“Europa Oxalá”, tales of Europe

The culmination of a long research

“I live in Lisbon, and I live in São Tomé. Being European represents the new man in the global context”, a phrase from a photograph in the series Afro Descendents, by Pauliana Valente Pimentel, one of the Portuguese artists in the Europa Oxalá exposition. Who said it, the artist René Tavares, photographed in his studio of large paintings, full of freedom, covering his face with a tchiloli mask. In the series, in addition to René, there are portraits of the actresses Isabel Zuáa, Nádia Iracema, Cléo Tavares and the artists Cristiano Mangovo and Acuã Pessoa who, through their work and attitude, have contributed to our recognition of the pluri-racial, transidentitarian country and how it was time to value the stories that shape us.

Visiting the group show “Europa Oxalá” gives us a more vivid and pressing idea of the creative power, questions, prepositions, and challenges of contemporary Europe. The notion of Europe seems to be even more coincident with its reality, as with the diverse desires and memories that make it up. In the exposition hall of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, we browse through the 60 works in languages such as painting, drawing, sculpture, film, photography and installation, by artists whose names are not a mere list but a source of knowledge about identities, decolonisation, xenophobia, racism, migratory processes of people, worlds and materials and art. Aimé Mpane, Aimé Ntakiyica, Carlos Bunga, Délio Jasse, Djamel Kokene-Dorléans, Fayçal Baghriche, Francisco Vidal, John K. Cobra, Katia Kameli, Mohamed Bourouissa, Josèfa Ntjam, Malala Andrialavidrazana, Márcio Carvalho, Mónica de Miranda, Nú Barreto, Pauliana Valente Pimentel, Pedro A. H. Paixão, Sabrina Belouaar, Sammy Baloji, Sandra Mujinga and Sara Sadik, all of whom figure in the international art scene, represented in galleries and museums. They are Europeans with a strong connection to Angola, Madagascar, Cape Verde, Congo, Benin, Guinea, Algeria, and Burundi, often speaking the languages of these countries, and they live mainly in Portugal, Belgium and France. Their proposals are not anchored in the territorial question, at most they would be trans-territorial. In general, and it is part of the game to generalise diverse works in a collective exhibition, “Europa Oxalá” inscribes personal histories (as a point of view of oneself towards the world and towards the other) in an idea of a community of blood vessels where the same history of each one circulates and where recognition is given to the fluid place from which they depart, are or are projected. Without producing an overly didactic discourse helps us to reflect on Europe today, because “art does not repair the wounds of history, but it is a fundamental field for thinking about the politics of the present”, as Carla Baptista wrote about the exhibition in “Le Monde Diplomatique”.

With the co-curatorship of Aimé Mpembe Enkobo, Katia Kamelie and António Pinto Ribeiro, it makes sense that this exhibition on transits in and to Europe, circulates precisely through the old continent: it opened in Marseille (at the Musée des Civilisations de l’Europe et de la Méditerranée), is present at the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, in Lisbon, until August 22, and will follow to the AfricaMuseum, in Tervuren, Belgium.

One of the interesting aspects is the timely timing of the exhibition when the decolonisation of institutions, museums, restitutions and reparations is being debated. The artworks and the artists that are chosen, contribute to disrupting the always problematic classification of “African art” as the art of a certain niche. On the other hand, the exhibition promotes artists who have Africa in their European life and contribute to the salutary process of Africanisation of Europe (which has always been Africanised), giving an overall view without being confined to the expected and reductive horizon when grouped together as African artists or of African descent. According to the Portuguese curator, Pinto Ribeiro, “Europa Oxalá” marks precisely “the ideal moment to clear the colonial myth and the post-colonial melancholy designated as ‘African art’”.

Another very positive note is the strong representation of many women artists, being the status of women in contemporary society one of the exhibition’s agendas. The modes of production, discursiveness and criticism, and the syncretic languages used are clues for us to understand the contemporary world.

