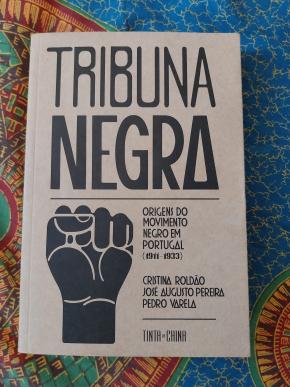

Blackness in Portugal from a different analytical perspective, a conversation with the authors of “Tribuna Negra”

A meeting with the authors of Tribuna Negra: Origens do Movimento Negro em Portugal (1911-1932), Cristina Roldão, José Pereira and Pedro Varela, resulted in this long conversation at BUALA.

The book presents a complex plot that neatly ties together the available information and many loose ends. As a research stance, the authors’ interrogative formulation, acknowledging the limitations, leaves unanswered what we still don’t know: “what have they said?”, “what have they done?”, it creates new questions and confirms how much research is yet to be done on Black Lisbon at the beginning of the 20th century. In fact, by reading the book, you get the feeling that each chapter could be another book.

The authors went to the archives, to newspapers written by Black people, and to some literature and theory (in particular the essay Origins of African Nationalism, by Mário Pinto de Andrade), mapping the Black city and leaving us with fundamental references about figures, organizations and collectives. How did ideas circulate? How was Black internationalism shaped by its disputes? What were the strategies and lines of force (notably W. Du Bois and Marcus Garvey)?

This was also a heated debate in Lisbon.

Additionally, the authors analyze the distinct positions on Portuguese colonialism and forced labor in São Tomé (“the critique of colonialism [which] was not yet anti-colonialism”), the debate on racial discrimination, the political role of Black women, the Black population working in Lisbon, relations with the left, and much more. The metaphor of an “internal conversation” is included in the desire to continue in the footsteps of a non-Eurocentric historiography, in the search for oneself and for a Lisbon where the voices of Black people have always existed.

José Pereira, Cristina Roldão and Pedro Varela, photo by Marta Lança

José Pereira, Cristina Roldão and Pedro Varela, photo by Marta Lança

Marta Lança: Starting with the sources, what were your primary ones?

Cristina Roldão: On the one hand, the sources are related to the colonial archive, for example, related to the institutions of the Estado Novo. Then, above all, we tried to work with Black newspapers from Lisbon, which have the particularity of criticizing Portuguese colonialism and communicating between Black people in different spaces. The book provides a very detailed and systematic mapping of the Black press. Not only the Portuguese press, but also the international Pan-Africanist, Brazilian or Black Marxist press, which refers to the Portuguese reality or the reality of the Portuguese empire.

ML: What are some examples of said international company?

CR: The Crisis, The Negro Worker, The Negro World of the UNIA (Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League) and Getulino.

ML: How would these newspapers spread to Lisbon?

José Pereira: The ships carried many things, including books and newspapers. With some development of the means of transportation, due to the industrial revolution, it’s not hard to imagine that there was a circulation of ideas here through the press and literature. The newspaper O Negro has excerpts from Uncle Tom’s Cabin, for example, and references the Revolt of the Lash (Brazil, 1910). It’s plausible to imagine that at least the newspapers The Crisis and probably The Negro Worker, linked to Black Marxism, reached Lisbon and perhaps even Angola and Mozambique. But we haven’t analyzed any evidence that would allow us to draw conclusions about this.

ML: We’re in the First Republic in an atmosphere in which social debates were guided by the press, which reflected what was happening in organizations, collectives and meeting spaces. Another source of information, or the main source of guidance, will be Mário Pinto Andrade, specifically his book Origins of African Nationalism. He is considered to be a pioneer of interdisciplinary Black Studies, something that does not exist in Portugal, due to the importance of his work and career. Andrade belonged to the independence generation and searched for the origins of nationalist movements (in the “proto-nationalist” generation). You, anti-racist activists of the 21st century, also give a retrospective of the movement, that is, we find a parallel stance in the search for yourselves and the collective.

Pedro Varela: The Origins of African Nationalism came out in 1997, after Pinto de Andrade’s death. It’s an unfinished book, but it was actually the result of research that the author began in the 80s. As far as we can tell, Mário Pinto de Andrade was in Guinea-Bissau, where he held a cultural post the Guinean government when Nino Vieira’s coup d’état took place, he was Minister of Culture or, rather, People’s Commissar. His book is a guide for us because there are many references there, along with the development of thought about this generation, the first step towards understanding it. We also looked for material in the archives, for example when, in 1984-5, Mário Pinto de Andrade went to give lectures in Cape Verde and São Tomé and Príncipe, where he spoke about this generation with a lot of data. Although Mário Pinto Andrade did a more extensive work on the origins of African nationalism, looking at all the occupied territories, a large part of the book is dedicated to the generation in Lisbon. I imagine that there is still much to investigate in his archive, as he interviewed or knew people who belonged to this generation.

ML: Does Andrade already offer a Pan-Africanist reading of alliances and Black internationalism?

CR: To a certain extent. We’re following the clues he left with regard to Black internationalism, but our book brings new clues to the table due to the possibilities of accessing new sources such as the Du Bois archive, for example. We bring a lot of focus to Black internationalism: for example, what is the place of the 1923 Pan-African Congress’ Lisbon section in the Pan-Africanist movement as a whole? From what we’ve been able to analyze, we might’ve not come to exactly the same conclusion as Mário Pinto de Andrade. We were able to better understand the behind-the-scenes of that conference’s construction. There are distinct forces and tensions involved. The Lisbon session took place at a very specific moment in the history of that movement and is very expressive of what was happening. What seem like accidents of logistics, delays, when you start to look at the correspondence between Du Bois and José de Magalhães, or with other figures in the organization, you realize that it’s not just a matter of logistics.

