De/Re-Memorization of Portuguese Colonialism and Dictatorship: Re-Reading the Colonial and the Salazar Era and Its Ramifications Today

Memories are constitutive of contemporary culture. Maurice Halbwachs suggests that memory should answer the interests and desires of today, and thus the past is consecrated or omitted accordingly.[1] Memory works as an everyday construction, that combines feelings, realities, points of view, and intentions. The tendency to “correct” the past in a sense of unity, peace, and consensus, even when it comes to the most egregious violence that may even imply those who celebrate it,[2] often works in response to the present and current social and political issues.

Concerning memory politics in Portugal, we can sense a kind of identity crisis. The non-recognition of the violent past of colonialism has been a practice of political power, in the face of the fact that it is the longest lived colonial empire in world history (it existed for almost six centuries, from the capture of Ceuta in 1415 to the hand over of Portuguese Macau to China in 1999[3]). It has become a common sense to naturalize violence by repeating the mainstream narrative of a certain idea of Portugal—constructed on the base of the Gilberto Freire’s[4] theory of “lusotropicalism”[5]—in which the great adventure of the “Discoveries,”[6] soft colonialism (attenuating stories lined with glorious deeds), or the Lusophony approach as harmony of cultures linked with a common language, are ways to compose the trend of de-memorization. This is a subtler stance than historical revisionism, because it does not misrepresent the facts, but the framework in which we interpret them.[7] This trend omits and devalues the tragic and uncomfortable moments of history, often capitalized for tourism masked by glorious celebratory myths. In other words, more than four decades after the end of this long Portuguese colonialism, it is still hard to discuss the colonial legacy and the continuities of the imperial history — especially the racism that affects black and gypsy populations.

However, recently there has been some room for debate and action around the issue of decolonization by artists, scholars, media, and activists aiming to decolonize mentalities and proposing concrete policies. Black activism has gained media space, action, and discussion groups. We can observe a stronger recognition of the fight against structural racism, including the denunciation of police violence and the expression of black and intersectional feminism. Steps toward representativeness are being taken. In addition to having a black woman as Minister of Justice,[8] who has just been elected to the Portuguese Parliament for the first time, there are three other black members of parliament. Some great associations led by black women like DJASS- Associação de Afrodescendentes (Afro-descendant association) (2016), FEMAFRO—Association of Black, African and African Descent Women (2016) and INMUNE—Black Human Institute (2018), and the historical SOS Racismo (1990) denounce and struggle against all forms of racism, invisibility, and discrimination of African-descent people in Portugal. They suggest diversity quotas for universities and public function works, as well as the inclusion the ability of Portugese citizens to understand racial inequalities with credible information.[9] They demand concrete measures such as the new nationality law,[10] the revision of school curricula, the collection of ethnic-racial data.

In this article I will consider symbols, presences, and absences in Lisbon, relating the city’s history and public memory. Then I will analyze two artistic examples that question our way of transmitting history: one of performative arts, A Living Museum of Small and Forgotten Memories (2014) by the Portuguese artist and theater director Joana Craveiro/Teatro do Vestido, and the photography series New Man (2010-2012), by the Angolan artist Kiluanji Kia Henda.

Public Displays of Colonialism in the Streets of Lisbon

Portuguese national identity has strong roots in the imperialist history,[11] which is reflected in its national iconography. The city of Lisbon is immersed in an imperial imaginary: from the neighborhood of Belém to the Eastern zone rehabilitated for the World Expo 1998 called Parque das Nações, or the Avenue Almirante Reis (a label of multiculturality with shops, catering, hairdressers, religious signs of several cultures.) Throughout the city, references to the colonial past are omnipresent.

The neighborhood of Belém is recognized for its concentration of national monuments and public spaces, particularly the evocative site of the Maritime Discoveries and marked in 1940 by the Portuguese World Exposition. One of these monuments, Padrão dos Descobrimentos, was first erected in 1940 in a temporary form with perishable materials, as part of the Portuguese World Exhibition.

![Padrão dos Descobrimentos [Monument of the Discoveries], Lisbon Created 1939 by Portuguese architect José Ângelo Cottinelli Telmo, and sculptor Leopoldo de Almeida for the Portuguese World Exhibition opening in 1940. Padrão dos Descobrimentos [Monument of the Discoveries], Lisbon Created 1939 by Portuguese architect José Ângelo Cottinelli Telmo, and sculptor Leopoldo de Almeida for the Portuguese World Exhibition opening in 1940.](https://www.buala.org/sites/default/files/imagecache/full/2022/08/01marta.png) Padrão dos Descobrimentos [Monument of the Discoveries], Lisbon Created 1939 by Portuguese architect José Ângelo Cottinelli Telmo, and sculptor Leopoldo de Almeida for the Portuguese World Exhibition opening in 1940.

