Cabral unblocked the road to independence, the task left to us was to pave it! An interview with Sana na N’hada

Accompanied by his charming serenity and wisdom, we learn about the unique and discreet career of Sana na N’hada, a big man who was at the heart of history. A Guinean director of Flora Gomes’ generation, he studied cinema in Cuba by chance, filmed the PAIGC guerrillas, was director of the National Film Institute of Guinea-Bissau (Instituto Nacional de Cinema e Audiovisual, INCA), and has made efforts to rescue and archive the images of the liberation struggle for the last 13 years with the artist Filipa César, with whom he collaborates on artistic and intervention projects. He did everything he could to produce films, almost always on a low budget and walking miles to fetch the film and have it developed.

He tells us about the important and complex mission that Amílcar Cabral delegated to them and what it was like to learn the crushing news of his assassination in the middle of this process. It fell to him as his first job to film Amílcar Cabral at an exhibition on the struggle in Conakry, in 1972, and then the transferring of his body to Bissau, capturing the commotion of the Guineans at the death of their greatest thinker and anti-colonial resistance leader. In 1973, Sana heard Ana Maria, Cabral’s widow, “as if I were dreaming, delirious - now the world seemed to be collapsing on my head,” tell how Amílcar, “even after being hit with the first shot, still wanted to know what was going on and why” he had been killed. Cabral’s dream and struggle may not die, but it’s hard for people like Sana to see the distance between his commitment and the country today. He fell into a depression at the neglect of the audiovisual materials. But in his essential meetings with Chris Marker and Sarah Maldoror and, more recently, with Filipa César, he realized that it was possible to work more autonomously.

Sana na N’hada is the best narrator of his own epic and of a historical context that will interest many. Our interview begins in September 2022, in the Malafo tabanca, near his home village, at the inauguration of the Abocha Media Library together with Filipa César, Marinho Pina, Suleimane Biai and the entire local community, to promote the exchange of knowledge. We continued between Bissau and Lisbon and finished it after the Colloquium ‘Amílcar Cabral and the History of the Future’ last month.

Sana with a camera and photometer. Bissau, 1976. Meeting in Praça dos Heróis Nacionais, visit by Agostinho Neto. photo by Agostinho Sá

Sana with a camera and photometer. Bissau, 1976. Meeting in Praça dos Heróis Nacionais, visit by Agostinho Neto. photo by Agostinho Sá

FROM MEDICINE TO CUBA

How did your life drift into cinema?

In 1963, I was thirteen years old and attending third grade at the Franciscan priests’ school in my village, Enxalé. When the war broke out, there was a firefight in the quarters of my tabanca and we fled with my siblings and my mom to the guerrilla base. We fled to take shelter for a week at most, we thought, but the conflict lasted eleven years. When the colonial conflict ended, everyone had a possible start in the civil service. People who worked at Radio Liberation could work at the National Broadcasting of Guinea-Bissau, it was an existing structure, there was no need to invent it, they just had to adapt to the new reality. In the field of cinema, we were four young people trained in Cuba, Josefina Lopes Crato, José Bolama Cobumba, Florentino Flora Gomes and I, and we had already been working for two years or so. Our role as filmmakers was unique, the first time it existed. So, when the war ended, we had to create something new and, in 1977, we prepared the statutes to create the National Film Institute.

Before studying film, you went through education and medicine, what was that like?

In 1964, at the PAIGC congress, they thought it necessary to establish the structure of the new state that would be created. The slogan was “let those who can read teach those who can’t.” Within this framework, I went to set up a school in the tabanca of Bumal. On the first day, 79 individuals showed up wanting to know how to read and write. Caetano Semedo, the guerrilla leader in that region, had asked my mother to take me with him to meet the guerrilla fighters. She didn’t accept it, but he took me anyway. And so, I taught and set up a school with people my own age. It was a huge responsibility. We made desks out of liana in the open, there were no notebooks to write the numbers nor a blackboard, so we would get planks instead. Then we didn’t understand each other linguistically, so I had to learn Manjak to be able to teach. It was easier for me to learn their language than for them to learn Balanta, my language. And so it was. At the end of the school year, during the rainy season, they gave me free passage to go to Conakry for an internship so I could teach. It took a week to go from here to the border, and I had to pass through Senegal to get to Conakry. But I had a bad foot and couldn’t walk.

At the time, could you only get around on foot?

Yes, of course, the war was everywhere. So I didn’t go because I was ill. Then they came to get me to go to Morés, I don’t know why. It turned out that Osvaldo Vieira, who was the military chief of that Front, remembered that he had promised to send me to Conakry, to the newly created Pilot School. When I arrived in Morés, he wasn’t there. I ended up at the Field Hospital, where Simão Mendes wanted grown men to teach the bare minimum to help the war wounded, who often died before reaching the hospital or arrived bleeding and almost dead. The aim of this internship was to teach first aid to soldiers who were old enough to fight. As I was only 15, Simão Mendes didn’t want me there, he said he wanted men, he “didn’t need babies.” But I’d spent the whole day walking to Morés, a day’s journey on foot, there was no way of getting back to where I’d come from. So, I had to stay at the hospital, where I worked conventionally, I did my internship with Simão Mendes, I finished it, my colleagues were distributed to other regions, but I stayed because I was underage. Then some Cuban doctors came and I remained with them. At the end of 1966, I arrived in Conakry to go to the Soviet Union where I would complete the lyceum and then study medicine. But I arrived late, the group I was supposed to join had left a week earlier. Amílcar Cabral said that our group could no longer work in medicine. There were six of us: four would work in agriculture, and the two of us (me and José Bolama Cobumba) would make movies. But I’d never seen any motion pictures before.

You hadn’t seen a movie? Not even a photograph?

No. The only image I knew was of Jesus Christ, from a catechism book, I hadn’t seen a movie.

How many years did you spend in Cuba?

Five and a half years, attending the lyceum and film training.

Apart from Cuba, how did Guinea support you?

There was no state, there were PAIGC guerrillas. The Cuban government received these students. Most of them went to the Soviet Union, Germany, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Morocco and Bulgaria. I went to Cuba, but there was no film school, instead there was an Instituto Cubano del Arte e Industria Cinematográficos (Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry), the ICAIC. So, we had to do high school very quickly. Only after that did we go to the Film Institute where we learned, in practice, the mechanism of a 35 mm camera, the German Arriflex. What it is, how it works, all on a tour of the ICAIC. Then we learned the structure of the film, the emulsion, the support, the silver salts for developing, all that theory. We even learned how to make photographs; we made kilometers of film. We’d go to the lab with a reel full of Kodak film, and with used empty rolls, we’d roll an average of 35 exposures and up to 70 photographs.

Do you still have material from that time?