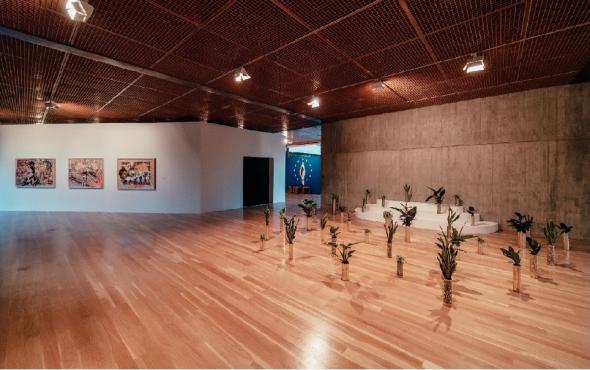

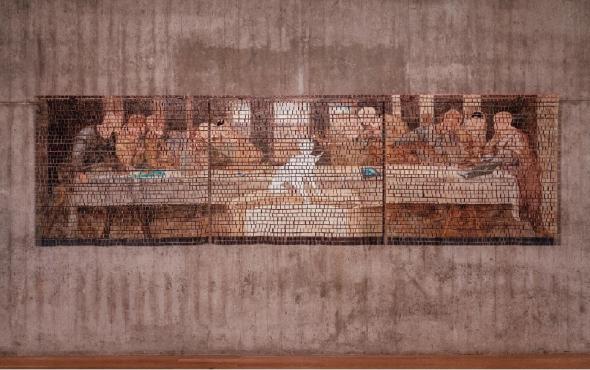

View of exhibition. ©Pedro Pina/Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian.

View of exhibition. ©Pedro Pina/Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian.

Post-memory: I have not experienced the problem but it occupies me

The exhibition “Europa Oxalá” is part of Memoirs – Sons of Empire and European Post-memory, a comprehensive scientific project directed by Margarida Calafate Ribeiro (Centro de Estudos Sociais, Coimbra), which has given us insight into the visions and thoughts of artists “from post-memory”, who share the colonial heritage. This project resulted in hundreds of articles, interviews and publications, including the books Novo Mundo: Arte Contemporânea no tempo da pós-memória (by researcher and programmer Pinto Ribeiro), Não dá para ficar parado: Música afro-portuguesa. Celebration, conflict and hope, by journalist Vítor Belanciano and a book with the same name as the exposition with essays by Amzat Boukari-Yabara, António Pinto Ribeiro, António Sousa Ribeiro, Ariella Aïsha Azoulay, Cécile Bourne-Farrell, Christine Bluard and Bruno Verbegt, Fabienne Bideaud, Lisette Lombé and Margarida Calafate Ribeiro.

This important exhibition, accompanied by an intense cultural and educational programme in dialogue with the themes and the works of these artists (which is essential, since the exhibition itself does not contain much information) is, therefore, the culmination of Memoirs‘ research. From the outset, it will be fundamental to provide clues about post-memory, the non-hegemonic condition of those who share traumatic experiences not directly lived, transmitted deeply in a family environment. Second and third-generation artists from ex-colonised African countries are affected by such memories “in deferred”, indirectly, among memories of family and friends’ experiences, who transmit to them stories, images and cultural practices from their cultures of origin. Families have often gone through colonialism, decolonisation processes, colonial and civil wars, migrations, exiles, various displacements, and some violence – symbolic and on the skin, and have experienced Europe in a hybrid condition, and formatted to hierarchical paradigms that result from the colonial issue. From these immense and varied experiences, the artists draw material for their artistic production and original reflection, they resignify personal or institutional archives, they narrate their composite identities, and they use intelligence and creativity as tools to overcome family and collective traumas. They show us certain angles and subjects with the necessary personalisation and subtlety that we do not find in the agendas of ephemeris, political programmes or in abstract concepts such as interculturality, inclusion, decolonisation of minds and cities.

View of exhibition. ©Pedro Pina/Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian.

View of exhibition. ©Pedro Pina/Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian.