Padrão dos Descobrimentos [Monument of the Discoveries], Lisbon Created 1939 by Portuguese architect José Ângelo Cottinelli Telmo, and sculptor Leopoldo de Almeida for the Portuguese World Exhibition opening in 1940.

The monument was reconstructed in concrete and rose-tinted stone masonry in 1960 to mark 500 years since the death of the Infante Dom Henrique (Henry the Navigator). The monument represents a caravel with symbols that allude to the characters of the Portuguese overseas expansion: cultural, navigators, cartographers, warriors, colonizers, missionaries, chroniclers, and artists. The attached Centro Cultural das Descobertas was opened in 1985, with a viewpoint, auditorium, and exhibition hall. It is now run by the City of Lisbon and features programming with some reflection on its own history and symbolism. This expresses a willingness, and some openness, on the part of the municipality of Lisbon, to critically evaluate the building’s connotations.

The marks and imagery of the colonial empire are omnipresent in the streets but, until recently, are decontextualized and lacking critical reading. There is still no truly post-colonial gesture: neither the history of colonial violence nor resistance to colonialism is told. If one observes the toponymy of the streets in Lisbon, one can face a lot of names of military men and colonial administrators. These namesakes of streets carried out devastating “pacification campaigns” in Africa and committed ethically reprehensible acts (such as General Roçadas, Paiva Couceiro, and Mouzinho de Albuquerque) throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. It is necessary to point out the crimes and deeds rather than mythologizing, naturalizing, and even heroizing those kinds of figures. Today we know more about those colonizing actions. Billy Woodberry’s film, Story from Africa (2018),[12] which uses photographic archives of the violence of conquering movements, demonstrates the violence implicit in the existence of these monuments. The film focuses on the territory of the Cuamate people of southern Angola, conquered by Alves Roçadas in 1907. A great avenue in Lisbon is named Avenida General Roçadas. He is described only as a military hero.

Concurrently, there are no monuments to African personalities up to this day.Amílcar Cabral (1924–1973), one of Africa’s foremost anti-colonial leaders, a theoretician, revolutionary, who led the liberation of Bissau-Guinean and Cape Verde, and who was assassinated in 1973 would be a obvious first candidate. As an exception to this absence, one could mention the project “The African Presence in Lisbon,” by the Batoto Yeto Association. The association provides guided tours highlighting the historical African presence in Lisbon. This association will soon inaugurate plaques identifying the most important places, a bust of Pai Paulino (1798-1869) a decorated as a liberal combatant and mediator of conflicts involving. A statue alluding to the African presence in Lisbon will also be erected.[13]

Another promising initiative comes from the above mentioned DJASS-Afro-descendant association. They aim to promote a memorial for enslaved people conceived by a “black” lusophone artist that will be shortly chosen. This memorial (set to be ready in 2020), will be produced with a grant from the city of Lisbon, a Participative Budget of Lisbon City Hall. The initiative will provide the public with concrete information on Portuguese involvement in slave trafficking and slavery in Lisbon. The purpose of the memorial is to pay tribute to the memory of the millions of Africans enslaved by Portugal between the 15th and the 19th centuries. The memorial will also pay tribute to the members of resistance movements involved in the promotion of the historical recognition of Portugal’s role in slavery and trafficking. It will bring the legacies of this long period in Portuguese society, from the rich African cultural heritage to contemporary forms of oppression, into public consciousness.[14]

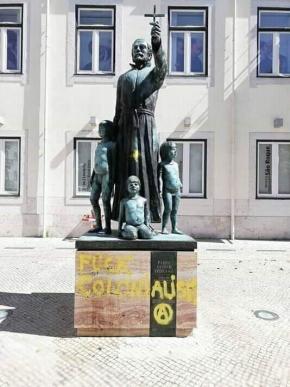

In 2017, a statue of António Vieira (a Jesuit priest and member of the Royal Council to the King of Portugal in the 17th century) depicted in a gesture of conversion with three indigenous children was placed in the center of Lisbon. The statue provoked demonstrations and implicated Vieira in the Portuguese evangelization and slavery of Indians. These actions were met with retaliation from Portuguese far-right groups who gathered to ensure the so-called safety of the statue. The dispute was highly symbolic: to some people the statue alludes to the memory of domination over indigenous peoples For others, to protest against the statue is to undermine a great figureinPortuguese literature and history. The artist Pedro Neves Marques’ short film Art and Hurt (Toxic Image on the Street), allowed activists to speak directly with the statue. The film’s synopsis explains the present moment: “Lisbon is changing. While afro-descendants claim their right to the city there is also growing debate about the public monuments and symbols of Portugal’s colonial past…”[15]

Statue of António Vieira erected in 2017 in LisbonThe Urgency of Decolonization in the Arts, Museums, and Academia

Statue of António Vieira erected in 2017 in LisbonThe Urgency of Decolonization in the Arts, Museums, and Academia