ML: Can you summarize (so that the readers feel curious and learn more in the book) the positions and lines of force articulated in this internationalism? It’s interesting to understand what was at stake and some of the positions, namely those of Marcus Garvey, Diagne and W. Du Bois, who came from a more visibly segregated world in the United States and found greater openness in Europe. Did Du Bois have any complacency about situations of racial inequality and racism?

JP: We don’t know. We ask questions about what led him to take certain positions that, to our eyes, at first glance, might seem strange. But it has to be said that Du Bois’ comrades-in-arms in Lisbon, if we can call them that, were very aware of racism in Portugal. And they would denounce it in the newspapers. And they would take a stand on another debate that developed on an international scale about racial categories, about Darwinism, “superior” and “inferior races”. This would appear in the pages of Lisbon’s Black press. We need to insist on this point as it can’t be forgotten in the contemporary discussions we’re having about racism. Generally speaking, there are two main currents in Pan-Africanism: Du Bois’ current and Marcus Garvey’s current. I’m saying between 1911 and 1927, I’m risking this chronology because, from 1927 onwards, the congress in New York was already stemming from the ebb of Du Bois’ Pan-Africanism, and Marcus Garvey had already gone through a process of arrests, had been released from prison in the United States by a presidential pardon and deported. In short, these two currents were ebbing. Then there’s the question of Black Marxism, which was a bit of a departure from them.

ML: You put Marxism forward as a kind of reconfiguration of Black internationalism.

CR: It’s one of the arms of Black internationalism at the time.

ML: Which would later have a major influence on liberation movements, etc…

JP: We don’t say that. It’s a track that runs separately, yes. Maybe we need to understand a little more, in fact, all of this could be subject to further study. We have these two currents, both of which passed through Lisbon. One didn’t want any dialogue with colonial structures at all, but rather to build a Black society in the world apart from White society and spoke of a return to Africa. This was Marcus Garvey’s current. Du Bois’ current would be more conciliatory and can be understood as nurturing some hope in colonial systems. We have to contextualize that Du Bois comes from a society where segregation was extremely violent, where there were lynchings and laws separating Whites from Blacks. The United States had just come out of the American Civil War and abolitionism. So, it’s all set. Du Bois came to see Europe. Then there was another current, of senior Afro-French, Afro-Belgian leaders, like Blaise Diagne, who were linked to the colonial administrations of their respective countries. Diagne was a deputy, a high-ranking official in the French colonial administration. Then there’s José de Magalhães who, as we show in the book, was closer to Blaise Diagne than to Du Bois…. Because of their more or less similar social origins and because they had some ties to colonialism which, despite everything, Du Bois didn’t have.

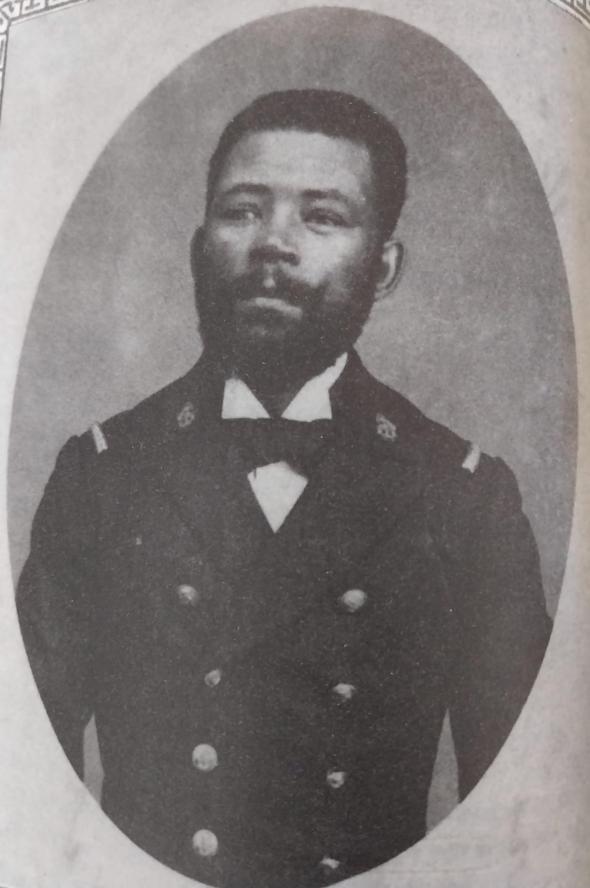

José de Magalhães in the Navy at the end of the 19th century

José de Magalhães in the Navy at the end of the 19th century

CR: When we analyze how we come to the conclusion that Lisbon is going to host the second session of the 1923 Pan-African Congress, we understand many of the relationships with Blaise Diagne, Paul Panda Farnana, and this Black elite that is in Europe’s colonial administration and circulates between metropoles and colonial spaces. Nicolau Santos Pinto, from the Liga Africana, would meet with them. We know this because he announces in one of the newspapers that a “wonderful event is to take place” and describes how this was agreed upon during his stay in Brussels and Paris. It’s interesting to think that, for Du Bois, Lisbon may not have been his first choice. As an American, and since the previous congresses (1919 and 1921) had already taken place in Europe, he was strategically thinking in a different geopolitical context. In turn, the French or the Franco-Belgians, would probably be much more interested in a European area close to their realities and interests, like Lisbon. Another line of analysis that we were very happy to follow was the possibility, or at least the attempt, to establish scenarios of a possible relationship with Black Marxism and George Padmore. We did this both through elements we found in the newspapers and through the event (which never took place) that was to be held in Lisbon, at the end of the 1920s and into the 1930s, thus after the military coup. They were trying to organize the Congresso dos Negros de Todo o Mundo.

