Superintensiva

What is this intervention about? It is not only about one issue. It’s about intersections.

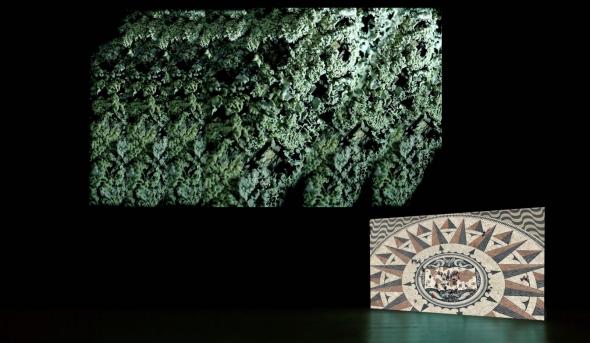

Let’s cross an olive grove of various shades and intensities. It’s important to do it here, in the centre of Lisbon, where the olive trees are discreet and ornamental. For example, the ones in the olive garden in CCB, or in front of Jerónimos. One cannot think about this without recalling the centuries of discovery journeys, imperial depredation and occupation that precede us.

Or the memory of the rurality in the city’s suburbia, like the alleyways of Carnide, for example.

Or the words that Jesus Christ said on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem, from where he was taken to the great sacrifice.

Anyway, all around, the olive tree can’t be taken apart from history.

A secular (and biblical!) tree, a poor relative of agriculture, lately flustered by superintensive production. Its life cycles are accelerated, the percentile curve stagnates early. Productivity is what matters, there you have it. That is to say, this has been happening for some time in the new agricultural universe of Alqueva’s irrigation farming.

The equation is more or less like this:

Profits maximized by investment funds, on the one hand. Exhausted soils and difficult regeneration, on the other.

Or: Physical, human, labour transformations of a region. Or: From the country’s barn to the intensive olive grove. Or: From dry farming to irrigation farming. Or: From the golden of the cornfield to the petroleum-green of the olive grove. Or: From green to black to get to the golden of the olive oil. Or How to create wealth by sowing poverty. Or: From the old cereal farmer to the mega-estate ownership regulated by international money. Or: Nobody defends monoculture, but we walk towards it.

Or a simple question: How does olive oil get to our dishes?

And a personal observation: a Lisbon citizen moves inland and realises that there’s more to her country than the landscape.

**

To the south of the Tagus river there are those who are shouting ecocide when referring to the olive and almond groves, and other superintensive farming experiences.

What does the ‘echo’ from eco-cide echo in us?

There is nothing I can add to what is thought and done about these old problems that are now discussed by more people who are aware that it will be better to live in a good environment… I thank farmers, scientists, young people, anonymous people, communes and communities, activists, and all the micro-experiences that denounce, boycott or mitigate the economic and social model that brought us here.

Here where?

Here where the situation is serious!

**

”We want to breathe!” GAIA Alentejo calls for the “Stop the Ecocide” demonstration in Beja, in September. Quoting a text by Filipe Nunes, from the newspaper Mapa.:

“In one of the most vulnerable regions to the climate crisis and where the desertification process is clear, we have seen in recent years the implementation of an agricultural model based on a monoculture system, which extends to several regions of Alentejo and Algarve. There are several types of impacts and they range from: pollution and over-exploitation of water resources; soil erosion and loss of biodiversity; occupation of protected areas; destruction of archaeological heritage; noise pollution - to the slow but lethal impact on the health of all living beings that inhabit these regions - both through pesticides and fertilizers applied near the villages as well as through the extraction of olive pomace oil. Adding to all this are also the problems resulting from the use of migrant labour, people who often live in degrading conditions and are practically subject to slave labour”.

**

When our grandmother beheaded chicken, my brother begged: “don’t kill the animals, let’s go buy food at the supermarket”.

When did this happen? Ignoring the death of other beings in order to live. Wishing we didn’t know about the destruction around our bubble.

Was it when our parents moved from the countryside to the city?

Was it when our thumb started to touch the screen more often?

Animals? Only pets. Jungles? Only urban ones. In our houses, we clean up everything that reminds us of the dust from where we came from. Little pigs go to school, cats wear boots, play the piano and speak French, crickets are our consciousness, Elsa is the name of a depression, Katrina of a hurricane, Bárbara of a storm. Savagery instead of a country. Elements of land and sea as resources. People as users. Identities as consumption objects.

Consuming, consuming to stabilise this fucked up disruption.

**

The future now:

Monitoring crops and farm work. Drones, satellites, GPS and aerial field observation. Sensors measure temperature and humidity. The emotional life of pigs and fruit quality monitored by screens. Modified cucumbers and corn. The fly, whose bite affects the olive, is fought with pheromones.