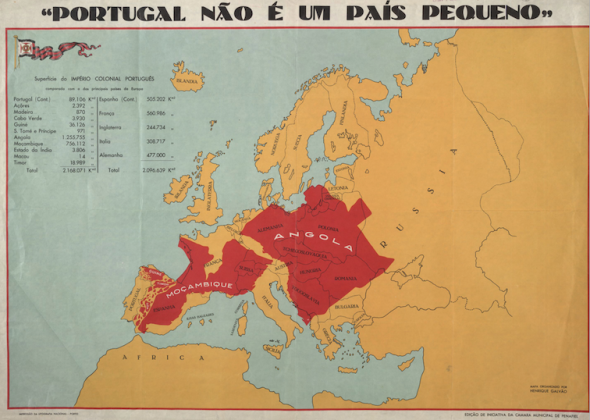

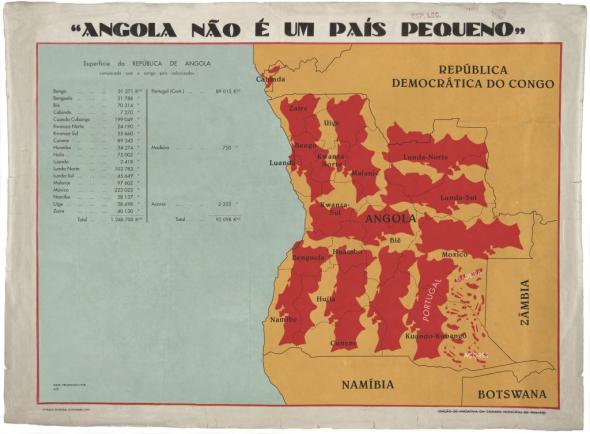

During the Salazar dictatorship there was a persistent ideological maintenance inthe justification of colonialism. The poster “Portugal is not a small country” (1934), one of the most striking images of the period’s propaganda, was presented at the Colonial Exhibition in Oporto in 1934.[16]The poster, which has versions in French and English, impresses the throbbing slogan through the junction of verbal and visual elements. Why is not Portugal a small country? The image justifies the assertion by superimposing maps of the Portuguese colonies on a map of Europe. Spain, France, England, Italy, and Germany are lost to surface of the Portuguese Empire. If Portugal, with its colonies, is greater than the “principal countries of Europe,” equally colonial powers, “little Portugal”surely secures a place amongst them.It does not reproduce a map, but an overlay of maps, creating a non-existent geographical representation. In 2011, the Portuguese architect Paulo Moreira ironically inverted the sense of the weight of countries in geopolitical logic with the inscription: “Angola is not a small country,” referring to the greatness of Angolan territory. Moreira’s updated map reevaluates Portugal-Angola relations: those of interdependence and competition, former colonizer and colonized.

Henrique Galvão 'Portugal is not a small country'. Map for the Colonial Exhibition in Oporto, 1934

Henrique Galvão 'Portugal is not a small country'. Map for the Colonial Exhibition in Oporto, 1934

Paulo Moreira. Angola is not a small country, ongoing research since 2011

Paulo Moreira. Angola is not a small country, ongoing research since 2011

A new generation of historians, such as José Pedro Monteiro, Miguel Bandeira Jerónimo, Miguel Cardina who work on the subjects of the colonial period and national identity. These historians analyze the most violent events, like “forced labor,” and the politics of difference in European colonial empires: namely the ideological and institutional instruments of engineering and legitimizing the political and socioeconomic differentiation within colonial empires. The historical intersections between internationalism and imperialism and the colonial war also feature prominently. As an example, I would like to mention the project MEMOIRS – Children of Empires and European Postmemories led by the scholar Margarida Calafate Ribeiro at Center for Social Studies, University of Combra. This project focuses on the intergenerational memories of the children and grandchildren of those involved in the decolonization processes.. Through interviews of second and third generations, and a comparative analysis of the cultures influenced by the postmemory of the colonial wars and the end of empire, the project reinterrogates Europe’s postcolonial heritage.

There has also been a younger generation of Portuguese artists (also Afro-descendants) who are bringing marginalized histories and perspectives to the fore. In performative arts, Teatro Griot, founded by Luanda and Angola born performers[17] Mala Voadora,[18] Teatro do Vestido (that I will analyze below), and Hotel Europa[19] work with post-memories[20] and methods of transferring history. In visual arts, the work of Grada Kilomba, Pedro Neves Marques, Vasco Araújo, Filipa César, Mónica de Miranda, Délio Jasse, Catarina Simão, and Pedro Barateiro have offered an image that clashes with the celebratory and nostalgic visions of colonialism. Each approach questions colonialism, articulating it to the conditions affected subjects and bodies located outside the main meta-narratives and imaginary of the Portuguese past and its post-dictatorial, postcolonial present. The work of these creators is attentive to the multiple ways in which a supposed postcolonial debate can provoke a disavowal of criticism.