ML: And then José de Magalhães is no longer one of the key figures, as he was at the 1921 Congress with the Liga Africana.

PV: The Liga is at these Du Bois congresses, but at the time of the Congresso dos Negros de Todo o Mundo, José de Magalhães seemed to be a little out of the “movement”. At that time, João de Castro stood out, from the African National Party (PNA), which had already existed but that, at the end of the 20s, would have more newspapers…

ML: José de Magalhães and João de Castro start out together and then fall out. Now and then you try to analyze who was more connected to the Liga Africana and the African National Party in the light of the differences in origins or type of approach. The Liga being more of a certain elite or lobby and the African National Party (of João de Castro) being more radical, sympathetic to Garveyism, and beginning to be critical of the Liga. These internal tensions are very interesting, because they show that not everyone thinks the same way and that they are what makes the wheel turn.

CR: It’s an internal discussion that’s been going on. It’s not just a conversation with the colonial institutions.

ML: And it shows that among the players in this discussion and in the movement there are various lines of thought. Does the press reflect these criticisms and conflicts?

PV: Very briefly, our study begins in 1911, when the newspaper O Negro was launched. In 1912, the Junta de Defesa dos Direitos de África was created. At that time, several figures were in that organization, namely José de Magalhães, João de Castro, who would later become opponents, Ayres de Menezes, Marcos Bensabat…

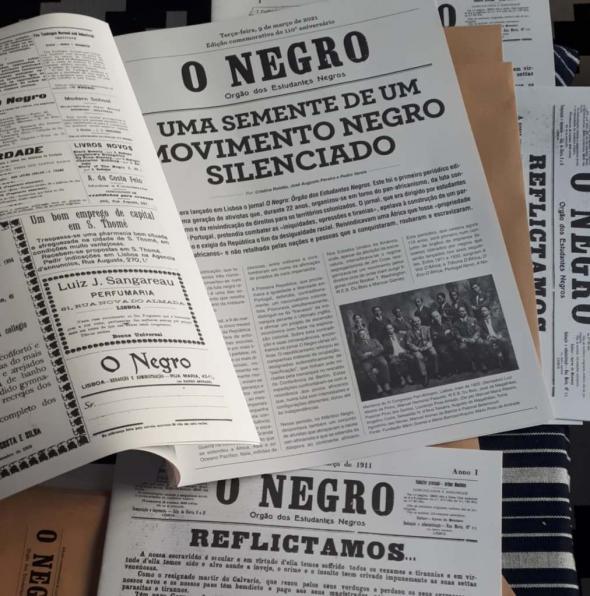

O Negro newspaper (1911)

O Negro newspaper (1911)

ML: Were they almost all from São Tomé?

PV: When we talk about this generation, a large part of them were from São Tomé. José de Magalhães was born in Angola, as was Georgina Ribas. The Liga Africana was created in the 20s and we realized that the tensions that existed in the Pan-African congresses would also affect Portugal, and this was going to contribute to a fracture in the movement. What we propose in the book is that the Liga Africana and the African National Party were opposed: apparently the African National Party had a more radical line than the Liga Africana.

Although their class origins were very similar, the people from the Liga Africana were probably better established in Portugal than those from the PNA. The African National Party had more radical stances in what was the Black movement and the Pan-Africanist movement at the time. It seems, at least in the press, to be more identified with the line of the UNIA and Garvey. The Liga Africana, on the other hand, is better identified with the Pan-African congresses of Du Bois and Diagne. But in practice it wasn’t so evident that some were of the Du Bois line and others of the Garvey line…

ML: It wasn’t like a soccer match…

CR: For example, when we think of Garveyism and what happened in the United States in terms of that movement, we’re talking about a mass movement that reached the Black working class as a whole…

ML: But labor issues weren’t felt over here, were they?

CR: We have no evidence that the African National Party had a recruitment base in the Black working class. Despite this idea of a very White Portugal, there are several signs that there was a Black population, mainly a poor one, working in Lisbon, and we sought to leave several clues about this in the book.

ML: The Pan-African Congresses are contemporary with the Bolshevik revolution, I’m wondering if, in the midst of the debate on conscience and class struggles, there was already talk of a “Black proletariat”?

PV: There’s an article in the newspaper A Mocidade Africana, titled “Mundo Negro: o proletário negro,” which portrays this sector in Lisbon.

ML: What influenced this generation more: the international alliances or the insurrections coming from the colonies in Africa? Or how do these come together?

CR: It’s a combined path.

PV: The Liga dos Interesses Indígenas de São Tomé predates the Junta de Defesa dos Direitos de África in Lisbon, the political movement in São Tomé will be very influential in this generation’s reality, as many of them come from there.

ML: But did they pay attention to what was happening in Africa? These newspapers criticized colonialism, some more than others, but they also named and reflected on the resistance that existed there, in the Campanhas de África, etc. Were the resistances there seen as an inspiration for Blacks in the diaspora?