No photographs, no, but some were published in PAIGC Actualités. What we did in Cuba stayed there. But some of the other images, which Filipa César helped to save, with funding from Germany, are here in the Media Library. After arriving in Conakry on January 7, 1972, we were sent for a training course at Actualidades Senegalesas, a state-owned company, but with no budget for us. We came back from Cuba with cameras, we had to do something. At weekends, we’d get away from Dakar to the border area and go to the guerrillas to take pictures. The guerrillas didn’t want us there, we weren’t combatants, we just got in the way, like dead cargo.

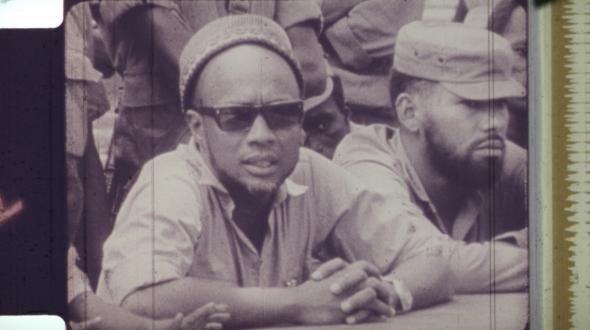

Sana na N'hada at the Campada Base, September 1973.

Sana na N'hada at the Campada Base, September 1973.

FILMING AMÍLCAR CABRAL

At that time, you filmed the portrait exhibition of PAIGC’s struggle with Amílcar Cabral

In September we already had 16mm cameras, the Beaulieu R16. So, we filmed for the first time. 1972 marked the ninth year of the Guinea-Bissau Guerrilla and we filmed an exhibition inaugurated by Amílcar Cabral, who presented it to Sékou Touré, in the presence of the diplomatic corps accredited to Guinea Conakry and the PAIGC militants who were there. So, it was my first time, and I happened to film Amílcar. I did the image and Flora Gomes did the sound. It wasn’t a decision; I took the camera and Flora took the tape recorder. We took advantage of the lighting on Guinea Conakry television, which had an operator with a lamp. We pushed each other to get the images.

What was the exhibition like?

Photographs, portraits of the fight. The weaponry seized from the enemy, the cadres formed, photographs of mutilated people, hospital patients, the war equipment and the enemy.

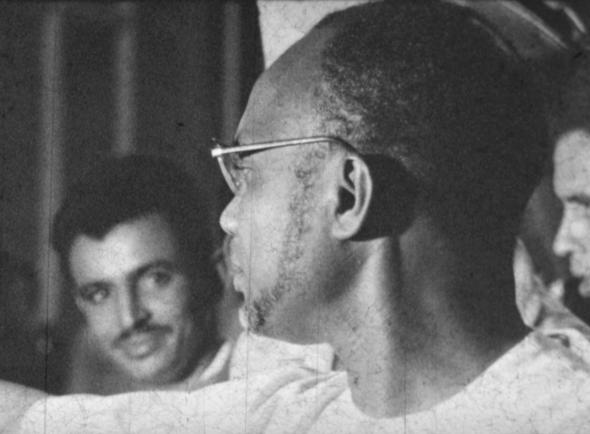

Cabral at the Semana da Informação (Information Week) exhibition, Conakry, 1972

Cabral at the Semana da Informação (Information Week) exhibition, Conakry, 1972

Was the aim to publicize the PAIGC’s progress?

Precisely, it was a kind of balance sheet of nine years of the PAIGC’s struggle. So I filmed it, and as I said, I didn’t have a light bulb, I had to take advantage of the light framing. It wasn’t great, when I wanted to do a close-up, the TV operator in Conakry pulled me away, and when I went back to film the close-up, they switched off the light, and it became impossible.

You don’t have any close-up shots of Amílcar?

When he was presenting the exhibition in his office, yes, but when he was giving a speech in the exhibition alone, I wanted to film but it wasn’t possible. I was close but I couldn’t, the cameraman and the sound man took up everything. We were downstairs, so I lacked that feeling of being closer to my audience. But Miriam Makeba and Sékou Touré still appeared. Before that, Amílcar had given a press conference, and there I had the chance to film him up close, but there were also many journalists watching in front of him. It was the first time we filmed him. It’s very important, I think we can make something of these images.

How do you relate that experience, the embryo of an entire career, to now being here to inaugurate a project you’ve always wanted to do: a media library and a book library?

It’s the result of my conclusion: certain things can’t be achieved through official channels. Not because people are bad or because they don’t care, I recognize that they have other priorities: agriculture, health, transport. We’ve tried several times to create funds with state aid, private aid, to produce films, but it didn’t happen. Since the law creating the National Film Institute was passed in 1978, there has never been the slightest attempt to create conditions for making movies, but there has always been film and money to spend on reporting political speeches. I oversaw the National Film Institute for twenty-two years, and no minister accepted or listened to my proposals, all kinds of imaginings I made didn’t come to fruition.

What was it like to film during the war?

Towards the end of the war, I was a reporter on the northern and eastern fronts. That meant walking to Senegal for almost a week, recharging my batteries, resting for three days and going back to the bush. Once my battery was charged, I could film anything, any attack or any bombing on the way. The Geba River is there, it’s the boundary between the eastern and northern fronts. My area of intervention was from Bafatá to here.

A huge area.

On the east front, someone (Paulo Correia) wanted me to do the same thing as on the north front. So sometimes when I went back every three months to take the already exposed film and to pick up the virgin film, I would stay on the eastern front. I would film what there was to film, then go back to Conakry to get more film for the northern front. It was walking and walking.

The working conditions were very tough indeed.

The most important thing in guerrilla warfare, our warfare here, is to walk, always. You always have to walk.

But were you accompanied?

Of course. While I was in the liberated area, when there was no fighting nor shooting, I didn’t need protection. When people had guns to shoot at aircraft, the pilots were more cautious and I would film, but if there was an ambush or an attack, the bosses of course wanted me to because they wanted to immortalize themselves. But sometimes, if the base said, “We’re going to attack ten kilometers away,” that was fine. But I began to realize that we were already close to the objective through our behavior, the smiles were more nervous, people started pulling out their caps, their Kalashnikovs, that meant we were close. Then we were no longer friends. They didn’t smile at me anymore; they didn’t want me around. At first, back at base, they wanted me to be close to them, but after that they didn’t.

You had to think carefully about what and how to film.

I had to film the space, the footsteps, especially the faces and the movement; but I couldn’t film too much either, because there was little film and I had to carry a heavy briefcase with the material.

What about the logistics of eating and staying hydrated daily?

To save water, you cut up a lemon and put it in a liter of water. Then the water doesn’t taste so good, it’s strong, and the lemon makes you less thirsty. With this, a liter of water will last you about three days.

And how did you manage to get food?

When it appeared.

Did the people in the tabancas help out?

Yes, whenever they could. In the first few years, 1963 to ‘65, there were a lot of reserves, a lot of food and a lot of cattle. Then the Portuguese troops ate, we ate too, and eventually there were no more domestic cattle, goats, pigs. The next victims were antelopes, wild birds, gazelles, hippos, you name it.

And crocodile? I’ve tried crocodile meat and it’s not bad.