Grada Kilomba, Still of Illusions Vol. I, Narcissus and Echo, 2017. Colecction Moderna Gulbenkian

Grada Kilomba, Still of Illusions Vol. I, Narcissus and Echo, 2017. Colecction Moderna Gulbenkian

One can visit the third floor of Museu do Aljube[21] in Lisbon (a museum dedicated to the history and memory of the fight against the Salazar dictatorship in the building of the former prison for political prisoners), to learn (in a hardly problematized way) about remarkable aspects of colonialism, the liberation struggles of the colonial peoples, the colonial war, and, furthermore, the solidarity of many Portuguese towards this struggle. If we look at the name of the room dedicated to this history: Those who stayed behind, we might hope it contemplated the system’s victims, or seek a little information about the resistance to dictatorship and to colonialism from both sides. But there are only Portuguese names. We lack other points of view. But cannot attribute this problem solely to the Aljube Museum.

There is a considerate amount of film and book production about the colonial war, but these publications are by Portuguese authors and focus mainly on the Portuguese victims and Portuguese political issues In 2015, Independência, a film by Angolan filmmaker and producer Mário “Fradique” Bastos / Geração 80 about the liberation war (note the difference between using “colonial” vs. “liberation”) against Portuguese colonialism, was born from the need to preserve the history of those who participated in the liberation struggle of Angola. Many are still alive and lucid but few have had the opportunity to talk about their experiences beyond family and friends. The film, although professionally made and addressed to new generations, was not thematized in Portugese public debates, as it should have been. The film did not feature in festival or television circuits.

Many approaches are weakened by their failure to connect the contemporary situation with the past. The formal end of the colonial situation did not put an end to the structural inequalities deriving from Portugal’s colonial experience. Decolonization must be understood as a crucial yet-unfinished and evolving process. The decolonized posture will depend on the positions that emerge from this process in relation to the most urgent contemporary conflicts.

A Performance Lecture Questioning the Transfer of Memory

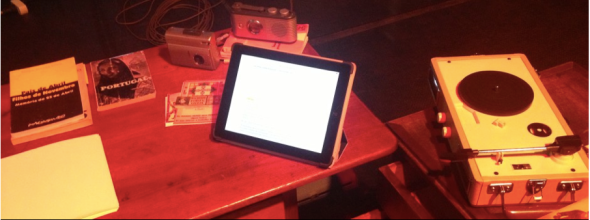

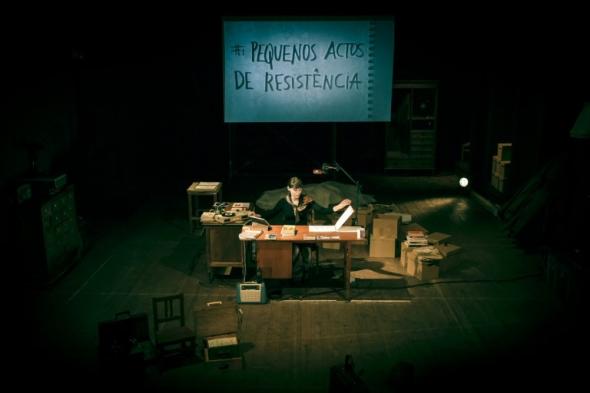

Joana Craveiro /Teatro do Vestido. A Living Museum of Small and Forgotten Memories, 2014

Joana Craveiro /Teatro do Vestido. A Living Museum of Small and Forgotten Memories, 2014

The above statements about invisibility (and attempts to reveal) of colonial memory in the city, are affirmed through the lens of the Estado Novo/New State dictatorship (1926 – 1974) and the anti-dictatorship resistance and revolution. The case study analyzed here addresses the interplay of the memory of both of the Portuguese dictatorships and colonialism through performance. A Living Museum of Small and Forgotten Memories[22] (2014) by Portuguese artist Joana Craveiro/Teatro do Vestido can be described as an example of memorization; contrary to de-memorization, as it problematizes the ways of producing and questioning memory. This project, using documentary and autobiographical texts, has been presented several times since 2014; in parallel to celebration of the 40 years of the Portuguese democracy. In the official celebrations of the Revolution of April 25, politicians usually talk about “heroes” and “fathers” of the Portuguese democracy, which was born after the Revolution against the Salazar regime. Craveiro’s approach is to untangle and contemporize the intricacies of this story, so that memory does not crystallize on one particular time. By featuring the perspectives of anonymous people, cast and created by a young woman, this work disrupts the old owners of memory in Portugal: the so called “heroes,” the politicians, the men.