JP: These things are combined. In this book we have tried (and those who read it will judge whether we have succeeded) to take into account that the world of the so-called Metropole and the world of the African territories occupied by Portugal are not watertight realities, they communicate. This is evident to us, since these people came to Lisbon from Africa when they were children. We also have people with some political experience who are in Lisbon doing militant work, activist work. And we also have, for example, Ayres Menezes, who was at the foundation of O Negro and came to the conclusion, “Why are we here in Lisbon if the work needs to be done in Africa?” Political activity in Africa feeds political activity in Lisbon, which in turn feeds political activity in Africa. So, there’s a constant back and forth, but there’s something else. Racial discrimination, both in the colonies and in the metropolis, was felt by people who wrote in newspapers and who were politically active. It was felt by the Black population in general, of course, but it was reflected in the press, and this is echoed in a series of demands that had to do with the reality in Lisbon and in the occupied territories in Africa. For example, when O Negro talks about discrimination against Black students in Lisbon, it’s talking about racism in Lisbon. When the Black press denounces the barriers, the limits to access and development in public administration for qualified Black people with access to education, when placed on an equal footing with White people in the occupied territories in Africa, it is reflecting on racial discrimination in the colonies.

CR: Gender issues too, sometimes in articles, sometimes in short stories (the newspapers have lots of poems, short stories, novels), they also denounce sexual abuse on the cocoa plantations in São Tomé. They talk about the hut tax and how the way this tax was levied generated a series of strategies from the people. In the end, Black women were left at a disadvantage.

ML: Namely, it led to prostitution.

CR: The debate on racism, the criticism of racism, the notion that racism exists, are obvious. Take José de Magalhães, a figure with a more conciliatory stance, let’s say, in a speech at the 1919 Congress he asks “there is a pseudo-science out there that talks about superior and inferior races, but we are here to say that this is not the case”.

ML: The debate was also on a scientific level.

PV: José Magalhães was a scientist, a doctor.

CR: Going back to Du Bois: it’s one thing whether he understood the racism in Portugal and another thing is what he decided to say about it. Because, seeing the overview at the time, he may even have understood it and strategically decided to say something else. But even José de Magalhães, in a speech to the Pan-African Congress, would say it existed. That is crucial for us to realize today, in the face of the lusotropicalist idea that the Portuguese are not so racist, that this generation and what they wrote in the newspapers prove that people were very aware that this was not the case at all.

ML: The Colonial Act of 1930 defined who was civilized and who was indigenous, all these demarcations, and encouraged greater occupation in Africa. Does the generation you’re addressing still feel the echoes of this? The exhibitions, the Industrial Exhibition in Lisbon (1932), the Colonial Exhibition in Porto (1934) after the Colonial Act are referred to and criticized in Black newspapers.

CR: One needs to see that their criticism of colonialism is not yet anti-colonialism.

ML: Well, there are various tendencies there too. Such as Virgínia Quaresma, who was in favor of the empire.

CR: But Virgínia Quaresma was a Black feminist woman, the first journalist, but she wasn’t from the “Black movement”, any more than Domingas Lazary do Amaral was.

PV: Between 1926 and 1933, when you read the press of this generation you have to look even more carefully. We’re talking about a period of strong political repression. So you always have to understand that when they’re talking about something, they may not be talking about it fully or they may have changed the text, or the text may have been banned.

ML: From 1926 onwards, with the military dictatorship, did you immediately notice the restriction of freedoms in the press?

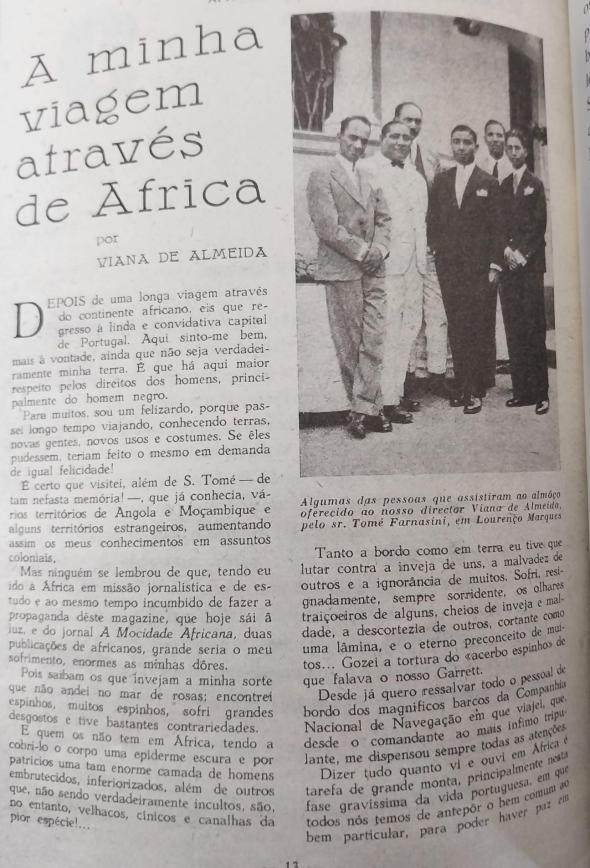

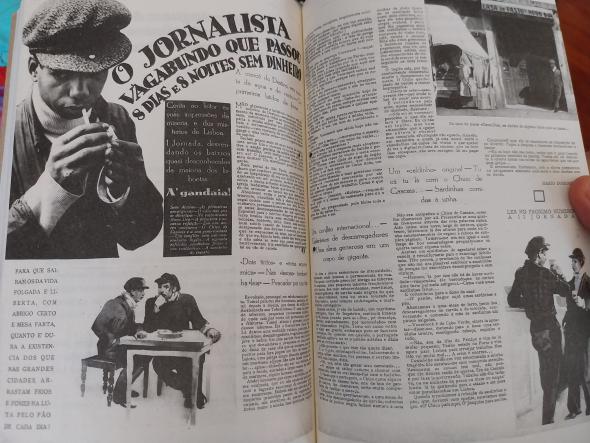

Viana de Almeida’s voyage, Africa Magazine (1932)