(pheromones are volatile substances segregated by females that have the function of sexually attracting males.)

It is called “Precision Agriculture”.

Oh well! Nobody wanted to go back to working their fingers to the bone anyway.

In 2002, boom! The floodgates of the largest artificial lake in Europe – Alqueva – are closed. Guterres was not yet one of the blue helmets but he had on his head an engineer’s safety helmet when he was showing off the splendour of public construction works. With SO MUCH public money invested in a dam, there was enough water to solve the problem of drought and its impacts and to get rural world to produce in large quantities.

What exactly is the problem now that there is no more shortage of water?

“It is for water that one still kills and dies inland, comrades. Let us bury the hammer and sickle and raise the hoes again!”

Things got out of hand. As the land in Andalusia was already depleted, Alentejo was assaulted. The intensive system grows at the rate of one thousand hectares per month.

It already covers about 75% of the irrigation area in the Alqueva perimeter. Anything goes.

Setting up an olive grove is considered “reforestation” and combating desertification THEREFORE, it is an operation subsidised by community funds. The land has lost its social function, warned a Communist MEP.

The land and its endless purposes: it belongs to those who work it, it is an asset in the pocket of rural-millionaires, it is a place of common belonging and sharing. The humus of the land is a blender of inert and living matter.

And wasn’t the water for everyone? The water flows, like finance.

People from Alentejo living on their small hill, in their village and community. Reserved and ancient-mannered people. Large areas of land. Low population density, the age pyramid pointing mostly to the elderly. Good wines and gastronomy, the ideal relaxation for city getaways.

But, in the end, Alentejo is a laboratory-reserve for political-landscape experiences. Its people, resilient to misery, drought, depopulation and exploitation, turn all this into an agrarian dystopia, so to speak.

**

This project began to emerge in Minor Asia during the Upper Palaeolithic. This project began to emerge in my mind when I was looking for better quality of life, i.e. fresh air and space, to raise a child. Ourique, capital of the Iberian pork with its back and spareribs and all sorts of loin cuts, such as belly and cheek loins. On a hill subject to dry farming for so long, wildflowers sprout inside and out of the small wall made by stone-on-stone.

On the road, I see white pegs aligned in a sort of American-cemetery-style. A few months later, hedgerows of olive trees stunted in their size and top growth, early production, assisted by herbicides and agrochemicals to disinfest and fertilise. I close the windows because of the pestilent smoke of olive pomace, used as fuel and biomass. I can picture contaminated particles in the smoke, in the water lines, on our clothes, in the walls, in the lungs. I can picture the logging of full-grown holm oak trees to be replaced by the monoculture of olive groves.

We don’t see people, but we know all about labour exploitation and negligent public health.

**

SO, in short:

- Predatory purpose of the agroindustry: contaminated air and time.

- Resilience of the olive tree, guardian of prophetic languages and of the Mediterranean, godmother of our stews. The twisting of its trunk and its ancestral wrinkles. Symbol of longevity. Perennial tree, long roots of six metres that absorb water and mineral nutrients. Arid or poor, any soil that has calcium carbonate makes a thriving olive tree. In addition to the olives and the olive oil, it is used for firewood, charcoal, shade, fuel, lighting. It has also therapeutic and aesthetic uses.

- The tasty olives, especially the Galician ones. With bread, cheese, garnishing the local specialities - Bacalhau à Brás, bitoque and pataniscas. But, just like the grapes are grown mainly to produce wine, what matters is to produce olive oil and put it on the market.

Wondering through the olive trees lovers also find their path. In Abbas Kiarostami’s film, the actors play a couple, married after the 1992 earthquake. In a long sequence shot, the actor pursues the actress trying to persuade her to marry him. You can hear the wind whispering among the trees.

**

“I can’t breathe,” said Eric Garner just before he died, strangled by the order of New York’s Police Department, 2014. “I can’t breathe,” said George Floyd Jr. strangled by a police officer in Minneapolis 2020.

We want to breathe, say the millions of people contaminated by Covid 19 and the workers wearing masks 8 hours a day.

We want to breathe, shout the 80 inhabitants of Fortes, in Ferreira do Alentejo against the smoke released from the chimneys of a factory belonging to a Spanish group, less than a hundred metres from their houses. And Maria Joaquina Camacho used the expression “the dark side of economy”, recalling a morning, in the middle of the fog.

Another morning of a damaged planet.

The olive trees must also be really short on oxygen, being as tight as they are.

**

The olive grove revolution seen through the eyes of the progress optimists: If an exceptionally good olive production would yield an average of 3 tonnes, an intensive and superintensive hectare of olive grove produces up to 12. In 10 years’ time, the same accumulated production of 70 years of a traditional non-irrigated olive grove is obtained.

