“My art is not made of technique, but of feeling”, an interview with artist TOY BOY, in Luanda

Toy Boy has followed the various stages of the country’s post-independence and initiated his artistic practice after the civil war. His work is an expression of life in Luanda, intrinsically linked to the suffering and creativity one feels in the streets. In tune with the city’s artistic movements and circles (such as Elinga Teatro and Fuckin’ Globo), Toy Boy tells us his story with the sincerity and sensitivity that describe him. Dribbling the difficulties in his path and the need for survival, he appropriates a certain pop art, making collages or ready-mades, installations, and using recycled materials such as rust, but, above all, he gives body and voice to the singularities of urban life. In Luanda 2022.

How was your artistic yearning born?

We always had creativity here. We used to make tin cars, we invented balms to polish shoes.

What was that like?

We’d burn tires, mix them with diesel or petrol, and polish the shoes of the guys who gave us change. It also comes from pop culture itself. In the eighties, there was a certain pop world, with rooms filled with posters of Bob Marley, Bob Dylan, and George Michael. I used to pick up cans to sell to friends who had wonderful collections of cans from foreign co-operators. Thus, the artistic drive came from my own experience and the pop art I felt around me. And from the people around me.

The friends with whom you connected, the artistic tendency of the city?

It was a great possibility to be side by side with very fine artists at the beginning of their careers. They were very good, creative, alternative, with a lot of energy, and freethinkers, something I wasn’t used to in my neighborhood.

How did you start to get along with them?

I joined Elinga through Kiluanji Kia Henda, who took me from a takeaway in Mutamba, where I was working, and dragged me to Elinga Teatro.

Already at the time of the Nacionalistas (artists’ collective)?

Yes.

What did you do?

I was their producer, the “handyman”. I liked that world, I was super in love with it, because it was different. Elinga’s collective spirit led me, and many others, to a more prominent productivity.

How do you see the importance of Elinga at that time (from 2004 onwards)?

It was an art barn, a place where people could do what is now done naturally, like collages, pop art, the free expression from the Elinga movement. With those components, music, theatre, visual artists, contemporary dance.

António Ole had his workshop there…

Yes, and the gatherings. We’d stay there talking, from 11 a.m. until midnight. We seemed crazy to society.

In those early days, did you collaborate with the theatre?

Yes, as a stage assistant. I had the opportunity to work at the 1st International Festival of Theatre and Arts, as a production assistant in two plays at that festival. A great artist, Pedro Campelo, came to work with scenography. To have participated in the production, to follow Pedro’s strength, to produce a festival with various companies, and to be there every day working hard was a great experience.

What fascinated you about scenography?

Having to set things up and to create. The group would come in and say ‘We want this’, and we would have to develop a story and set it up for what the others wanted.

You were never an artist with an inflated ego?

No, because I came from that school, I don’t have that.

And you start presenting your own work.

I start painting my first tiny project with A3 sheets and crayons. I went to Nelo Teixeira’s studio and said, “those abandoned pencils and sheets over there, pass them on to me”. And I made “Esboços de Jazz” (Jazz Sketches) in 2007. Nelo Teixeira even told me to exhibit it, but I wanted to do it with some elegance, and I ended up not displaying it. It went into someone else’s hand and disappeared. At the time, I did not have a steady place to keep my things.

You lived for some time in Master Paulo Kapela’s studio…

Yes, I lived with Kapela. Before that, I slept at Elinga, in the dancers’ small storage room. Then came Movimento X, with Pedro Gil and Mano a Mano, a night underground, bar, and program that occupied the whole theatre, and I had to leave.

I went to Lisbon for three weeks, but I returned early because I needed things here that belonged to me, and I had to come and collect them. When I came back to Luanda, I had nowhere to stay. My only corner was really Capela’s goodwill, he was also ill, and I stayed looking after him. Everything was untidy and disorganized. I stayed there for a month tidying things up, organizing, and buying him food, I prepared the food and we ate together, until Rasta Congo appeared and thought he would take care of Kapela. I was very sensitive and ended up leaving there and went to live at Mano Maninho’s house in Mártires do Kifangondo.