Viana de Almeida’s voyage, Africa Magazine (1932)

PV: Censorship appears, photographs of people from the dictatorship start to appear. We have to recognize that it was also a time when even sectors of the workers’ movement may have been co-opted by some of the military dictatorship’s discourse. It’s a whole era that’s difficult to fully understand by looking at the press. We realized that this Black movement was repressed and that was something we didn’t know before we started structuring this book. We explored the PIDE archives and discovered, for example, that two of the main activists of this generation would be persecuted. There was the question of how this movement disappeared. And there may or may not have been some connection to the dictatorship. What we do know is that some of the activists we discovered in the PIDE archives would be persecuted by the regime. João de Castro, the main activist at the end of this movement, was arrested in 1941, then persecuted in the 50s when he tried twice to launch a newspaper, O Negro e o Branco, that was seized by PIDE, and which already spoke of some independencies. And Viana de Almeida, another of the main activists, was arrested in 1937. Viana de Almeida is an interesting character because, unlike most of them, he didn’t come to Portugal young. He grew up in São Tomé where he was an activist, then went to Angola where he met other activists. It wasn’t until the late 20s that he came to Portugal. He was arrested in Mozambique in 1937, taken to the Caxias Fort where he spent several months, accused of wanting independence and of being a Marxist.

CR: And not knowing this could give rise to readings about the extent to which this generation was co-opted by political and colonial power. This was fundamental to us. Because although there were different strategies, some more conciliatory and reformist, others more critical, in truth there was also persecution, both here and in the colonies (even more so in the latter).

ML: About the various statuses and disputes of that generation which then ended up fading away. Do you suppose that the background in São Tomé, especially where there were fieldworkers or their sons, and then the petty bourgeoisie more closely linked to the PNA, that these basic differences could be related to the dissent between the Liga and the PNA? About what was happening on the plantations, the forced labor, and in the future, the hired labor, the League of Nations drawing attention, the British accusations (albeit disguised as human rights), directed at São Tomé. Did the land ownership and class origins of these São Toméans condition their view of forced labor and a regime as oppressive as the plantation?

CR: Of course, I mean, class origin is always an influence.

ML: They could be against their class, to kill it, as Cabral proposed… (laughs)

CR: That was a step that only came later, and maybe it was necessary for this generation to exhaust a certain path and for other things to have been offered. We noticed these slight differences in class fractions between the African National Party and the Liga Africana. We can’t analyze everyone who took part, it’s always conjectures, some of which are more supported by data than others. The African National Party, in addition to this slightly more Garveyist discourse, which is also a certain resistance to whitening, in the Liga and also in Du Bois’ line, this is not so present, it was that idea: we can be as good, as “civilized”, so to speak, as a “White person”.

ML: The same Du Bois who said that the “problem of the 20th century was a problem of the color line”?

CR: Du Bois lived for so many years and made so many contributions… the Du Bois of the Talented Tenth is not the same as the one who will come later, he will reformulate himself. It’s the African National Party that will systematically have some kind of reference to the gender issue (when compared to the Liga).

A Voz de Africa (1929)

A Voz de Africa (1929)

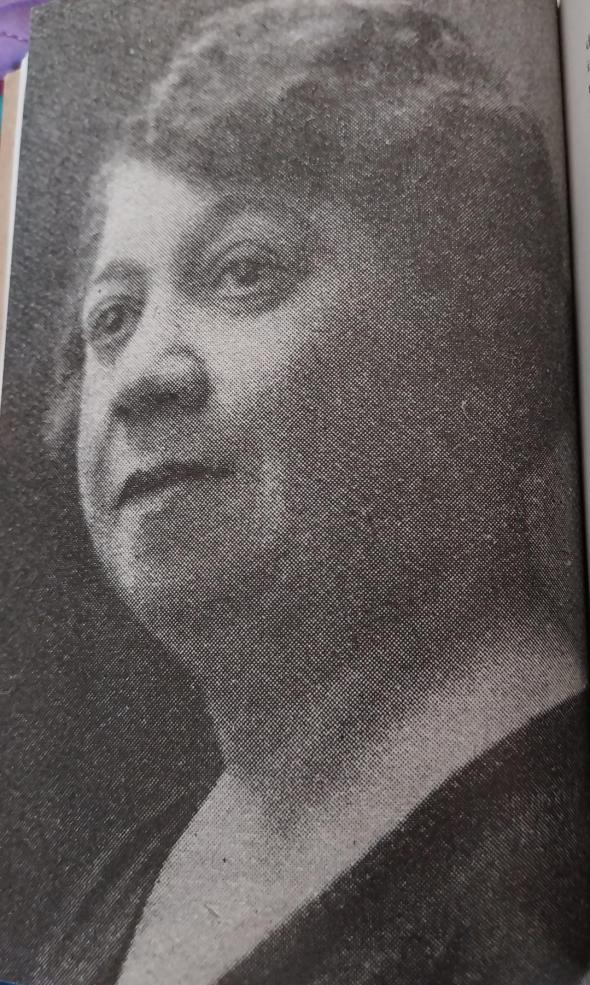

Georgina Ribas, Africa Magazine (1932).