Joana Craveiro/Teatro do Vestido. A Living Museum of Small and Forgotten Memories, 2014

Joana Craveiro/Teatro do Vestido. A Living Museum of Small and Forgotten Memories, 2014

This four-hour piece consists of one prologue, and performance-based lectures organized in seven acts which were originally presented in four independent sessions. The material comes from a repository of testimonies, and through Craveiro’s selection criteria, are turned into an interpretative monologue that calls on many voices through an inclusive construction: “The Museum is mine, but it also belongs to the people who had never had a voice and whose voice I wanted to hear.” These other voices include members of the resistance to the dictatorship (spread in movements but under the huge influence by the Communist Party that existed since 1921), political prisoners (mainly in Caxias and Aljube prisons), returnees,[23] historians, filmmakers, neighbors, school colleagues, friends of parents, and family members. The Living Museum urges audiences to reflect on the intersections between, on one hand, personal, collective and cultural memory and, on the other, history and parts of the history that we never learned or almost forgot.

The commitment of the artist to work with memory from the enunciation point of “here and now” implies that what people remember is not necessarily the historical truth. The exercise does not neglect the possibility of including what could have happened, using an approach where memory acts like an alternative time or story. Some people involved in the narration could say “The person I was at that time and who I am no longer” or the self-irony of the elderly stating “We were like that.”

Joana Craveiro/Teatro do Vestido. A Living Museum of Small and Forgotten Memories, 2014Concerning the Revolution itself, even in her position as the inheritor of a reality that she did not live through—from a position of postmemory—Joana Craveiro puts the auto-biographical memories (about the history being told to her) on the same plane as other people’s memories. Appearing in various testimonies, both lodged in her Living Museum, and are reinforced by technologies or artefacts of memory (films, pictures, records, tv shows, songs, political icons, images, an assortment of souvenirs and objects). When researching, Craveiro found a box with books that her father was meant to donate to the Documentation Centre April 25,[24] and then she shows some of them and another boxes where we can access some very significant objects.[25] Because of their ability to be re-appropriated, these kinds of artefacts unleash powerful dynamics between memories and identities. They are open to subjective interpretations in a new reading of materials and testimonies that expand them in time. Craveiro organizes the stories and the speech from an object, not only as a metaphor but like a formal document of a “museum.”[26] Less desirable and honest methods of narration often show and name objects at a frantic pace, in an effort to light up connections to our own stories and visions of this period.

Joana Craveiro/Teatro do Vestido. A Living Museum of Small and Forgotten Memories, 2014Concerning the Revolution itself, even in her position as the inheritor of a reality that she did not live through—from a position of postmemory—Joana Craveiro puts the auto-biographical memories (about the history being told to her) on the same plane as other people’s memories. Appearing in various testimonies, both lodged in her Living Museum, and are reinforced by technologies or artefacts of memory (films, pictures, records, tv shows, songs, political icons, images, an assortment of souvenirs and objects). When researching, Craveiro found a box with books that her father was meant to donate to the Documentation Centre April 25,[24] and then she shows some of them and another boxes where we can access some very significant objects.[25] Because of their ability to be re-appropriated, these kinds of artefacts unleash powerful dynamics between memories and identities. They are open to subjective interpretations in a new reading of materials and testimonies that expand them in time. Craveiro organizes the stories and the speech from an object, not only as a metaphor but like a formal document of a “museum.”[26] Less desirable and honest methods of narration often show and name objects at a frantic pace, in an effort to light up connections to our own stories and visions of this period.

The final act “When has the Revolution ended?” raises a crucial point. It begins to question the terms that people use according to the political trend: revolution (in the leftist imagery) or coup d’etat (somehow discrediting the revolutionary potential of those days). It investigates competing narratives and conflicting mindsets related to the end of the revolution (Was it just April 25 itself—the end of the dictatorship—or it was a revolutionary process until the coup on November 25, 1975?)[27] The questions broadens the sense of revolution: it’s not just a date / event in the story, but what people did with it. All these questions emerge during the play. “Which revolution are we really talking about?”, “Is this one revolution or more than one?” and “What was the general popular feeling about the end of the evolution?”

An element continuously present and guiding in the seven lectures and is the Diary, a book in which every act and lectures is entitled. The diary becomes a kind of script. But the device that enables all these materials to be screened is a camera filming everything that Craveiro shows and talks about. The books and all other materials are displayed them in sequences projected on a large screen. Through the screen, she frames books and articles with visible annotation marks. Through this alignment, the audience accesses Craveiro’s choice of superimpositions and her reporting. We are given insight into how she creates and revisits visual memories of the different periods. We see how she creates and revisits the visual memories of the most remarkable moments in the history of the second half of the Portuguese twentieth century: the dictatorship, the revolution, the so-called Revolutionary Process in Portugal and November 25, 1975. The archive in permanent construction, unstable and fluid, transforms itself into a repertoire. With the performance, the actors—real people—become characters. At the end of the play one appears carrying a card stating “This Museum Stays Alive.” By insisting in conversation with the audience at the end of the play, the author keeps adding elements to her museum that engages in the exchange of ideas, grounded in her audience’s attempts to correct mistakes or of providing new data.