In terms of artistic techniques, how was that time with Kapela?

It was always good to see Kapela working. He worked every single day.

Was he an affable or reserved person?

He had phases, many when he was not well, others when he received you well, then we also knew how to notice when he was not lucid, out of balance, and when he was available to people.

Was the Kapela universe truly special?

It was special. It was conducted with spirit, with soul, with a desire to make. It could be a heavy environment for those not used to seeing lit candles, and hanging crosses, and that mixture of José Eduardo dos Santos, Agostinho Neto, Thomas Sankara, Jesus Christ, Ubuntu, Bantu, the history of the world … it was a lot of information. He came from a religious process of the Poto-Poto school in Congo, which I believe was very good, but then he discarded Poto-Poto, Christianity, and racism, and tried to create a free thought process. Spirituality resided not only in his works but also in his way of being and seeing the world. There were no whites or blacks, yellows, those from the north or south, those who created divisions. So, in some way, he broke with this and went on bewitching people who came there, people like me and many others.

There were several focuses of artists… And the Luanda Triennial.

Yes, it was a boom.

And you start doing your own work…

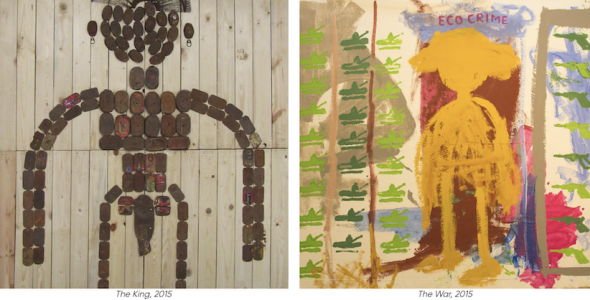

In 2008 I collected all the materials from the Theatre Festival, wood, paints, I took everything and put these pieces together in the hall of the Elinga Teatro and told the people at the bar: “you can paint”. I wanted them to create relief on two pieces of wood. I transformed all of it and called it Recycle. They were large pieces of wood, and almost all of them were sold. At the time, I didn’t have a gallery. This was an important project, but at the same time, I didn’t give it much value.

And then where did you live?

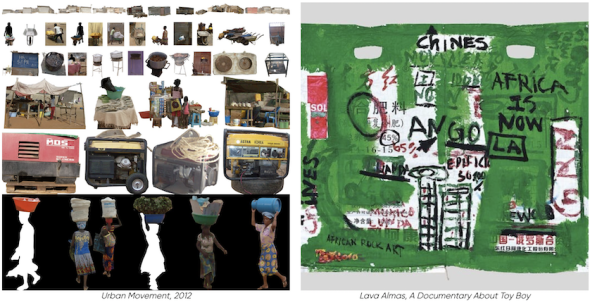

In 2010, I went to Lisbon for a short time. I returned, and I was adrift because I had nowhere to live, there was no longer Kapela or Elinga to stay with. At the Natural History Museum, I meet Kilas, who works with sound. I told him I had nowhere to work. He said he had a house in Kalemba 2. I accepted immediately. We almost went to Kalemba 2 on foot. It was a house with no windows. I took Elísio to the Roque Santeiro market to get cloths, bags, and a tarp that was usually used to cover the coal trucks that were going to Roque. I asked Mano for a $200 sponsorship. I took the material and closed myself up in Kalemba 2, and within a month and a half, I held an exhibition at Elinga in 2010, Lava Almas. It was a special exhibition for me, but a bit closed off, not many people went to see it. Mano then tells me that he’s going to make me a proper re-inauguration.

From then on, you were convinced that art was your path.

From then on, I gained security and the ability to express myself. We were all open-minded people; it was a time when people created a lot. I don’t make individual pieces; I create a project and work around that project. I guide myself through it to feel that I am doing something solid, with more identity.