Georgina Ribas, Africa Magazine (1932).

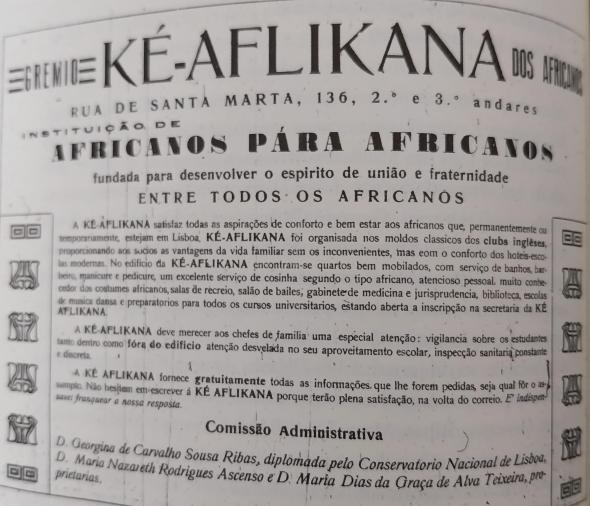

Black women’s organizations like the African Women’s League, the Ké-Aflikana, the African Guild itself (Georgina Ribas is on the board, the headquarters is her house), where a third are women, and women like Georgina Ribas, Maria Nazareth Ascenso, Maria Dias D’Alva Teixeira, are linked to the African National Party. It’s also in the sphere of influence of what would become the PNA that the issue of suffrage would be more supported and that it would be said that women should have the right to vote.

ML: Mário Domingues also wrote a text about women’s access to the vote.

CR: The figure of Mário Domingues will come into play here in a particular way.

ML: Returning to São Tomé, where Mário Domingues was from. The plantation is the laboratory of the colonial power relationship.

CR: Please note that what we think of today as colonization, the word colonization, wasn’t recognized by them in exactly the same terms. And there was a search for a certain possibility of modernization.

ML: But was the term often used lexically by the state abroad? I have no idea whether the colonial program was spoken of as such or used more as “civilizational.” In the colonial exhibitions there was no hesitation in the terms, the Monument to the Portuguese Colonization Effort is one proof.

JP: The terms colonialism and colonies have a history when it comes to their use. For example, the Colonies Ministry wasn’t always called that, in the 19th century it was called the Overseas and Navy Ministry. But this shouldn’t make us lose the sense of a very important thing. The practices were there. There’s no possible way of relativizing this…

ML: I was thinking about what Cristina was saying. If the concept isn’t used by the power, then the counter-power and counter-narratives might not use it as such either, it’s not that the practices weren’t known or that they had no notion of the deception that was a political program that claimed to be “civilizational”…

ML: I was thinking about what Cristina was saying. If the concept isn’t used by the power, then the counter-power and counter-narratives might not use it as such either, it’s not that the practices weren’t known or that they had no notion of the deception that was a political program that claimed to be “civilizational”…

JP: We’re having this conversation with someone who is reflecting on the book, and that’s interesting because it makes us focus on aspects we may have missed. But what I want to emphasize is that the reflection on the practice of colonialism is present, although, as has been said, this generation is not anti-colonialist in its strictest sense. We must, however, highlight the Mário Domingues’ positions in favor of the independence of the African peoples as the great exception to this picture, which, moreover, would undergo significant changes after 1945. These activists were critical of the practice of colonialism, although certain sectors harbored the expectation that some of the practices of Portuguese colonialism could be reformed in the sense of bringing progress to the Black communities living in the colonies. Schools, hospitals, roads…

ML: And they’re still trying to acquire rights and not necessarily calling everything into question at once?

JP: Because this generation doesn’t criticize the concept of civilization, it mobilizes the concept, thinking that civilization brings social, economic and cultural development to African communities. And they’re going to criticize colonialism and the promises of the First Republic for not having taken the ideals of the French Revolution, of the Enlightenment, to their ultimate consequences, seen not as that Eurocentric philosophy, but as the bearer of cultural, economic and social development for the communities. And herein lies the great contribution of this generation, which has to do with something we were talking about earlier. What is this generation’s relationship with forced labor? At times it will be a denunciation of forced labor, namely by sectors linked to the African National Party. Because some information would be echoed, according to which Nicolau dos Santos Pinto, from the Liga Africana, argued that there was no slavery in São Tomé and Príncipe. We don’t know to what extent this was said in the exact terms in which the accusation arose, what is certain is that it generated a discussion about the nature of work in São Tomé and Príncipe, and how it could constitute forced labor and other situations analogous to slavery, this in 1921.

ML: 160 years after the official abolition of slavery in Portugal…

JP: It should be noted that Nicolau dos Santos Pinto was the person who had the strongest links with the plantation system in São Tomé and Príncipe within this generation. Later, figures linked to the African National Party would take positions perceived as denying the accusations of forced labor and practices analogous to slavery, when these arose under the cover of the Ross Report (1925).

CR: Once again, we don’t have proof of that. We know that there are those who have accused the African National Party of having given in.