There’s no fat in it at all. An iguana, for example, is healthy.

You did this documentation and handed over the material, then the films were passed underground?

No, nobody saw them. We were filming for five years, until 1976, and it was only later that we saw some of the images.

So who kept the films?

The PAIGC received them and sent them to a friendly country if there was a delegation. To Sweden, the Soviet Union, Algeria. Their intention was to develop the film and send it back.

And after that?

The only one that sent it back was the Soviet Union. But they sent the negative, they didn’t make a copy of the work. It was what we filmed at the Proclamation of Independence in Boé on September 24, 1973. Since 1974, I still haven’t been able to find out the whereabouts of the other films.

What a relief to have saved the footage of the self-proclamation of independence. And when did you see them?

In September 1974 (after the April 25 revolution) I was in Conakry where I took my exposed film, and I found the one with the proclamation of independence on a shelf. As there was a boat going to Bissau, people started preparing PAIGC things to send there. I packed up everything related to my work and put it on a boat. I took the boat to Boké, got off and went back to Conakry. As soon as I arrived, they told me: “You have to go to Bissau, there’s a mission to Cape Verde. The Portuguese plane will take you from Bissau to Cape Verde.” So I went from Conakry to Bissau on a Portuguese army plane. I didn’t even know Bissau yet, there were still Portuguese troops there, there had been a spontaneous ceasefire, it hadn’t been decreed. We were already starting to negotiate. I remember that on September 9th, six thousand troops embarked in Bissau to return to Portugal. And there I went on the plane with the PAIGC delegation from Guinea-Bissau to Cape Verde on the 12th, led by Pedro Pires, with Julinho Carvalho, Agnelo Dantas, Silvino da Luz, etc. Cape Verde was still Portuguese, like Bissau. The PAIGC hadn’t arrived yet, it wouldn’t arrive until October. But it wasn’t until 1975, when I once went to accompany Swedish filmmaker Lennart Malmer, who had things in customs at the port of Bissau, that I discovered the material I had packed in Conakry a year earlier. It had been in the sun all that time.

And how did you manage to develop more material?

In 1976 we made a stand with Mário Pinto de Andrade [general coordinator of the National Council of Culture and Minister of Information and Culture of Guinea Bissau between 1976 and 1980] and his wife, the director Sarah Maldoror, to raise awareness and get Swedish funding to reveal what was still in Conakry from what we had filmed five years earlier. But that was only part of it.

Because a lot of material has been sent for development and will be somewhere?

Even so, we had a hundred hours of footage. What wasn’t sent to the friendly countries was there, in high temperatures and all tangled up. We almost always shot on Kodak film, in black and white. I went to Sweden to check the condition of the developed images, which, surprisingly, were in good shape. I was only able to put together a first film called The Return of Amílcar Cabral.

Sana na N'hada and Flora Gomes, Malafo 2022. Photo by Marta Lança

Sana na N'hada and Flora Gomes, Malafo 2022. Photo by Marta Lança

THE DEATH OF CABRAL

In The Return of Amílcar Cabral, are the images only made by you?

18 of the 19 reels are mine; the other is Flora Gomes’. Me and José Bolama Cobumba, who did the sound for the film, went to Conakry with the delegation that brought Amílcar Cabral’s remains. Flora Gomes filmed a reel at Bissau airport, when the body arrived, we had two cameras. The film’s story is about the transfer of Cabral’s body from Conakry to Bissau. I followed the whole process from Conakry to the airport, to the Palace, to get to Fort São José da Amura, where he was buried.

What were your contacts with Amílcar Cabral like?

The first time I saw him was in Morés, on the northern front, in mid-1966. Then it was in Conakry, Havana and again in Conakry when I returned from Cuba. On December 22, 1972, in Dakar, I saw Amílcar Cabral for the last time, a month before he was assassinated. When our group of four was in Dakar on an internship at the Actualités Sénégalaises, Amílcar Cabral came to visit the PAIGC Home. At the end of his visit, he called us aside to give us a mission: to go and film, on the three fronts of the struggle, the preparations for the proclamation of the State of Guinea-Bissau. At the end of this visit, Amílcar Cabral arranged for us to meet in Conakry in March of the following year to take stock of our visit, which was followed by: this is a secret, don’t tell anyone!

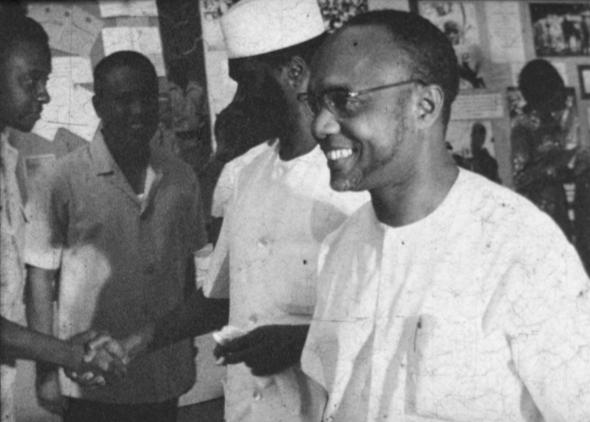

The Return of Amílcar Cabral, 1974, photograph

The Return of Amílcar Cabral, 1974, photograph The Return of Amílcar Cabral, 1974, photograph

The Return of Amílcar Cabral, 1974, photograph

And how did the mission go?

A few days later, I, Josefina Lopes Crato, José Bolama Cobumba and Florentino Flora Gomes rode in a Soviet Jeep Waz, driven by Sirifo Dansó, inside which we met a Caucasian man that none of us had seen before, which plunged us into a deep silence that nobody broke until we reached our destination. We later learned that the man’s name was Oleg Ignátiev, a reporter for Pravda. We set off for Ziguinchor, Casamance, in the south of Senegal, where we arrived at around 8pm. There we were met by Lúcio Soares, military chief of the northern front, Luís Correia, from the front’s security, Manecas Santos, from the heavy artillery, Duke Djassy, from the army corps commanded by Quecuta Mané, Cambanó Mané, alias Iongoiá, from the army corps commanded by Braima Bangura. They lodged us at the residence of Luís Cabral, then head of the northern front. Nobody said a word all afternoon. At night, in view of the security requirements, our usual jokes were whispered, we talked about what could happen to any of us and left messages for our respective mothers, whom none of us knew. The jokes were more a derivative of the nervousness and anxiety about the overwhelming responsibility that Amílcar Cabral had placed on us. What if, by some chance, precisely out of fear of not failing, we failed the mission? That was the question!

We spent the night together in a room; Oleg Ignatiev occupied the bedroom. The next morning Luís Correia and Duke Djassy came to remind us that, in addition to the ban on speaking aloud, we shouldn’t stick our noses out of the house either. In response to our protests, we got permission from them to go and stretch our legs and took the opportunity to dive as far as possible into the grassy plains of Ziguinchor, returning soon to our confinement. My friend Cambanó took the opportunity to make fun of my supposed ‘prison’.