Looking back from 2008 until now, how would you describe your work?

I never lived outside of Angola, which led me to connect a lot to the reality of others, the people, the architecture, and the urban movements within Angola. So my work is very local, based on the Angolan people, the country, the nation, the concept of the nation, what one wants for the future, and what one plans for a common social good.

But it has universal identification…

Of course, it does, so much so that I did the Lava-Almas exhibition in Tel Aviv (2014-15). I went back there to do a workshop at a university, a conference, and I talked to people, and there are similar things. And there were works of art that resonated with them. The African Studio Gallery bought everything.

What motivated you the most?

The way José Eduardo dos Santos governed a country made me very unhappy, it usually led me to a sort of anger, pain, and a need to express myself, and I had no way of expressing myself. Maybe it would be different if I knew how to do theatre or politics.

Has that anger died down a little, or are you still outraged?

After Zé Du’s death, I started seeing things in a great way. I am more of a kind of state adviser now. I tell them what paths they should follow to have a more cohesive, balanced, and normal society. For example, you can see this in the penultimate exhibition at Fuckin’ Globo and the last one at Epic Sana (the second edition of “Art Can be EPIC”, in July 2022).

You look for ideas, new paths, and solutions and not so much denunciation. How do you translate that in visual terms on your figures?

My art is not made of technique, but of feeling. What I feel I have to do, that I want to do, is exactly what I am going to do. For example, I spent three years picking up rust to work with rust.

You like to use recycled materials like linoleum, cotton, and rust. Why rust?

Rust brings its own charge and feeling, and in contemporary art, we can bring that feeling to people. One is not used to working with this material. In the exhibition Ferrugem (2015) I suggested the hypothesis that we were governed by Kings instead of politicians. Would we starve, thrown around as we are?

Tell us a little about the importance of the Fuckin’ Globe movement and how you interact with that dynamic.

I’ve participated in six editions of Fuckin’ Globo, an extremely engaging event. We had Elinga, which already was a very united and progressive movement. But Fuckin’ Globo brought a much more open dynamic. Not only in its aesthetic and liberal way of making art, but also the human relationship between artists. The artists were already more grown up and mature, this brought a brotherhood. At Fuckin’ Globo, you’re in another world, on another scale.

Due to the independent format?

Nobody is in charge. You do what you want. You have a space, a budget and do what you want. Be free. A place where I am given the freedom to do what I want.

Each one with their own little corner but also integrated into a collective exhibition, with a strong relationship with the public that visits each room.

Yes, all those particularities. There’s no way the public wouldn’t have been delighted with something like this. First for being something unique, second for truly being a project where the artists really exceeded themselves, went to the top, went up, and made works never seen before.

It just proves that freedom is the best incentive.

There is a small production of two people, it starts with few artists. Having a base and structure, it didn’t start from the top. Over time it starts bringing beauty and balance to the project. And there is also the marvel of mixing generations.

How do you see the difference between artistic generations?

The younger generation of artists is less aggressive, softer, and more understanding towards each other, regardless of Facebook and Instagram – they like to appear and whatnot, but sometimes they work less and show off more. They’re very show offish. But there’s a kind of understanding in them, they’re not too keen on climbing on top of each other or on competing with each other. There’s a certain balance. This is in comparison with to our generation.

Are they more focused on what they want to do?

They are much more focused, these are also different times. They have artist residencies, more opportunities to develop.

Did you have to do things more on your own?

We had to work harder.

How well do you know the deep Angola?

Photography led me to go out to see Angola. To discover if what I felt was the reality of the country. For example, to Lubango, to Gabela, which is beautiful, going from commune to commune, to the backlands: observing the reality of the people, the absence of colonization, while also trying to understand what was left of it.

And how do you see the difference in the rural world outside the big city? Do you admire the calm of the provinces?