PV: As for the divergences in the movement. When we started thinking about this a few years ago, maybe we tended to take the arguments and accusations they made against each other as true. “Nicolau dos Santos Pinto made this speech at the Pan-African Congress denying forced labor.” And we tended to assume that this accusation was true. But as we got to know the movement from the inside, the disagreements, the disputes, partly due to egos, etc., we realized that when we say they were accused, it means they were accused by someone. Nicolau Santos Pinto is accused of having made a speech saying that there was no forced labor, but someone accused him. And we haven’t found any other evidence. João de Castro would also be accused, in a League of Nations structure (years after he became a critic of Nicolau Santos Pinto), of saying that there was no forced labor after all, but someone accused him. Then he wrote back saying that he hadn’t said anything like that.

ML: And, once again, these origins as fieldworkers or their children, or the status of landowners, makes it difficult to criticize what was happening in São Tomé.

CR: They have class backgrounds that make them more likely not to be able to fully criticize forced labor. They may criticize those so-called “excesses,” but they don’t say they want an end to colonialism.

We have a speech by Nicolau Santos Pinto in The Crisis where he doesn’t say anything about there being no work analogous to slavery in Portugal or in the Portuguese Empire. What he says to Black people is that, in order to achieve our emancipation, we must first have Black capital and only then advance towards rights. On the other hand, you have to think, and this is very specific to the reality of the Portuguese empire - the semi-peripheral position - that they are worried about the fact that other European colonial powers have pretensions to occupy their territories. In fact, there were concrete examples. So, beyond their class affiliations, beyond oppression, beyond hegemony and a set of ideas of the time, there was always this question. The possibility of those territories that were occupied by Portugal, for example, passing to Germany. That was on the table.

ML: And the plantation model was something consolidated as a configuration of work and a small state. The big house and the senzala (slave quarters), the plantations with a church, a school and a hospital.

CR: Yes, in some cases they didn’t think it was too little. We just need to think that in colonized spaces you don’t have a school network… They were also thinking about schools, health, infrastructure.

ML: Women weren’t so much present in the Black press in Lisbon as they were in the creation of meeting spaces, where they were very vocal about education. Because that would be one of the possible areas of female emancipation.

CR: When we look at the Black movement in other spaces, Black women and education is always an element.

ML: Which even converges with White feminists who, at the beginning of the century, were very attached to spiritual issues, education, culture, debate, as the only way for girls to access…

CR: I don’t know if it’s just girls…

ML: Yes, of course, but at a time when women were fighting for a series of rights, for example the right to vote…

CR: We didn’t find any evidence of that in this “movement.” We have to distinguish it from White feminism, what are priorities for one may not be for another…

ML: Until today…

CR: Yes, until today. We see that the African National Party talks about the suffragette movement but doesn’t really link it to Black women having the right to vote. It may exist, but we haven’t found Black women writing about it. The only article we found in the press we consulted, where we explicitly have a Black woman writing and criticizing, she’s criticizing the newspapers by saying “well, it’s about time we Black women… today it’s not acceptable not to be informed about the world and therefore there has to be a space for women and children in Black newspapers.”

ML: What’s this article?

CR: It’s from Úrsula Cardoso. We realize she’s Black because she says we. ‘We Black women.’

ML: One of the absences you also point out is the representation of folk figures, ordinary workers, the configuration of the masses. Didn’t the Black press give you that much access to the people, given that it’s written by those from a certain class, the elite?

CR: Mário Domingues signs the article O triunfo da raça negra (The triumph of the Black race), in ABC, where he tries to paint a kind of portrait, presenting the figure of a university student, a journalist, a ticket saleswoman, a manicurist.

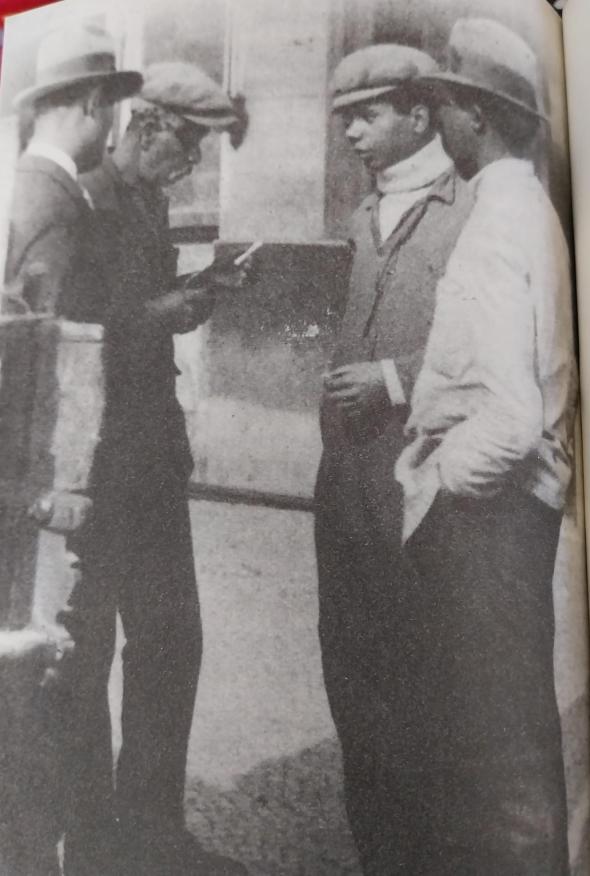

PV: There’s a photo in the article of Cape Verdean port workers at Cais do Sodré.

Cape Verdean sailors with Mário Domingues at Cais do Sodré, Notícias Ilustrado (1930)

Cape Verdean sailors with Mário Domingues at Cais do Sodré, Notícias Ilustrado (1930)

ML: The attempt to create an overview of what would be the configuration of Lisbon’s Black population is induced by data. There’s documentation of 5,000 Black people coming from the colonies, several people use this figure, which they say would represent 8%, not including those who were already in Portugal and those who would’ve come from Brazil.