Another major subject of the play is the pedagogical approach: the transmission of the revolution’s memory itself.[28] The way in which Craveiro’s piece approaches the “small and forgotten” memories allows to fill in the blanks of the simplified narrative of recent Portuguese history. In our childhood’s imagination it was something like: there was an authoritarian regime, some military heroes came and overthrew those in power, and everything changed, freedom was restored in a revolution of flowers without blood. This approach rarely articulates the situation of colonial war in Africa and how that unsustainable situation of war drove the revolution to take place. “Which omissions, revisions, erasures are happening and how are they taking place? Who is responsible for such actions? Which versions of history are we taught and which other versions can we learn?” These are the questions the artist asks in the performance’s introduction.

The Stone of Colonialism in the Case of Angola

Visual cultures linked to colonial memory in Portugal and some places in Lusophone African countries, show that traces of the defining war and slavery but are somewhat invisible inthe broader collective memory. There is not enough institutional/public interest in remembrance. African countries’ colonial history has been so violent that remembering the most violent aspects is not the most urgent public deed. The only exception is to reinforce the image of the independence hero and the struggle of African anti-colonialist movements. In the case of Angola, for example (as in Mozambique and Guinea Bissau as well), independence (1975) was followed by a series of civil wars (1975-2002). Between 1961 and 1989, the African continent was one of the main stages of the Cold War. After African nations achieved independence, alongside confrontations with former European colonial powers, they were buffeted by hegemonic aspirations for the continent of the two superpowers: the Soviet Union and the United States. In combattance of these influences,the Non-Aligned movement encouraged the new African countries to take care of their own destinies, forming international alliances.[29]

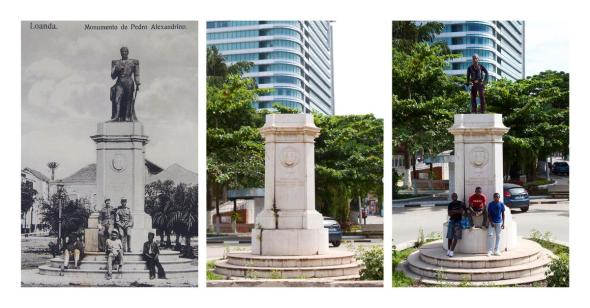

Kiluanji Kia Henda. Redefining the Power. Digital photographs mounted on aluminium, 2010. Courtesy of the artist

Kiluanji Kia Henda. Redefining the Power. Digital photographs mounted on aluminium, 2010. Courtesy of the artist

Considering the case of Angola, the country is still in a period of transformation, mainly because of the post-civil war urgency to repair the infrastructure. Kiluanji Kia Henda,[ is a well-known Angolese artist in the international circuits of contemporary art. [30 ] He belongs to a generation that was born in the post-independence era. His works are significant in the perspective it provides in what Africans have to say about the effects of colonialism in their countries. The Eurocentric perspective is typically dominant in the telling of this history.

With the series Homem Novo (New Man) (2010-2012), Kiluanji Kia Henda reformulates the historical narrative of monuments in public spaces, confronting symbols of regimes and political power.[31] The name Homem Novo comes from the Angolan national anthem, with socialist inspiration, and reflects Angola’s ambition to reinvent its national identity following its 1975 independence. In Balumuka (Ambush), the first part of the photo series, the artist photographed the statues that were gathered in the fortress of St Miguel in Luanda, before its restoration. Through a pairing with symbols of Portuguese power, like the African resistance (like Queen Dzinga) and the war symbols, we observe the moments and shuffled narratives of Angolese history.

Then, in the next phase of the project, Redefining the Power (2011), Kiluanji Kia Henda occupied the now empty pedestals with living performers: a poet and a gay activist. As opposed to the decadence glory of the colonial past, the artist was replacing the ex-colonial and the war symbols with contemporaneity, life, words and claims for today’s issues.. This work manifests a certain optimistic age ten years after the end of colonial and civil war. At the same time, it reflects on the place of memory and the role of the monument. By replacing the stones of colonialism with controversial figures, we remember the past as confrontation with contemporary Angola.