The desire for the future and possible otherness

The auspicious title “Europe Oxalá” works by phonetic and semantic force. “If god wills” “Insha’Allah” in Arabic, or “Oxalá” from “Let’s hope so”, carrying future wishes for the Europe of today. May the so-called post-colonial condition be assumed, may racist and power asymmetries be overcome, and white hegemony be stabbed once and for all. However, these works are not on the level of denunciation or resentment, but rather on the level of so-called reparation. There is no nostalgia for a return to our origins, but rather a gesture of affirmation of the cultural wealth that constitutes them and which is inevitably connected to a change of paradigm in the conception and experience of Europe1. If it is true that the cultural heritages of these artists contribute, in tension and perspective, to the cosmopolitanism of Europe, they also reveal to us the various faces of so-called European interculturality, showing the contradictions of modernity, global capitalism and of the artistic and knowledge canons (still markedly eurocentric). For example, by combining contemporary languages with traditional processes and ways of knowing their origins. Driven by curiosity, I went to try to better understand the artistic and reflexive meanings of what I was observing in the exhibition.

Almost at the end of the room, we find copper artillery pieces used in Belgium in the World Wars, acting as vases for flowers. In a country where the icon of our revolution is the carnation in the rifle, it may not be original. However, these flowers, in the collective exposition enveloped by the vision of the Gulbenkian’s fresh gardens, originate from the mining areas of Katanga, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where the conflict has been going on for decades. Thus, the installation by Sammy Baloji, a Congolese artist living in Belgium and organizing the Lubumbashi Biennale, summons up the violence of the colonial past and the current one: occupation, war, extortion, wounded and refugees, as well as the drastic consequences of the force of weapons and the increasing militarization of the world. In other words, the deconstruction of colonial history contributes to the decolonisation of the world.

Dada (2018), sculpture by the artist of Algerian descent Sabrina Belouaar (Paris, 1986). Two fists in plaster with a belt, which here loses its function of sustaining, to oppress, and punish, the two closed fists of revolt and struggle. We read that the work summons the memory of her father, a worker in a belt factory. In addition to the sculpture, Belouaar surprises with the photograph “The Gold Sellers”, in which the hands of an Algerian woman with gold rings stand out. Adding the context, the image gains more strength. In some Islamised countries in West Africa, women suffer the double oppression of family and society, being disowned and discriminated against at the slightest deviation from the code of conduct (for example, by insinuations of adultery). When they leave home, they carry on their bodies what they can, and are forced to sell their jewellery, making their only asset their business.

A critical perception of Europe by Aimé Mpane has in Ngunda (2018-2020) a potency. In this work we see the flag of the European Union struck by a central tear, a kind of silhouette of the Virgin. Around the “hole” the community stars are yellow daffodils and at the base are square tyres, therefore unviable. Mpane questions the sacralisation of the European Union’s authority, its guidelines, ‘treaties’, hierarchies and its threatened foundations: peace and democracy. Other works that contribute to resignifying the knowledge or the perception, always subjective, that we have of the world are the cartographies by Malala Andrialavidrazana (originally from Madagascar), such as Figures 1883, Reference Map for Business Man or Figures 1876 or Planisphere Elementaire. In an interview on the website of the C.G. Foundation the artist, who associates regional and worldwide atlases and references, such as record covers, that marked his generation, says he wanted to show “how certain actors in the world try to pull the strings for the benefit of a very small number of people rather than the majority”.

In line with this macrogeographical vision, Fayçal Baghriche, of Algerian origin, has conceived a globe that rotates uninterruptedly, at such a speed that the continental and geographical contours of each country become blurred and dizzy, in a gesture that renders national identities and flags insignificant. In the interview about the exhibition, Baghriche notes that this frenetic globe becomes “a mural where nations disappear and only stars remain, like the erasure of differences.” Defending a globalised and general position of art: “we cannot remain circumscribed to certain artistic practices of our region” or to “claim at all costs a culture of belonging”.

Djamel Kokene-Dorléans, an artist working from the minimal, talks in the interview about his sculpture of a pair of inverted shoes topped by cement, as if imagining the disappearance of a body, “a metaphor for prehistory, our personal stone, it is the rock of the modern human”. The installation is part of the No Reason series, which makes a philosophical reference, as well as a reference to the multiplicity of reasons for the things Wittgenstein advocated.