In principle, those who have always lived in the big city want that life. But then it’s a tough life in terms of survival, in other words, the lack of support from the government is abysmal and incomprehensible. Children walk miles to school without eating a potato or having a cup of tea. Children walk kilometers without eating, without having breakfast, I have no idea what this is. I leave feeling sad. You can see the abandonment, that the government abandons people in the deepest Angola. There are beautiful things though, the teacher is at the front to accompany the pupils on foot to school, and it’s lovely to see those landscapes.

But do you sense another wisdom?

Obligatorily yes. But in the end, I feel more pity and pain, because of the poverty. It hits deep inside. If only there was support, some development within their way of being.

From the Angolan diversity, which culture attracts you most?

There is a level of originality and spirituality within the Mucubal people, an elegance about them, a look. I’ve been with mumuílas in the mountains and with other peoples. I traveled a lot by train, for example, from Lubango to Namibe, and at each stop, we saw a mixture of folks. But then, when I see a woman on the train with her breasts hanging out, carrying an ox leg on her lap, and being mistreated for having her legs apart… The guy on the train says, “close your legs”. And I feel bad, gee, but she’s fine, it’s her tradition, the sexual connotation is not in her head, it’s within a system that’s been already assimilated. In other words, there are very beautiful parts, basically what people are like, but deep down, something is disrupted, attacking the essence of people, their culture, their way of being, and their nature, always being violated.

How was the Luanda of your childhood?

I always lived in Luanda, I grew up in the Praia do Bispo neighborhood.

Were you a neighbor of Chicala?

Chicala didn’t exist, it was the beach where I bathed. There were no houses there. The sea was right here in the city. I saw Chicala being born in Praia do Bispo, there were little houses, from nice villas to humble little homes, in a neighborhood made of alleys and lanes.

You have seen the changes in Luanda…

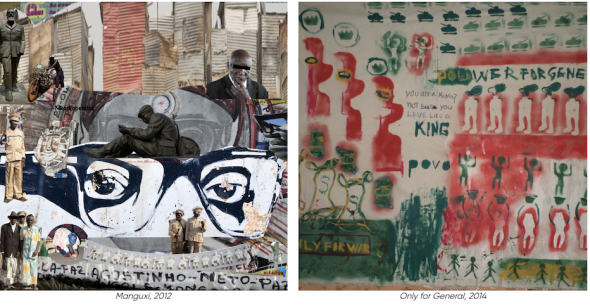

I’ve seen the various stages of Luanda’s growth, I’ve witnessed Luanda descend, and I’ve seen Luanda die. I have a project, Urbanism (2012), which discusses exactly this. Of the great fusion between the ghetto and the city. In 1992 there was a high level of immigration of people from the provinces. Everything runs through here. The hills are born right there behind my house. From the Palácio, ghettos and favelas spring up everywhere. Everywhere. Even in the city, they expanded outwards. Everywhere. It wasn’t my city anymore, it was something different. I couldn’t walk around much anymore. If my mother’s friends, Jehovah’s witnesses, saw me in the favela, they would tell my mother. And I liked going to the favela to see how they lived, who they were, and try to understand. I walked through all the favelas, I roamed all of them, I searched all of them.

What attracts you to the life in the musseque?

I still live in the favela, even though I live in a house with better conditions than the others. It’s a very dense favela, the Estalagem. What attracts me are the children growing up in that world, running over rocks, we are afraid that they will fall, but they don’t fall, and even when they do, they get up and continue to play. They don’t have toy cars, they don’t have dolls, they play mummy and daddy, something they pick up, a Cuca cap, a lid from an insecticide can to make sand funge, and they make there their game. Sometimes I would film them because it’s too beautiful. However sometimes I feel that conscience. After the Urbanism project, I thought to myself, “this is people’s lives”, What I’m doing is not exactly art. You see more what people’s lives are like, sometimes I feel like that. I don’t feel like producing Urbanism and working in that way, although I also call it photo installation because I use Photoshop, install, and create stories.