In the late afternoon we set off towards our northern border, some 100 kilometers away.

We didn’t stop at Cumbanghor, heading straight for Sambuia. From there we crossed the Farim River and passed through Djacal to spend the night in Maquê. This route is known to me as I passed through the last tabanca six years ago, back in Morés after having taken nine wounded people to the Senegalese border, victims of the bombing that took the life of my boss Simão Mendes on February 19, 1966.

In the meantime, did you realize who was the White man that was with you?

The identity of our guest only became clear to us when our team was introduced in the Maquê base: “He is Mr. Oleg Ignátiev, a special commentator for Pravda, a famous Soviet newspaper.” Then we distributed the roles within the team. We all had a camera, including Oleg, and each of us was allowed to use our own. The two members of the team who hadn’t filmed before were now in charge: José Bolama Cobumba and Josefina Lopes Crato. The two of them would take turns due to the fatigue from the march. I was left with the responsibility of interpreting everything said in Creole to Spanish for Oleg.

You took on the important task of interpreting for the Soviet.

My colleagues decided that I would be a good interpreter for him, Oleg, since he had entrusted me with his documents when he left for a rally. I also had to take care of his logistics, security and related documents, which couldn’t fall into someone else’s hands.

From Maquê, the military chief of the front, Lúcio Soares, decided to always attack the garrisons that were on our route. In Maquê there was a first meeting, which José Bolama filmed and where Oleg was introduced to the public, which was a kind of invitation from the Tuga wolf to the PAIGC corral. He spoke, which led to the need to interpret his words.

And then?

The following night we left Maquê for Morés, through Madina, under the rumble of bazookas and recoilless cannons, in their respective attacks on Olossato and Mansabá, who had to be forced to retreat to their shelters so we could pass through peacefully. We spent the night in Madina to set off the next morning for Morés.

In Morés, I went to fetch some water for Oleg, my guest, to bathe in. Here I met up with my old colleagues from my internship, most of them girls, who believed I was already a doctor, which I insisted on disproving to no avail.

Our outpourings didn’t last long, because when I returned to the hut of my guest, Oleg Ignatiev, I found him lying on his back, inert, unconscious, his eyes bulging, with a radio set on his chest. From the radio, which was whistling more than talking, I recognized the voice of President Sékou Touré in an energetic tone, but whose meaning I couldn’t understand, with my meager French and the panic that Oleg’s condition inspired in me. I woke Oleg up, who mumbled something in his own language that I didn’t understand and fainted again. Then I ran to see Lúcio Soares and the political leader of the northern front, Pascoal Alves, and I found both clutching another radio and listening to the same president of Guinea-Conakry, Ahmed Sékou Touré, but this time I realized that it was something very serious. It had to do with Amílcar Cabral. But I was chased out of there, without regards, by the two PAIGC leaders.

The Return of Amílcar Cabral, 1974, photograph

The Return of Amílcar Cabral, 1974, photograph

THE FATAL NEWS

How did you hear about Amílcar Cabral’s death?

Back with Oleg, this time I found him awake and more serene. The first thing he said to me was a terrible question, which I could hardly answer, because it was so immense, surprising, terrible, overwhelming. Oleg Ignatiev said: “They killed Amílcar Cabral, what are you going to do? Will the PAIGC end, will the fascists win?!” Without letting me try to answer, in case I figured out or managed to stammer out a sentence, Oleg demanded that I take him to the leaders of the northern front, and off we went at a breakneck pace. This time the interested parties couldn’t chase me away. Oleg repeated the same question, but this time to the right people, and didn’t get an immediate answer, or perhaps I hadn’t heard correctly. He said: “I have to get to Conakry before…the funeral of…” Pascoal Alves made an imperative gesture to get me away from there, and I was literally running away when the group that attacked Mansabá the night before arrived and Lúcio, as if moved by some kind of spring, stood up and gave an order in an energetic voice that I had never heard before, ordering the combatants, led by Mbemba Seidi and César Mendonça, to return immediately and attack Mansabá again by dawn. The latter, incredulous, were about to protest when a gesture from Lúcio towards the radio let them hear the fatal news. The next day, at a rally organized in Iracunda, the old Quebá Irá, the one who used to call me Little Nurse, summed up in one sentence what Oleg Ignátiev wanted to know. Quebá Irá said: “But who says that Amílcar Cabral is dead? Even if that’s the case, he’s already unblocked the road to independence, the task left to us is to pave it!”

Did you decide to film Cabral’s funeral?

Oleg came back from the rally in high spirits. Our team’s mission, which was to visit the three fronts of the struggle, was now compromised by the disappearance of our leader, Amílcar Cabral. But Oleg Ignatiev had another unsolvable problem: the quickest way to Conakry was through Senegal, and since he had just officially left Senegal, he could no longer re-enter without a visa. The solution imposed on the group was thus to continue our journey across the country and reach the southern border, where none of us needed a visa to enter. Would we make it in time to attend Cabral’s obsequies?

Did you make it?

The next day, we crossed the Mansoa/Mansabá road to spend the night in Mandincara/Darsalaam. Our arrival coincided with Titina Sylla’s, who oversaw health services on the northern front, and was accompanied there by her faithful friend, Ana-Maria Gomes, political commissar for the Sará sector. Titina, in the opposite direction to us, was going to Amílcar Cabral’s funeral in Conakry where she would never arrive, having been ambushed by a Tuga patrol. She died in the Farim River, at the Djacal/Sambuia crossing, which we passed just a few days before to Maquê. But before we parted, the next morning, after taking some photos with Titina and Ana-Maria, the latter returned with us to Sará, with her companion Lúcio Soares.

At the Sará/Enxalé base, our team stopped for a day to organize our crossing of the Geba River. On a quiet afternoon in January 1973, we passed through Malafo, exactly where we are and where our Media Library is located, to the eastern front in what is known as “Zone 7.” We crossed the Geba River through Enxalé, my home tabanca, in a canoe rowed by Fóna na Mbitna, who is my age.

In the midst of all this sadness, you return to your childhood places.

We almost bumped into a speedboat that was patrolling the river, with a silent engine, upstream. I was describing the place to Oleg Ignatiev in a broken voice, with that excitement of passing by where I had been as a child, when Fóna warned me, cussing about the speedboat that our pirogue was going to bump into in the opposite direction, bound for Ponta Varela. We just barely escaped! I spent a long time staring at that spotlight on the speedboat, which was moving away, and thinking about what would happen if we were caught, with Oleg on board, while our canoe was moving very slowly as we were going against the current. As soon as we set foot on the muddy ground of Ponta Varela, Caetano Semedo’s men attacked Xime’s barracks. The tugas didn’t take long to respond and some cannon shells from the Xime battalion came to welcome us to Zone 7, forcing us to fall flat on our faces in the mud. After passing through the outskirts of Xime, we stumbled across our comrades, the perpetrators of the previous night’s attack, who were returning to base. Even Caetano Semedo and Ansumane Mané, alias Bric-brac, his deputy, acted as guides. So well, in fact, that Caetano Semedo and I were discreetly catching up after missing each other for almost seven years, after he left for the Military Academy in Nanjing, China, and left me in Bumal to open my own school.

