short films about the museum. Such is the case with the fiction Lobi Kuna, a Lingala expression (one of hundreds of languages spoken in the Democratic Republic of Congo) to say “the day after tomorrow”. In it, the Congolese photographer Mekhar Kiyoso sees through his lens the macabre museum as a mausoleum of his cultural heritage: being possessed by artifacts, he recalls the pain of having always been alienated from objects fundamental to his culture and identity. This refers to the transmission of history in the present DRC, where students complain that the manuals and history of their country still reproduce colonial historiography and western art history. The process of decolonization of memory is also taking its first steps there, notably by the debate over the restoration of African heritage and the opening in Kinshasa of the new National Museum of the Democratic Republic of Congo (June 2018).

I watched you in youtube saying that you had chosen to make a phd in NYU because of the scholars Manthia Diawara and Robert Stam. Now you’re a postdoctoral researcher studying postcolonial theory and cinema, right? How did your interest in African and postcolonial issues begin?

It started with a paradox. Listening to my grandfather’s heroic but nostalgic stories about him being a colonial doctor in Congo, I increasingly became aware that these stories echoed other stories about greed and terror. My grandfather’s stories were part of narratives justifying colonialism and realizing this was part of my self-decolonisation. What interested me, was this enormous tension between on the one hand being a doctor healing Congolese, sometimes by giving his own blood and thereby transgressing all racial boundaries; and on the other a system of exploitations based on racialized segregation. The Hannah Arendt questions came up: “how can you do evil without being evil”?

It seems to me that you cannot understand forms of colonialism, including contemporary ones, without taking these tensions and narratives into consideration. But in trying to understand how these contradictory narratives operate, I stumbled upon an intellectual impasse: simply put, you cannot escape Eurocentrism, since it integrates all oppositions to itself. This is why I desperately needed to hear other stories, those told by African filmmakers, proposing alternative worldviews, offering different gazes on their histories and societies. It was liberating!

From Royal Museum for Central Africa to Africa Museum: Are you happy with the result of AfricaMuseum? Why do you end the movie with the museum’s transformation costs? It shows a great public investment.

The renovation has at least one advantage: that you cannot have the illusion anymore that colonialism is something of the past. If you know that more than a million euros has been spent on the fountain only, that thousands have been spent on the renovation of the façade, including the countless numbers of Leopold II references, … you realize that the project was more about embellishing the biggest colonial monument in Belgium than it was about the decolonization of the institution, despite using decolonialism as rhetoric to justify this abusive use of taxpayer’s money. Correspondingly only 0.25% of the entire budget went to collaborations with the source-communities on rethinking the museum. When paying the ticket to enter the museum prior to the renovations, visiting dusty dioramas, you actually bought the illusion that colonialism was something outdated, something that belongs to history. Now, you know it’s alive and kicking. Much of these things, I have to add, go beyond the power of the museum, but is decided elsewhere, from parliament to government. It is thus really a societal question.

One of the other ways in which you see coloniality reemerge, is precisely in the mission the museum ascribes itself. “Africa” is an object of study while the idea of representativeness and the desire to be a window on a continent are the basic epistemological principles of imperialist logic. The scenography continues the “chosification” and “domestication” - two basic principles of colonialism - in the form of masks exhibited behind showcases and stuffed animals. The colonial logics of collecting is also pursued, but then in regards to contemporary art. However, I subscribe the mission of museums as, for instance, communicating scientific knowledge to a broad public. In this case, transmitting knowledge about how coloniality really works, would imply a “museum of colonialism” or a “museum of coloniality”. It would focus on the logics, derivatives and residues of coloniality, such as nowadays racism; and focus on its transformations, including in its aesthetics. It would tell the story of how the Anthropocene is in fact nothing more than colonized nature with uneven impacts distributed along postcolonial lines; and it would use geology as well as biology and humanities to tell this story.

Ana Naomi wrote in BUALA “those visiting when it re-opens will be confronted with the uneasy relationship between past and present that Tervuren will always embody - and with the lingering presence of King Leopold’s ghost”. You put the presence of the ghost in a text and voice by the Congolaise writer Jean Bofane. Why did you choose this kind of remembrance?

It’s indeed an interesting tension: the fact that you cannot decolonize a colonial institute, except if you put coloniality itself and its metamorphosis at the center of the debates. Leopold II is there, everywhere. It was his project, his museum… Meanwhile, he seems to whisper: “criticize me as much as you wish, but the fruits of my crimes are what you’re tasting”. In a sense, he – as is the museum – function sometimes as a scapegoat to deflect attention from the ways in which coloniality persists in our very cup of coffee or mobile phone. In the film, his statue is carried away; but his vision remains. Jean Bofane agreed to collaborate on the film, because the Congolese voice reflecting on these issues is necessary. And more than that, his literary talent elevates the film into a piece of art.

Who is looking at whom here? And whose story is being told here? - your questions that I give you back.

There is not one single instance looking and telling. I do so with my camera. My perspective is also present in the ways images collide, also thanks to my fantastic editor Sebastien Demeffe and Mona Mpembele with whom I collaborated. Jean Bofane’s point of view is added, with his words sometimes translating the points of view of the masks. The discussions amongst the experts also translate various perspectives and gazes. Ernst Reijseger, the composer too, interprets. But at the end, it is the spectator who looks and whose visions are influenced and altered by the film.

Joseph Gilungula - director of the Institute for National Museums of Congo - recalls that Tervurem must pay attention to the provenance of the 450,000 artifacts in his collection. Many of the objects were useful and part of the community, in religious ways like activating the relationship with the invisible world through objects and rituals. Do you think this is well marked in the Africamuseum discourse?

Even if the museum would describe the artefacts as such, they do not incarnate that ritual function. In fact, they perform another ritual function within the museum which is, after all, a ritual site. Historically, the museum became a ritual site of citizenship, progress, modernity and coloniality and the artefacts were exhibited to tell that cult. They were not only reduced to a modality of exposition; but their cultual function was transformed. This has not been changed fundamentally after the renovation of the museum, despite its discourse being changed into the empty political correctness of decolonialism.

To Pay tribute to the 267 dead Congoleses who had been exhibited like human zoo Universal Exhibition Brussels in1897. How is this story referred to in the museum? Was the movie part of a grieving process?

Showing the ceremony in the film was crucial for two reasons. First of all, the museum has been metaphorically built on that grave. The “human zoo” that made these victims, was so successful in regards to the numbers of visitors, that the idea of a permanent museum took form. In a way, the Royal Museum of Central Africa is a direct continuation of that exhibition which dehumanized humans and which gave the idea to the millions of spectators that the world is available to us, that the world is at our disposal (to be “civilized”). Secondly, the experts feel related to these victims. To Billy Kalonji, for instance, his engagement to change the museum from within, is a promise to these victims. It’s a matter of profound justice.

Palimpsest of the Africa Museum documents the renovation of the Royal Museum of Central Africa (now Africa Museum) by presenting it as a process of aesthetic mourning, highlights the complexity of its transformation and shows, through the eyes of the African diaspora in Belgium, the real challenge of its renovation: the decolonization of the Self.

Article published in jornal Público 18/10/2019