And we move on to artist John K. Cobra’s words from the concept “of trans-architecture, which has a radical, transcultural, national and gender fluidity. Human beings have to arrange the space and time, the opportunities and also the rituals where they can explore different facets of their identity without restrictions or categorizations that have been put in place by capitalism, imperialism, etc. Art as a way of looking at spaces of negotiation between human beings but also objects.” In the defence of the fluidity and performativity of identities, voluble and transgressive is the choice of materials for some of his works, such as rubber from the Congo which, in colonial times, was a symbol of power and domination. Cobra sculpts rubber-covered bodies that translate movement and uses Kwanga (a consoling bread and also a symbol of life), wigs, leather, and brass, to create counter-images to the oppressive strategies of colonial and capitalist identities and violence.

I sit and watch a video by Katia Kameli, a director who has reflected on colonial miscegenation. Le roman Algérien (2016), dives into Algerian history and memory, taking us to a street in Algiers, where Farouk Azzoug and his son have a visually cacophonous kiosk. Old postcards and all sorts of photographs are sold there. Through this random collection lined with plastic, we travel through architecture, vintage advertisements, brands, Algerian or visiting personalities, and icons of all kinds. This iconographic assemblage allows us to enter the country’s history in subjective connections, temporalities and references, woven by Algerian interviewees.

Finally, works more connected to technologies and digital culture. Camouflage waves #2 (2018), by Sara Sadik, shows the ink print on film of the image of choreographer Adrian Blount, to which a plastic texture is added giving the impression that the body will dissolve. The French multidisciplinary artist Josèfa Ntjam weaves neo-futuristic fictions of imaginaries in which digital technology is relevant. In the video Mélas de Saturne (2020), we see associations between blackness, the Greek term mélas, darknet and virtuality in a mythological journey.

View of exhibition. ©Pedro Pina/Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian.

View of exhibition. ©Pedro Pina/Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian.

Portuguese-speaking artists and universal language

At the entrance to the exposition, the series of images Tales of Lisbon, by Mónica de Miranda immediately catches our attention. I follow the montage accompanied by the words of Djaimilia Pereira de Almeida, Kalaf Epalanga, Yara Monteiro, Ondjaki, Telma Tvon, the writers were invited to write from objects and belongings that are lost and helpless after the demolition of the houses. Devoid of their sentimental aura, stripped of their functionalities and belongings, we see floppy disks, suitcases, shoes, dolls and notebooks corroded by time. This sound and visual installation refers to the psychological and social violence that is the loss of a house, a neighbourhood, geography, or a memory. The big question of the right to housing and its dignity is the unequal way in which citizens are treated. The notions of belonging, of family, of the stories of the “peripheries”, are here touched on in a poetic and unpretentious way, recreating the experience by suggestion in situations, unfortunately still so recurrent, in metropolitan areas. The artist Mónica de Miranda has worked in various neighbourhoods capturing images in the construction of an artistic documentary archive on the transformations of the human and urban landscape, namely in the neighbourhoods of Talude, Azinhaga dos Besouros, Fim do Mundo, Mira Loures, 6 de Maio and others, mostly inhabited by Africans and African descendants.

By the Angolan artist Délio Jasse, who lives in Italy, we could see the mural Terreno Ocupado, composed of 24 blue images, worked by emulsion. The artist tells us that, since his return to Luanda, after 12 years without having been there, he has photographed “as if he were an anonymous person who did not know the city, concentrating on architecture”. Playing with territorial issues, the architecture that is disappearing to make way for recent architecture, the processes of eviction (houses left behind by the Portuguese) and occupation, we see the cultural confluences of present-day Luanda and discontinuities in terms of territory and regimes.

The artist Márcio Carvalho, from a multiracial family of Angolans and Portuguese, lives in Berlin and presents two drawings from the series Falling Thrones, in which Josina Machel and Patrice Lumbumba, as if they were athletes, confront the statues of King Leopold II and D. João I. The power structures of the Olympic games and the entire sporting competition appear as a metaphor for the anti-colonial struggle between iconic figures of independence and symbols of colonial oppression.

We are also gripped by the drawings of Pedro A. H. Paixão (Angola, 1971). In La Lupara (2020) we see a biracial woman sitting in a chair, a portrait in coloured pencil from a photograph of the artist’s great-grandmother. Her fixed, haughty gaze destabilises us, as if in a tired rage, as does the weapon her long fingered, long nailed hands carry.