Sana na N'hada at DocsKingdom, 2017

Sana na N'hada at DocsKingdom, 2017

Your ability to remember accurately is impressive…

From now on, weakened by the forced march and the lack of food, I don’t have much memory of the events. All I know is that Oleg barely accepted the little food that appeared. We left Zone 7 for Gbotchol, Quinara, where we only had a short break before continuing to Unal at 4am. That afternoon we crossed the Buba/Quebo road and arrived at our destination at 7pm local time. On the way, we had to take a break between 10 am and 4 pm because Oleg couldn’t stand the torrid heat and very humid weather, and he was as weak as the rest of us. Oleg was only taking a few pills, “to mitigate the effects of hunger,” he told me.

At Unal we arrived at an abandoned base. Our escort didn’t know where the comrades had moved to. Oleg asked me to check how long it would take to find the new base. Nobody knew. Oleg insisted, I had to repeat the question. The man said he didn’t know and continued: “the new base could be far away or not far away.” Oleg lost his temper. How can a place be far and not far at the same time? Are you kidding me?! I am the representative of a great country that helps you fight for your freedom… The man didn’t understand, but he knew that my guest was furious. The escort made a decision, he fired a long burst of Kaláshnicov into the air, which only infuriated Oleg even more. He went into a long tirade saying that we were wasting bullets that cost a lot to produce. I didn’t translate anymore because I thought it was pointless. Everyone looked at each other defiantly. In the distance, in response to our escort’s gunfire, a replica of tracer bullets arrived in the air. We knew where to go.

It was the code signal.

At the Unal base, I finally got to meet comrades Úmaro Djalló, Abubacar Barry and Iafai Camará, whom Caetano Semedo always spoke to me about, as some of those who were leading our struggle. From Unal we traveled by canoe all night, for about nine hours, until we reached Candjafra at dawn. While still in the canoe, I was woken up by shots from Guiledje’s cannon, which was trying to hit the truck that was picking us up at the landing.

After a 15-day journey, we managed to cross the whole of Guinea, from Sambuia, near Bigene, to Candjafra. João da Silva, the local official, welcomed us without even giving us time to introduce ourselves. Apparently, he was expecting us, because he told us that we had to cross the small river/border before dawn, as the Tuga planes were about to start their daily bombing raids without delay, and they did as soon as we left the raft, which was almost destroyed. But we were already in the Republic of Guinea.

Was it difficult to deal with the assassination of a great leader?

The reality of Amílcar Cabral’s death began to invade my consciousness, surreptitiously and insidiously. The idea of killing comrade Cabral seemed surreal to me. I absurdly refused to believe that idea, but the incessant fighting everywhere brought me back to reality: the combatant’s anger at the death of his chief was expressed.

In Conakry, at the PAIGC General Secretariat, as soon as we arrived, our team of four filmmakers had a meeting with Amilcar Cabral’s widow, comrade Ana-Maria.

What were you able to find out about those tragic moments at the time?

She described to us the last journey she made with her husband before they returned home at night. The car they were traveling in was still at the scene of the tragedy, with a bullet hole in one of the doors. The brownish stain of Cabral’s blood stained the ground. Ana Maria told us that Amílcar Cabral absolutely refused to be tied up, with his hands on his back, and even more so to be taken to Bissau, as his murderers wanted. On the contrary, Amílcar Cabral vehemently insisted that they come with him to his office for a serious conversation. That even after he had been shot the first time, he still wanted to know what was going on and why.

I listened to it all en état second, as if I were dreaming, delirious. Now the world seemed to be collapsing on my head.

Then we went to see comrade Aristides Pereira, who still bore the signs of the ropes he had been tied with in his elbows. Fortunately, he was rescued before they arrived in Bissau with him tied up, as the kidnappers had intended.

I no longer remember what happened to me that day, nor do I know how I got to Dakar. All I know is that, while still in Conakry, I declined the invitation to attend the trial of Amílcar Cabral’s murderers.

MEETING CHRIS MARKER AND SARAH MALDOROR

And how did you show the images of the struggle to the Guineans?

As part of the PAIGC’s 20th anniversary (1976), we got funding to get 16mm cameras, a moviola (a Steenbeck editing table), and a machine to re-sample the sound from 9 to 16mm. We got a Nagra IV-S recorder. Sweden financed the development of our film, the print run and the equipment. Then I borrowed a truck, and we were able to do traveling cinema.

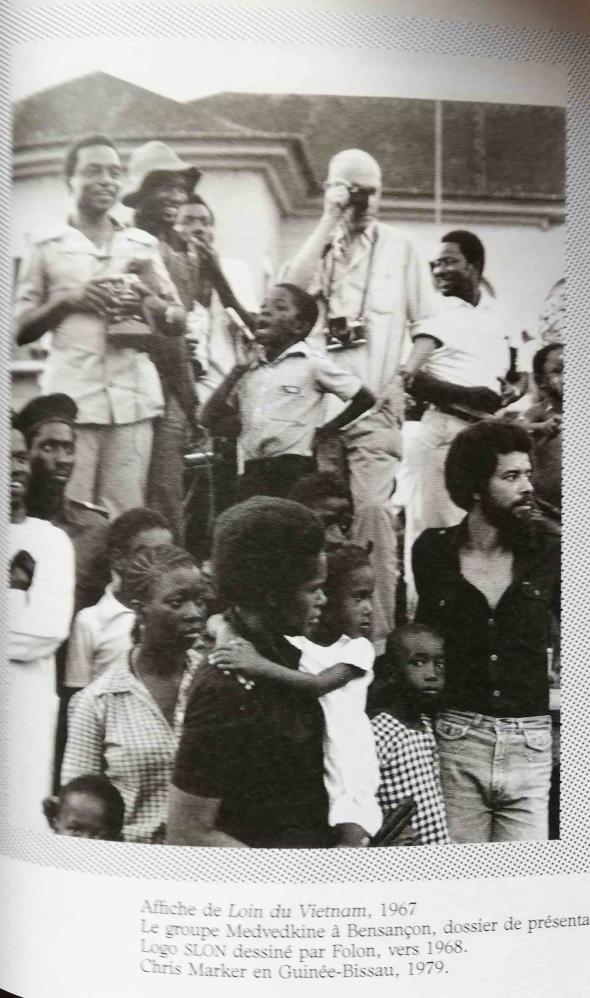

Chris Marker even gave us a 16mm projector and many films, both his and Soviet ones (by Dziga Vertov and others I can’t remember). We went around the country projecting some of the things we filmed and that foreigners also made during the conflict: Cubans, Englishmen, Swedes, Finns, etc. That’s when I met Chris Marker, who came to Guinea with Sarah Maldoror in 1979. He and I walked around a lot.