Like that, Portugal has gone from being a chronic importer to the fifth largest exporter of olive oil in the world.

**

According to the geographer Orlando Ribeiro, the “granite civilization” is linked to the north of the country in the same way that in the plains of Alentejo you have the “clay civilization”. In Alentejo the clay soils were moulded according to the interests of all times and this clay land structure shapes the history of the territory.

The land is a palimpsest of violence. During dictatorship times, deforestation of moorlands and the monoculture of cereals were imposed, - the famous Wheat Campaign, in the 1930’s conducted by Linhares de Lima.

With the end of the Agrarian Reform, the fields became abandoned and unproductive. Some small and medium sized plots of land were subsidized for reforestation with cork oaks, holm-oaks and pine trees. The large estates lied in fallow waiting for the Alqueva dam and its water distribution in the interest of agricultural productivity. One can see the intensive cultures of this irrigation farming system everywhere: on the roadside, in the villages, interfering with our imagery of an Alentejo that, in part, no longer exists.

The Wheat Campaign (1929-1938) An initiative inspired by Italian fascism, during the Portuguese dictatorship, in favour of Portugal’s self-sufficiency in production, an autarky model. It included measures such as customs protection and a fixed price for wheat.

Extensive areas of olive and oak trees used for grazing Iberian pigs were replaced by cereal crops, achieving an ever-increasing cultivated area.

The Alqueva irrigation almost surpasses this milestone of the wheat campaigns. A century later: The farming and grazing areas are now replaced by intensive olive and almond groves, which means destroying roots, causing water stress, suffocating trees, and their natural regeneration.

**

15 billion trees are logged every year. 100 million new olive trees have been planted for monoculture.

“When the trees that still resist disappear, there will be no others to replace them”.

And still: “The tree does not die within a year, but it is doomed”.

And still: “The forest in the south does not burn like in the centre of the country, but it burns without being seen”. It’s like love.

**

The giants of olive groves production in this decade:

Six groups own the Elaia/ Sovena / Oliveira da Serra olive grove – 10 thousand hectares; De Prado – 10 thousand; Olivomundo 5 thousand; Innoliva 3 thousand; Bogaris 3 thousand. Beneficiaries of public investment 2.5 billion. Great olive oil ambassadors of the world: Sovena / Oliveira da Serra and Gallo / Jerónimo Martins. And I leave un-listed: Areas planted per farm; Annual production in tonnes of olives; Production of litres of olive oil; Export.

**

My house is on the edge of a Special Protection Area, at the end of Alentejo, on the way to the Algarve. The village is ugly, we feel like we are in a Twin Peaks countryside universe, and it takes time to gain trust. The coming of a child reconnects me to the earth and appeases the suspicious gaze of the city dwellers who occupy part of the land, consult the Borda d’Água almanac and try hard as neo-rural people. It also helped to create the habit of having lunch by myself in a tavern, listening to the news from the agricultural world and making caricatures in my own way.

A house in the countryside is inhabited slowly. It will never be ready, even when I am old, reading Ellena Feranti near the heating stove. I bought it in ruins. It took: Embracing the past as the water still ran along the water sheet to the well that supplies the house. Planning sewage and electricity channels, treating the limed walls, plastering, gluing tiles, raising roofs, discovering the old floor under the cement. Planting seeds that did not sprout the first time. Taking baths in ever-drier dams. Living repeated cycles of minimal differences: new stork nests, each year more sedentary. The mantle around: from green to yellow to brown. Plucking insistent wild herbs. In springtime, preparing the garden with the neighbour who provides tomatoes, onions, cucumbers, courgettes, and watermelons. It took: working days, bonfires with out-of-tune chants, lots of brandy, lots of cigarettes, New Year’s Eves, retreats of feminist groups, autonomists, tourists, artists. A high-risk pregnancy, slowing down to read novels. My daughter started her life with a strong relationship with the countryside. She took a lot of naps, played a lot, she took the town hall van to go to school through dusty roads. There lived some English people from the BBC, some Paulistas who had escaped the massacre in Brazil. Sarah designed houses made of clay. She set up a weaving studio: she carded the wool of her neighbour’s sheep, spun the wool and wove.

**

In a red robe, grilling mackerel under an olive tree, Eurico told terrible stories from when he worked with travel fair marketers.

They never paid me a salary, they gave sour soup to the whole team, confiscated documents. I had to carry heavy iron cables and ride bumper cars all over the country. Every day racist insults. After many months of torture, I managed to escape from Santarem only with the clothes I was wearing.

It remains there, under the olive tree, a bit of Eurico’s angry look.