There is a perspective in the debate surrounding colonial statues and artefacts that desires to destroy and erase these traces of painful periods in the country’s history. On the other hand, it is also important to remember so that subsequent generations will be aware of what happened. And, a highly realist third way, as Kiluanji Kia Henda noticed: many people do not know what to do with these remains or simply don’t want to talk about them. Kiluanji Kia Henda explained that the 40-year emptiness of the pedestal symbolizes the lack of reflection on the history and society that was briefly experienced during the war years (one of the pedestals featured a tank during the 1980’s). “There’s always been a discussion on ‘what the hell are we going to do with those colonial monuments?’ I consider those monuments clandestine citizens with expired visas: they should be deported to their place of origin after paying the fine for illegal permanence. Or it would be a more clever decision to do an exchange with some important objects of art stolen from Africa and kept by many western museums. That would be fair.” Kiluanji Kia Henda said in an interview in 2015.[32]

Conclusion

The practice of articulating several concerns and approaches to colonial and dictatorial memory has begun to counter the sense of de-memorization linked to the state politics of memory. There are challengers to the legacies of colonial representations in Portugal and in the former Portuguese colonies, leading to the same question: How can we live well if we can’t handle our memories, even the most painful ones?

In a time of great vulnerability, in which extremism and necropolitics have become regular practice in many countries, memory/ memorization / remembrance are indeed an important sites of struggle. Thus, decolonization must be an act of liberation from the oppression of the unilateral flow of knowledge. Portugal’s colonial legacy has become a flashpoint for public discussion, triggering a sometimes militant reaction from the preservers Portuguese imperial past.

I believe that through art we can find a strong path of remembrance. Artists are able to communicate across temporalities and spaces, which traditional historiographical treatment could hardly accomplish. Artists who work with individual and personal history build empathy through works compared to academic research. Colonial monuments and street names left un-vandalized are not neutral spaces. As static as stone and tarmac may seem, memory is a process, not something carved and eternally preserved. New practices of memory preservation, from manifold perspectives, allow for addressing misconceptions and novel understandings of where certain contemporary situations emerge. In the absence of these practices, our imaginary becomes an accomplice to denials of violent that can always be repeated in unexpected ways.

Originally published by Mezosfera on 2019.

***

Notes

[1] Maurice Halbwachs. On Collective Memory (Chicago:The University of Chicago Press, 1992)

[2] Katherine Hite: Politics and the art of commemoration: Memorials to struggle in Latin America and Spain. (London:Routledge, 2013)

[3] Portuguese former colonies were Brasil (independence in 1822), Goa (1961), in Africa: Angola, Cabo Verde, São Tomé e Píncipe, Guiné Bissau and Mozambique (official independence in 1975), and transfer of sovereignty over Macau in 1999.

[4] Gilberto Freyre (1900–1987) was a Brazilian sociologist, anthropologist, historian, writer, painter, journalist and congressman. He is commonly associated with other major Brazilian cultural interpreters of the first half of the 20th century.

[5] “Luso-tropicalismo proposes that the Portuguese have a special ability to adapt to the tropics, not by political or economic interests but due to an innate and creative empathy. The aptitude of the Portuguese to form relationships with tropical lands and peoples and their intrinsic plasticity was supposedly the result of their own hybrid ethnic origin, their “bi-continentality”. Cláudia Castelo in http://www.buala.org/en/to-read/luso-tropicalism-and-portuguese-late-colonialism

[6] Jenny Barchfield, “Lisbon museum plan stirs debate over Portugal’s colonial past”, The Guardian, September 16, 2018 https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/sep/17/lisbon-museum-plan-stirs-debate-over-portugals-colonial-past.

[7] André Barata,‘Maafa’: o grande desastre.” Jornal Económico, 20th April 2017. http://www.jornaleconomico.sapo.pt/noticias/maafa-o-grande-desastre-148141.

[8] Francisca Van Dunem is an Angolan-Portuguese lawyer. She has served as the Portuguese Minister of Justice since November 26, 2015.

[9] As the current Justice Minister Francisca Van Dunem said during an Assembly of the Republic conference “Racism, Xenophobia and Ethnic-Racial Discrimination in Portugal”, that without data we can only rely on perceptions. Perceptions are that racial or ethnically differentiated population include “The economically disadvantaged; those with the lowest-skilled jobs and therefore the lowest-paid students; the students with the highest failure and retention rates and the highest school abstention; citizens with lower rates of higher education; those with a higher rate of criminal incarceration; Those who live in the periphery of the periphery, joining in neighborhoods that tend to become ghettos, not only economic, social but also cultural.” https://www.publico.pt/2019/07/09/sociedade/opiniao/francisca-van-dunem-maior-expressao-preconceito-racial-consiste-negacao-preconceito-1879342

[10] The new law establishes that the children of foreigners born in Portuguese territory (when the parents are not in the service of their home state), will be considered Portuguese by origin, provided that one of the parents has been residing legally in Portugal for at least 2 years. This contrasts with the 5 years that were previously necessary.

[11] Anthropologist Elsa Peralta, in relation to this subject, on encourages us to n: “[Consider] the Portuguese imperial experience as a part of the national ethos, independently of the positions against or in favor of the empire, which may exist today at an ideological level.”