At that time Sarah Maldoror released the film À Bissau, le Carnaval.

I was her assistant, I was with her on that movie just after independence, and also on one of Sarah’s movies in Cape Verde (Fogo, Fire Island, 1979). I even replaced her once, because she wasn’t feeling well, when we climbed the Pico do Fogo. Her technicians accepted my direction when filming the volcano, which, luckily, wasn’t active.

Sana and Sarah Maldoror. Camdjambary Base, handing over the OAU Ambassadors' Credentials to President Luís Cabral.

Sana and Sarah Maldoror. Camdjambary Base, handing over the OAU Ambassadors' Credentials to President Luís Cabral.

Chris Marker played an essential role in your life.

He came with Sarah and I had to transport her technical team: Sarah herself, the cameraman and the sound engineer, to Cassacá, in the south. We went by helicopter. I took the team to the airport and went back to the hotel to pick up Chris, to accompany him to the helicopter to follow Sarah. It was the next flight, but there was only one seat on the helicopter. I wanted Chris to go, but he didn’t want to go without me, and I didn’t want to go without him, so we stayed. Sara went and filmed the graduation of the military who were in position in Cassacá. That’s how I took Chris Maker back to his hotel, but his room already had a new occupant and there was no other chance of finding accommodation for my guest.

We still went to my house, where I offered him housing until Sarah returned from Cassacá. I introduced him to my wife and son; he accepted dinner but declined my housing offer, telling me “Let’s go to your work.” And so he began to teach me the editing technique on our Steenbeck moviola.

How did that editing exercise go?

I had classified the images we had, some things were well distinguished, everything was written down, classified on paper. My colleagues and I made a first movie about women, about Titina Sylla. Chris Marker taught me the editing tricks.

On the first of the lesson’s three continuous days, at 3am, I was dead tired, and Chris wasn’t, so I proposed a break, but he didn’t even want to hear my case, he would never sleep! I was very lucky and, by way of a thank you, I told Chris that I already knew how not to film.

At the time I had a lot of film; the people who came here to film would leave one or two reels and I would put everything in the cooler, because I wanted to make a movie about artisanal fishing, following the fishermen in their fragile canoes at night. There was film but the brands and batches were very mixed, they were badly preserved, and I wanted to make sure that the film was really worth something. So I asked Chris to take some reels for testing, just to see if the film was still any good. Fortunately, it was fine and the images I shot served Chris in his movie A Grin Without a Cat.

There are things that can be solved straight away on the shooting. He did it spontaneously, it didn’t come with the mission, was it a sympathy thing?

At first, I didn’t see how big Chris Marker was, only after did I realize the true scale of the man. He came with Sarah, and the odd situation we found ourselves in forced us into a certain intimacy.

Sana na N'hada and Chris Marker in Guinea in 1979

Sana na N'hada and Chris Marker in Guinea in 1979

Did you already speak a little French because of Conakry?

I learned French in Bissau because Mário Andrade had an advisor, Sérgio Michel, with whom I spent a long time preparing the statutes of the Film Institute, and then we would discuss them with Mário Pinto de Andrade, and even with President Luís Cabral. Then it was sent to Francisco Mendes’ government to be promulgated. I spent a lot of time with Sérgio Michel. I read the classics in French, like Victor Hugo and Rabelais; I knew some of them from Cuba. Well, I learned to talk to people. And I’d learned some English at the lyceum. In Senegal too. But there our internship was in Creole interpreted by a Cape Verdean descendant who was there, Orlando Lopes, who spoke Creole. We communicated very little in Senegal because we were very isolated. At Actualités Senegalaises we couldn’t do much work because there was no budget. We were given tasks to do that we had already seen in Cuba. The internship was interpreted from French into Creole. It wasn’t very instructive, but we always learned something.

THE NATIONAL FILM INSTITUTE AND ITS FILMOGRAPHY

And did you gather any material at the National Institute of Cinema and Audiovisual of Guinea-Bissau?

We started archiving the films that were disorganized, but there was never any consistent support to make a good archive. But we knew the content of each reel, big or small, we had written it down on paper. And we were making other movies, for example Guiné Bissau seis anos depois, a kind of assessment of what the country’s government was doing during the first six years after independence. There was the sugar factory, the plastic factory, the oxygen factory, the construction of a new lyceum that is now the Universidade Amílcar Cabral (Amílcar Cabral University), the cashew juice factory in Bolama, all of that existed.

Does that movie exist?

We were finishing the movie when Nino Vieira’s coup d’état took place (November 1980). I spent a good part of that year in Catió, in Bafatá and in the bush, filming. I went back to Bissau to present to the Minister of Information and President Luís Cabral what could be made into a 52-minute movie, according to my impression. We were going to hold this meeting on the very day of the coup d’état. I kept the film. But as our Nagra had issues because it had been rained on and battered, it needed to be repaired. There was an invitation from Mário P. Andrade to go to Paris for a conference of what is now the International Organization of La Francophonie, and as he was no longer in the country and his successor wasn’t interested in traveling at that time, I used the ticket and took the film we had shot and the Nagra for repair. I left it there to be developed, and today we have that material, it was lucky, but it wasn’t possible to make the movie because there was no budget anymore.

There were many difficulties in making your films, but you managed to do many things as an employee of the Institute.

There was always money to report on politics. To accompany President Luís Cabral, or Nino Vieira, there was money for all that. It was called for and as employees of the Institute we had to do it, of course. Even so, I made The Return of Amílcar Cabral (1976), which is a state production. In 1979 I made Os Dias de Anconó (The Days of Anconó), for the 1979 International Year of the Child, with the help of Sérgio Michel, and we got funding from UNICEF. In 1984, with the film reels I collected here and there, I made the film Fanado, I filmed the Balanta Fanado, which is a bit more spectacular, with songs, from north to south, in seven different villages. In 2004 I made the film A nossa Guiné (Our Guinea), about the state of transportation and social and economic degradation. I filmed a huge ox being lifted onto a cargo boat by hand in the south.

The Herculean effort to lift the country…

Indeed! The film was financed by the French Cultural Center, I asked them to get me a canoe to follow the boat with women and children on their backs, who had to climb onto a huge boat by a rope ladder, like paratroopers. One woman went up with her daughter, another with a goat and a pig. The boat goes to Cacine and back. I was told “no, that’s too expensive, we can’t afford it.” Well, I went by land, got on the boat that goes from Catió to Cabochangue; I went around and waited for the next boat at the port of Cachil. The movie was broadcast on TV France 5. It was banned here, like some of my other films. In 2005 Luís Correia, from Lx Filmes, said that there was a grant for making a documentary in each PALOP country. The deadline was short, but I made Bissau d’Isabel, which follows the economic difficulties of Guinea-Bissau.

And you collaborated with other directors.