And with sound.

I took two megaphones and paid these ladies to shout the words onion and okra. To give a voice to that of the street vendors, to show the world what these people are going through.

Why the name Toy Boy?

In Luanda, everyone has a street name, and I have had this name since I was a child. I was born in February 1976, at the time of the boom, post-independence, and everything was already very confusing. And my mother gave me the name Toy because my father is António Nbazela, in homage to him. It was thought that my father was dead. He had run away to Zambia, without giving any news, he was hiding. My father turned up five years later.

But why did he run away?

He was a man with a very democratic capacity. He was a friend of Chipenda as he was a friend of Holden Roberto, as he was a friend of Savimbi, as he married a cousin of José Eduardo dos Santos. He had a very democratic mind. He was a teacher, and he taught politicians how to do politics. The problem was that if you were not familiarized with and connected to party X, you could no longer deal with party Z. This was very complicated for an already very democratic mind like my father’s. At the time, they were persecuting and even killing intellectuals.

Your father has been in hiding, reappears, and manages to reintegrate well?

He shows up and goes to work at the United Nations and opens a school in a house in Mártires do Kifangondo. At the time, skills were needed, and he started teaching private lessons. I went to live with him, and while he was teaching, I would play with people’s children. I had freedom, my house was where everyone came to play. My father pretended not to see that there was a mess. We had a vegetable garden and a water tank that was our swimming pool.

And he took good care of the child?

Very well. To this day, I don’t understand how this worked. The man had a lot of power. It was a very different thing.

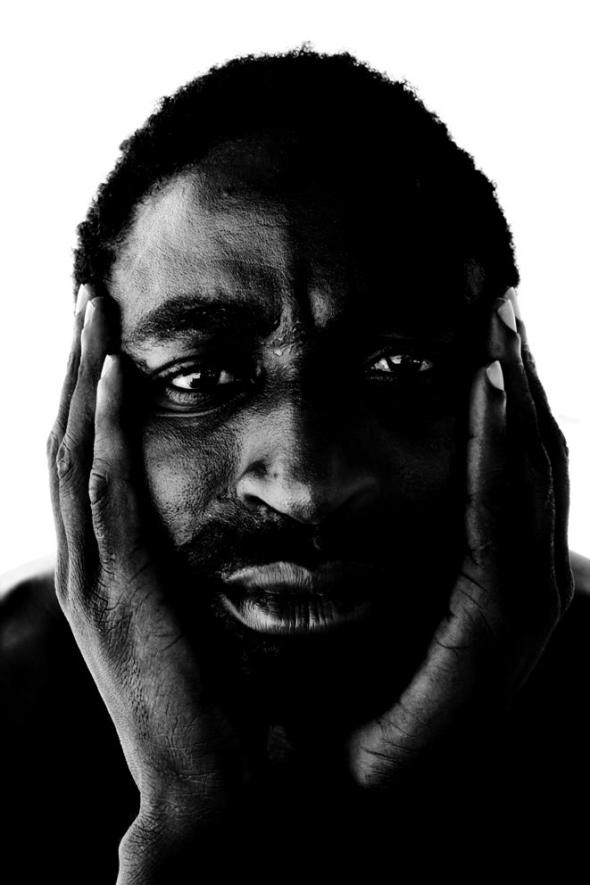

Toy Boy by Rui Antunes

Toy Boy by Rui Antunes

So, back to your name. Toy is explained, why did you adopt Boy?

Boy was born in Praia do Bispo. I was given the name Toy Boy as a child.

As an artist, has it always stayed that way?

Although it’s a name that alludes to a “boy to play with”, I discovered over time that it wasn’t very relevant, people knew it wasn’t like that. Like it’s said Manguxi for Agostinho Neto, everyone here has a name.

We are giving the name its own personality…

Article originally published in WAAU.

More information about the artist at Jahmekart Gallery.