[12]The film was shown at the DocLisboa Cinema Festival 2019. Single-channel video installation, 32 min. English, Portuguese.

[13]See: http://batotoyetu.pt/en/

[14] See also: Helia Santos: “Invisible Portuguese” Buala.org, 2019:

https://www.buala.org/en/to-read/invisible-portuguese;

Challenging Memories and Rebuilding Identities: Literary and Artistic Voices that undo the Lusophone Atlantic. New York: Routledge, 2019)

[15]Pedro Neves Marques, Art and Hurt (Toxic Images on the Street), 2018 https://www.doclisboa.org/2018/en/filmes/art-and-hurt-toxic-image-on-the-street/ Lisbon, short film.

[16] A world’s fair held in Porto in 1934 to display achievements of Portugal’s colonies in Africa and Asia. There were reproductions of villages from different colonies, along with a zoo, restaurants, a theatre, a cinema, and an amusement park.

[17] https://www.teatrogriot.com/sobre?lang=en

[18] https://malavoadora.pt/?lang=en

[19] http://www.hoteleuropatheatre.com/

[20] The concept of “postmemory” from Marianne Hirsch, describes the relationship that the “generation after” bears to the personal, collective, and cultural trauma of those who came before-to experiences they “remember” only by means of the stories, images, and behaviors among which they grew up.

[21] https://www.museudoaljube.pt/en/

[22]A Living Museum of Small and Forgotten Memories is part of the PhD thesis about the transmission of political memory in Portugal that the actress and theatre director is finalizing at Roehampton University, in London, UK. See this essay by Joana Craveiro on this performance: “A Living Museum of Small, Forgotten and Unwanted Memories”: Performing Oral Histories of the Portuguese Dictatorship and Revolution” In: Memory, Subjectivities, and Representation Approaches to Oral History in Latin America, Portugal, and Spain. ed. Rina Benmayo,María Eugenia Cardenal de la Nuez, Pilar Domínguez Prats (New York: Springer, 2015) https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1057/9781137438713_12

[23] Retornados how was known the millions of African Portuguese (former settlers) who were forced to look for refuge in Portugal during the process of decolonization 1974-75.

[24] The 25th of April Documentation Centre (CD25A), at the University of Coimbra, has an overt commitment to democracy and decolonisation. It deals with a history timeline starting with the opposition to Portuguese colonialism and the fascist dictatorship, crossing the transition to a democratic state and the Revolution of April 1974, and extending until the end of the 20th century. It is argued that, in digitally opening its collections and interacting with scientific research, journalism, literature and education, CD25A has played an important social and political role.

[25] Farm cooperatives in Portugal following the Carnations’ Revolution of 1974 were set in accordance to State policies that encouraged and supported that option. These cooperatives were run by farm workers, following the seizure of latifundia land by the workers. The legal backing for the cooperative sector during this period was widespread and applicable to all sectors of economic life, including the production and distribution of goods as well as services. As time went by, the rules and incentives, set by law, for the cooperative sector were twisted and the cooperative option became stifling, unappealing and unviable.

[26] In a similar way to the earlier artistic production of the same theatre company Returns, Exiles and Some who Stayed (2014), where a brief discussion about the colonial war and the turbulent days of decolonization took place.

[27] November 25, 1975 was a failed military coup d’état against the post-Carnation Revolution governing bodies of Portugal. This attempt was carried out by Portuguese Communists and other left-wing activists. It was followed by a counter-coup led by Ramalho Eanes, a pro-democracy moderate, and supported by moderate socialist Mário Soares, to “re-established” the democratic process, as they put it, or to stop the Communist power.

[28] Interestingly, the Argentine theater director Lola Arias also uses direct filming of scene objects on stage display. In fact, her work Mi vida después [My life after] (2009), in which six young people (of the generation born after the dictatorship in Argentina) reconstruct the youth of their parents in the 70’s from photos, letters, audio tapes, and used clothing, has many links to the work of Craveiro. Arias also presented the play El año en que nací [The year I was born] (2012) in Lisbon, in which 11 young Chilean born during the dictatorship rebuild the lives of their parents through similar methods.

[29] Cuba, for example, assisted young African revolutionaries such as Patrice Lumumba, Amílcar Cabral and Agostinho Net. Striking episodes from Ché Guevara’s frustrated stay in the Congosuch as victory in the battle of Kuito-Kuanavale (1987) through Guinea highlight this. Kuito-Kuanavale, where so many Angolan and Cuban troops lost their lives, is therefore an unavoidable milestone in the Cuban contribution to the withdrawal of South African troops in containment of white rule over the peoples of Africa.

[30] See his artwork here https://www.artsy.net/artist/kiluanji-kia-henda

[31] https://www.foam.org/talent/spotlight/interview-with-kiluanji-kia-henda

[32] https://www.foam.org/talent/spotlight/interview-with-kiluanji-kia-henda