With Sarah Maldoror, and from the 1980s to the 1990s, I worked for a 10-minute program on Swedish television, Antena 2, with Leila Assaf-Tengroth. With her, we filmed West Africa with different themes, toxic waste, agricultural projects. On the Senegal-Mali border, I went to the FESPACO film festival in Ouagadougou as a guest and as a reporter for Swedish television; I did another on the locust plague in Senegal. In short, we had ten minutes on television to talk about West Africa. I also assisted her on two feature films on social issues here in Bissau. So I worked as an assistant director and producer. In 1987, Flora Gomes made his first feature film, Mortu Nega, and I was assistant director and production director. All without any money: the film had no budget of its own, nobody was paid here.

How can you make such a movie happen without money?

We filmed in the forest very close to here. I’d go to Bissau at ten o’clock at night and order chicken, rice, oil, things like that, to eat. I’d leave it there, they’d type them up, deliver them, then the next night I’d go to sign for them, and they’d type again and leave them there. I’d leave here at 11 o’clock at night and sign for what I’d left the previous nights and find out whether or not they’d gotten what I’d asked the companies to give them: food, fuel, vehicles. I asked the military for a helicopter flight to simulate a helicopter attack. The CEMFA was friendly, helping the production a lot.

It had to be someone like you who knew the terrain well.

Yes, I also knew the type of ammunition, the caliber, there were a lot of 120 mm rockets from the struggle, you can keep that for a while.

So it’s a miracle, the movie Motu Negra?

Yes, and a lot of commitment from the director. The budget was only enough for the technicians, and they took the opportunity to put the equipment as part of the contract. So the government paid for it, that’s all. One day they were filming and the pilots started doing a military maneuver with jet planes. The sound engineer, Pierre Donnadieu, said to me, “shut that thing up” and I thought, “but I can’t give orders to the military.” Well, I went there and it turns out I know their boss, I asked him to “do the flights a little further away, half an hour later come back here.” I told the director of photography that I could film, but only for 30 minutes.

Later, INCA became very neglected. I remember going there in 2010 when Carlos Vaz was in charge and all the equipment was abandoned, left to the rain and the flies.

That was the result of someone (a Secretary of State for Culture and Sports, a history graduate, even, whom the PAIGC sent to study in Russia) saying that he needed our little space, our editing room, to set up a news agency. So we had to take all the film out. But to where? We had to move our archive from where it was and he left everything in the atrium, the material spent the dry season with dust and the rain got everything wet. In short, we lost 60% of what we had as an archive. It was a disaster; it almost drove me to suicide. The only thing the INCA did was pay for fuel and salaries, we were earning like servants.

Destroying an archive that had been partly saved with so much difficulty.

At that point I was a bit crazy, I couldn’t sleep, I drank a lot of coffee, then I’d go to the French Cultural Center to read something, I was desperate.

But you realized how it could be done differently.

During Chris Marker’s various trips here, he sent Anita Fernandez to teach us how to really edit films. So at the end of this internship, we wrote a script together and she made a movie called Le Balcon, with Flora on camera and me as sound operator. Chris started talking to me about something private because he has a production in France, so I went to talk to him. Once, when I was coming from Sweden, I passed through Paris in ‘84 and showed him my movie Fanado to see. He started telling me that, instead of a state thing that gets us nowhere, we should think about things like this. The result of this is the letter about the video library that Filipa César had woven as a panu-de-penti. We talked a lot, Chris and I; I took him to Bafatá, the native home of Amílcar Cabral, to the fort of Cacheu, where the toppled statues of Portuguese heroes that had been taken there were. I filmed the fallen statues of colonialism that I discovered in Bissau, before they were taken to Cacheu.

THE TOPPLED STATUES OF COLONIALISM AND THE BIRTH OF THE COUNTRY

Have you ever used these images in a movie?

I’m going to use it now in this movie. I have another idea for the birth of this country, Flora and I filmed the Proclamation of Statehood (in this report I only filmed short portraits of the deputies and guests, because I had battery problems), it’s been fifty years since then, Amílcar Cabral’s centenary. But I have to finish the feature film I’m making. I think we can do a lot with these images. In Bissau, there was a mattress foam factory near my house. I went there while I was waiting to buy a foam mattress. By pure chance I saw some things, statues of Teixeira Pinto, Nuno Tristão. They were there abandoned to their fate, in Bafatá they had torn everything down. I went to get the camera and filmed the place as is, with grass growing on top. Then I had the idea of filming all that in the port of Chim, of Bafatá, of Bissau, in the navy barracks in Bissau, I filmed everything. That’s when the idea of Guiné Bissau seis anos depois came up. I wanted to make a movie out of it, how this country was born.

Lennart Maalmer. Madina Boe. Proclamation of Statehood. photo by Bruna Amico (Italy) or Ingela Romare (Sweden)

Lennart Maalmer. Madina Boe. Proclamation of Statehood. photo by Bruna Amico (Italy) or Ingela Romare (Sweden)

And how it needs to mature.

I’m already addressing that in this movie I’m putting together. The movie is called Nome e Tótala. The gist of the idea is what it cost us to create this country and what we’re doing with it. I’m gonna get beaten up. In Creole we say that “a dry fish is not afraid of hot water,” so…

COLLABORATION WITH FILIPA CÉSAR AND THE ABOTCHA MEDIA LIBRARY

Since 2011, Filipa César has helped rehabilitate the archive with support from Germany. What has your collaboration been like?

I often say that the appearance of Filipa César in Bissau was a kind of miracle for our archive; for me Filipa was an incredible opportunity. We’ve been promoting our archive images in Europe, the Americas, Guinea-Bissau and even Egypt. Filipa used them to make a documentary with commentary for the young by Flora Gomes and myself.

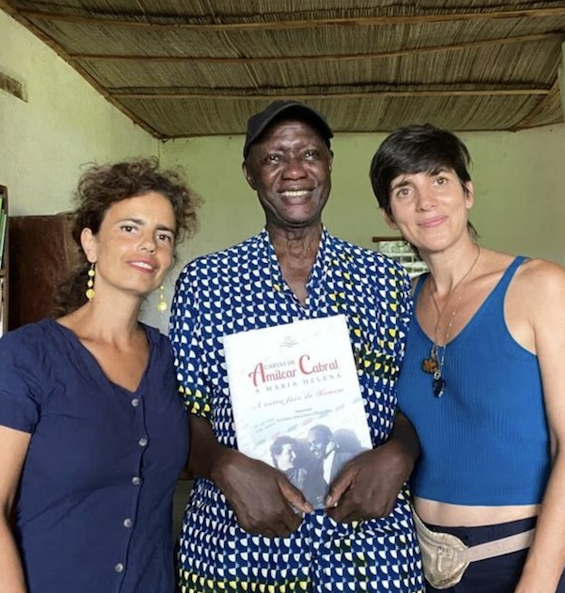

Marta Lança, Sana na N'hada and Filipa César

Marta Lança, Sana na N'hada and Filipa César

We opened the Abotcha Media Library in a Balanta community in Malafo, which you know very well. What are your ambitions and concerns about its operation?