**

The Covid 19 burst, as did the bizarre weather. Discoveries, anxieties, appeals from childhood, envisioning life. In the temporary joy of the deconfinement, the artistic residence of TERRA BATIDA helped to give some meaning to the landscape where I lived.

Alentejo cannot be Burnt Land.

**

In the meantime, a question arises:

- Why is the surname Oliveira [Olive Tree] so famous in Portugal?

The dictator Oliveira Salazar / the film director Manuel de Oliveira / the singer Adriano Correia de Oliveira / the singer Simone de Oliveira / the writer Carlos de Oliveira / the opinion maker Daniel Oliveira.

**

In a documentary from 1979, women pick olives in a cooperative, while one of them is distributing water:

- Men earn more than we do, but the work is also different, they climb to the top of the trees, we walk on the ground.

- Women don’t beat, they crawl.

- With the Agrarian Reform, only those who don’t want to work don’t do it. This was hard work back in the day as well. I have worked since I was 12 and I raised four children.

- It’s a work contract. We pick up a certain number of bags, then we go home to do whatever we have to do. – It depends on the abundance of the harvest. It depends on the amount of work that needs to be done. It’s from dawn to sunset.

**

The “superintensive” olive groves have 1850 to 2100 trees/ha and the olive harvesting period extends from October to January. Multidirectional vibration machines, which in one day do the work of 20 people, are used. Automotive machines are used, with a working capacity of 3 hours per hectare. The “vibrator + fruit trimmer” is placed and a knife cutting bar allows two lines of trees to be pruned simultaneously, on either side of the treetops. The machine tightly adjusted all around the olive tree makes an oscillating movement, with vibrating rods, and shakes it; the olives fall on a conveyor belt which throws them into a container. Once chosen, the healthy olives go to the mill.

Night harvests affected the avifauna, but after so many birds were ruthlessly vacuumed by the machines, night harvesting was officially forbidden.

**

I count 37 olive trees on my little piece of land. Each olive tree in good condition is equivalent to 3 litres of olive oil in the cooperative’s mill. I prefer to preserve them. We harvest the olives from the 5 fertile olive trees, between October and November, they get shrivelled if harvested too late. Good year, bad year, crop and counter crop. 2020 the harvest is difficult for everyone. Bad luck is affecting everyone.

There were the olive trees, silent and bare. Trunks corroded with lichens, no trace of olives, petroleum-green leaves like shoals at the moon, zero olive oil production. Zero the wonderful charms of extra virgin olive oil: taste, seasoning and health benefits.

It was speculated: Was it the cleaning phenomenon when the bad weather came with the season of change from flower to fruit? I saw them flourishing in April. Was it the Xylella bacteria that affected so many olive groves in southern Italy? A friend of mine thinks that the ultimate cause will be the waste of water resources by the intensive farming system around our small lands, converted into properties.

I lack the wisdom of pruning, which we could apply to ensure survival. Cutting off branches from our tree to give more strength to the fruit.

**

“Paranoid institution, platation system lives constantly in a fear system basis. In several aspects it is similar the requirements of a ploughing field, a public square, or a paramilitary society. Platation system gradually becomes an economic, regulatory, and penal institution. One of the most effective forms of accumulation of wealth in other times, accelerates nowadays the establishment of mercantile capitalism, mechanical labour and the control of subordinate labour”. wrote Achille Mbembe.

**

Sugar cane. Coffee fields. Palm trees. Soya fields. Corn. Eucalyptus. Cotton. Alfafa. Sugar beet. Olive groves. Almond trees groves. Constantly cultivating, without fallow, producing for market quotas. Die early and spread death.

**

“Olive trees, olive trees/ Olive trees, olive trees/ From afar they look like lace embroidery/ Rise up on people / Don’t rise up on farms”.

**

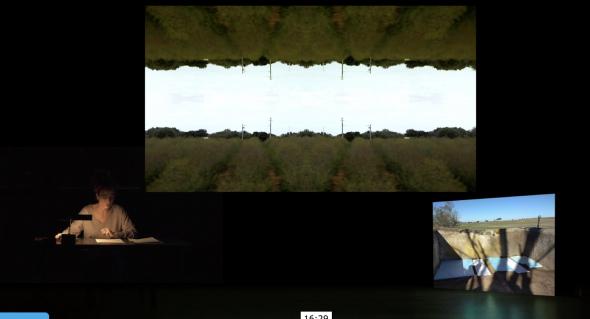

Lecture-performance Festival Alkantara 2020, Teatro São Luiz, part of TERRA BATIDA.

By and with Marta Lança, Video essay Maria Mire; Sound Nuno Mourão.

Network of people, practices and knowledge that contests ecological violence and the politics of abandonment in Portugal, considering local, global and multispecific scales. Program by Rita Natálio and Marta Lança.