Artist from Guinea Bissau, living in Paris for many years, the painter Nú Barreto is fixing his memories on cardboard support, in the series Traços, Diário (2020), a mosaic of small paintings. The influence of comics can be seen in the sequences and composition, in the contrasts, and in the characterisation of the figures with black arms, almost always unbalanced and distressed. In an interview with Sumaila Jaló on the BUALA portal, the artist contextualises this series Traços Diário (I, II, III) as a self-imposed challenge: to draw daily “everything that crossed his mind”. In the first phase, he was concerned with “the consequences of confinement, as well as the return of Humanity. During the creation of these works in a context closed off from particularities, being an artist, confinement/isolation was not something new. My life is completely isolated, required by professional needs. Despite this specificity of my work, I ended up feeling, at a certain point, the weight of confinement, even with the privilege of having everything around me. In the second phase of the drawings around the problem of confinement, I became interested in the question of the freedom of beings in a confined space. Questioning: what good would a small or large space do without freedom? The idea is to propose or open a dialogue around the question of Excess and Sparsity.”

Carlos Bunga works with poor materials such as cardboard to make an improvised shelter, the vulnerable box, the ruin, opposing monumentality and accumulation and spectacularisation, the anti-monument.

The already mentioned photographs by Pauliana Valente Pimentel of Portuguese Afro-descendant’s dialogue with the series Nous sommes Halles (2002-3) by Mohamed Bourouissa. These are portraits of young people from the Parisian banlieu who gather in the historic shopping mall Lei Halles, proudly displaying their streetwear style and clothing. We read that this project interacts with the book Back in the Days by Jamel Chamazz, which documents the beginning of hip-hop culture in New York in the 1980s in Brooklyn, Queens, or Harlem, bringing in the trends and breakdance. Also, in the line of pop culture, is Francisco Vidal’s screaming painting, with its figures, faces, strokes, words and music, poetry and affirmation.

View of exhibition. ©Pedro Pina/Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian.

View of exhibition. ©Pedro Pina/Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian.

Emancipatory artistic practices and agents of culture

Why does analysing art trends help us think about the moment we are living in? António Pinto Ribeiro reinforces, in his book Mundo Novo (New World), that these artistic projects insist on revisiting and deconstructing colonial narratives, rejecting History based on monumentality and heroicity, being inspired by feminist and ecological debates, on underlining racial and cultural discrimination through personal stories, on investing against the colonisation of imaginaries, against racism. Without ignoring the tensions and violence of a region that has taken itself to be universal, we find in Europe, in contexts of freedom, incredible manifestations of afropolitanism as a cultural movement that makes Africa the meeting point of different migratory movements. There are many worlds in the composition of Europe, which has been made up precisely of the cultures of the whole world, usually with the arrogance of sucking in all the knowledge and labour force. Thus, an exhibition with such emotional force, of memory and artistic experimentation, does contribute to the decolonisation of the arts and of a certain idea of the world from Europe. Europa Oxalá paves the way for the recognition of the multiplicity of memories and what we still have to go through in a Europe with so many ambitions and problems.

More info on the exhibition and interviews with the artists.

Notes

- This article was written when the exhibition Europa Oxalá was on display at the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, in Lisbon, Portugal, from March 4 to August 3, 2022.

- The exhibition will be on display at the AfricaMuseum, in Tervuren, Belgium, from October 7 to March 5, 2023.

Article originally published by World African Artists United at 11/10/2022.

- 1. It is worth understanding what Achille Mbembe diagnoses as a paradigm shift in Europe that has always considered itself the centre of the world. “For a long time, Europe allowed itself to be lulled, almost without restraint, by illusions. Had it not decreed itself to be the only place where the truth of man would be unveiled? The whole world was at its disposal. In modernity, Europe came to believe that its life and culture, unlike that of other civilisations, were driven by the ideal of a free and autonomous reason. This had made it the pivotal continent in the history of humanity, an entity both apart and omnipresent, a universal being and a manifestation par excellence of the Spirit. To borrow the words of a famous critic, Europe knew everything, possessed everything, could everything and was everything”. In Brutalism (Antígona 2021).