If there are events here like a big avalanche, I’m afraid it will be submerged. I want us to be able to digest all this well; let it serve as information for the community. Let there also be nationals who come from outside the region. Let them remember all that they can value; the nature here, the economic, agricultural and ecological potential. We have to value it. For example, we did a workshop on bees. It was related to how they reacted. People kill the bees with fire to get honey. Because they’re treated like that, the bees have become very furious, very aggressive.

In Germany the fine is high if you kill a bee, it’s a crime.

Of course, we’re endangering ourselves. Without that, there’s no agriculture. But I want them to digest everything little by little, let’s not speed things up too much. Because they also have things to teach us.

What are the Media Library’s strengths?

The Media Library, about the film part, it’s not only me, but Filipa, Flora, Suleiman, other people who are on television are going to have to commit to making short films that don’t involve a lot of budget. Things can always be done from here, you can do a lot here about agriculture. Right now I want to make a movie about how rice came to be the staple food in Guinea Bissau. I want to make short things that provoke a reaction. How did this become possible because these Balanta people don’t usually migrate, if they do it’s because they’re looking for a flood plain. If they migrate, it’s because they’ve discovered a bolanha. A strong community has migrated north and south.

THE BALANTA’S COMMUNITY CULTURE

Are the bolanhas (rice paddies) here under threat?

It’s because the usual thing is to conquer the mangrove to make the bolanha. But things are difficult because the dikes aren’t well made… The dike has to be made in the dry season, when the mud is still soft. When the soil is still soft, the clay sticks together, you hit it a lot with the plow, then it dries out and holds up when it starts to rain. Then the dike has its enemy, the crab, which pierces it. When there’s high tides and the water level rises, these holes left by the crabs cause the dikes to collapse. Here, people are very fond of nature, but on the island of Bubaque they are still much more ecologist than the rest. They respect nature a lot. They’re very good at ecology. It’s inborn in them. And the Bijagós have a different society to ours, it’s hierarchical and everyone says and does what they have to do, the roles are well distributed. And it’s the woman who decides who she wants to marry, who takes the initiative and if she doesn’t feel comfortable, she finds something else and moves elsewhere. And they’re very strong. They have a very strong structure, very hierarchical, very closed. Here the Balanta woman, compared to other ethnic groups, is also much freer, similar to the Bijagós, but here the work is partitioned. Cutting down trees, climbing trees, going fishing - that’s a man’s job. It’s his job to plow the soil in the bolanha to make the seedbed. Both here and there. Yes, it’s a man’s job to make a farm. It’s the woman who uproots the plants and transplants them into the bolanha, but if the man has finished the seedbed, he helps the woman.

What are women’s other roles?

A woman does a lot, she never rests. She has to make the food, she has to hull and pound the rice. In all ethnic groups, the pestle belongs to the woman. Men don’t do that. It’s the woman’s kitchen, but we have to eat every day, so the woman works all day. The Bijagó woman builds the house, she the one who makes the house.

The Balanta are very good builders, aren’t they?

Yes, and everyone cooperates. The man cuts the grass, but the woman helps transport it. I was born in one of these traditional houses. But back then it wasn’t done with blocks, it was done with mud or a strip of mud like this, you put it on top, you mold it, you wait for the sun to dry it, and then another layer. Once in the morning, once in the afternoon. You have to go slowly, you can’t build quickly. But it’s very nice and it’s not hot inside. You never feel hot inside. It has a structure of sticks from the mangrove swamp, then you cross some lianas, make a grass ladder, there are no nails, it’s all tied together. The roof is made in such a way that you can sleep up there. There’s an opening here to prevent the cats and hyenas, from coming in at night, there’s a small ladder and the chicks and the hen go up there with their children and come down in the morning. All in harmony. And the roosters are emasculated and then they become quite good, they have tender meat. It’s the woman who raises animals like chickens and pigs. Men are only interested in goats for weddings. If he has a ceremony where he needs an ox, he kills one. That’s it. The man who has already been to Fanado can only raise cows.

What’s the relationship like with cattle, in this division of tasks?

The boys have to raise the cows because the man is the one who’ll be at the ceremony. And the woman has to dress the children. The man is in charge of the family’s collective work. But after the harvest, the grain is stored in a silo. It’s huge, even. There are several here, for seed, for food. At the end of the harvest, rice is divided up for each member of the family, for their needs, to buy clothes, for their personal needs. Then there’s the rice that everyone will eat. So when you plow, you think about the annual reserve, when that reserve runs out, there’s no collective rice, the woman, the son can plow privately for himself. The woman raises the smaller livestock. When you see a goat, a chicken or a duck in a family, it’s the woman’s business. But sometimes a man can borrow an animal if he needs to, but he has to pay for it. Dressing a girl is a woman’s business. For men, it’s the Fanado, but it has to be in the bush, where no one goes except the initiated. That requires a lot of wisdom and secrecy. Once you’ve been initiated, you can’t talk about it. It remains a secret. According to their behavior, we know who went to the initiation or not.

Is this Media Library space intended to be consistent with Balanta culture?

They’re going to have to maintain that, show things. They’re not children. They know a lot and they have to understand. There’s a lot that we see in one way and I know how they understand it, because I’m from their viewpoint, I was born here and I know it. The problem is that we’re proposing things that they sometimes find difficult to understand. You’re Cartesians, I’m an animist and a Cartesian. Religion is best left to others. I don’t say no, I don’t say yes, but I avoid it.

Malafo 2022. photo by Marta Lança

Malafo 2022. photo by Marta Lança

So it’s essential to have this inner commitment so that things flow without being an imposition.

Impositions must be avoided at all costs. Because they can see it as a kind of presumptuousness. Pretending that we know everything, when we don’t.

And what are the guarantees that this will be the case?

It’s persistence. To persist, yes.

But the team has a good understanding.

I know how Bedan perceives it, because I live it, I feel it and I know how to convince Pereira, who has also been to university in Romania. I’ve already talked to Beden about accepting the role of régulo, which he doesn’t want. But in practice you can’t flee, people come here to find everything they need, that they don’t know. We’ve already had to solve problems here in my village, which is bigger and more populated. It’s an ethnic and religious problem. The next day Pereira and Bedan went there, and they were already friendly. They’ve seen what war does, because nobody wins wars. They think we beat the Portuguese, we didn’t, nobody beat anything, the country exists but it doesn’t have a structure.

Not to mention the effects of war, psychologically…

We’re all neurotic and everyone thinks they won the war. I’m trying to show that with the movie I’m making. You don’t win a war. You’re left with social problems, psychological problems. A lot of people are scarred for life. You go to my village and you’ll see traces of families that the war has taken away, completely.

It’s been so many years, and it still hasn’t regenerated.

It will regenerate in another way. Vegetation is very resilient. Trees heal quickly, the human soul does not!