CR: Because here they didn’t take into account the locals, it’s like today.

ML: The Census and the collection of ethno-racial data should’ve started back then (laughs).

CR: You have White people who were born in African territories too. You have Black people who come from occupied territories, and you have Black people who are being born in Portugal. From different historical trajectories. There is an old Black population that comes from the history of slavery in Portugal, a long and heavy history. When we look at Alcácer do Sal, for example, it also gives us food for thought. For example, José Ramos Tinhorão ends his book Os Negros em Portugal, uma presença silenciosa by talking about the whitening of the population. But was it a total whitening? How is it possible that Portugal, with such a large empire, with Brazil, doesn’t have a continually arriving Black population? Some were born in Portugal during this long history of slavery, others arrived as the fruit of other historical processes.

ML: And there’s also little knowledge about what happened after the abolition. You mention the Law of Free Birth (passed by the Marquis of Pombal in 1763 in the metropole, not in the colonies), which created a series of inequalities and injustices for those born before or after that date.

CR: It wasn’t quite like that in the Azores and Madeira, those who were enslaved came with their masters from Brazil who had conditions here, then it’s known that there was still illegal trafficking afterwards. Other White people who came from the colonized territories and brought servants with them in a practically enslaved condition. And this is totally absent from our imagination in the discussion about the post-abolition of slavery. For example, in the United States, and in Brazil too, there is a history of post-abolition. There’s evidence of Black people leaving the interior of the Alentejo in the post-abolition period and moving upwards.

PV: It’s the owner of an estate complaining “now there are formerly enslaved people wandering around.”

CR: For example, in Isabel Castro Henriques’ work on the Black community on the Sado river, one of the suggestions is that Alcácer do Sal could have been a kind of post-abolition refuge for those who came from other places, leading to the formation of a community.

ML: These are migration networks at work…

CR: And if we’re not sure about these things, at least they allow us to counter a totally White conception of Portugal at that time.

ML: It doesn’t really make sense for there to be ten percent of the population in the 17th century that then disappears…

CR: With an empire of this size, and people moving around… It’s no longer our historical period, but one of the great leaders of the Black brotherhoods and sisterhoods is Pai Paulino. He’s Brazilian, from Bahia, and he’s in Lisbon with Black people who come from other places, others who were born here. We tried to create a possible imagining of the Black population’s complexity in Portugal at that time, although much more research is needed. At least to open up these scenarios, to open up the possibilities of our imagination.

ML: From the brotherhoods, you talk about the procession of the Pretos de São Jorge (Blacks of Saint George).

‘Os Pretos de São Jorge’ in the Corpus Christi Procession (1910)

‘Os Pretos de São Jorge’ in the Corpus Christi Procession (1910)

CR: Which remains, the photograph in the book is from 1910, remnants of that other period.

ML: You formulate the lack of knowledge and imagery about Black people as a gap in Lisbon’s identities. Today there are still many people who don’t feel represented in the city. You write about it, show the connections, try to map them through the streets, organizations (on a map at the end of the book in collaboration with Ana Alcântara)… You also mention a certain delimitation in relation to what has been worked on so far. That is, there are lots of studies on colonialism, on the empire, studies on anti-colonialism, but the viewpoint is mainly that of Portuguese Whites. There’s a rejection of Eurocentrism and a search for new viewpoints in this approach to history, the care taken to start from sources produced by Black people. This is one of this book’s recognitions as a knowledge tool for the younger Black generations who are searching for themselves. Is it a program?

CR: I wouldn’t call it a program. It’s more of a look at Blackness in Portugal from a different analytical perspective.

ML: The challenge is doing it from Lisbon, to think about everything else, despite the ramifications and influences everyone had. How does this extend from the Lisbon of the early 20th century to the Lisbon of today?

JP: As the writers of this book, and also the community of Africans who currently live in Lisbon, we are trying to destroy a very heavy reality which is this issue of Eurocentrism, which is reflected in what we call the heavy colonial legacy. African countries have achieved their independence but there are phenomena, metastases of colonialism that persist in being born, in surviving, and that resist the most potent therapies we can apply. I’m trying to draw an analogy here with medicine and physiology. Medicine is trying to find a cure for cancer and we are trying to confront this heavy colonial legacy, through political activism, through research, through cultural resistance, through artistic resistance, through the work of producing knowledge that has a social and political meaning. We’re looking for tools that can annihilate colonialism once and for all and to question what is at the root of colonialism, the social organization from which it all comes.

ML: Collective memory is also the target of this attempt at change.

JP: It’s the reconstruction or reconfiguration of a collective memory. We’re talking about a collective memory that is very univocal, very one-sided. What we’re trying to say is that this collective memory is made up of many different parts and is often in conflict.

CR: You were asking where we stand… The book doesn’t fall out of the blue, it appears in a very concrete political and social context and it’s not just here that a book on Black history is appearing in Europe, in this case Lisbon. The matter of Black Europe is on the table. And of course, in a Black history, it’s not enough to have Black characters, nor is it enough to look from the outside at the things that Black people did or didn’t do. We use the metaphor of the “internal conversation” a lot. What is the petty bourgeoisie discussing with the Black bourgeoisie? Or what are Black people in Portugal discussing with those in France and the United States? What are the Black women of the petty bourgeoisie highlighting? It’s an angle of analysis. We’re not erasing the history of colonialism, it’s there. You can’t say that it didn’t exist, or that it wasn’t relevant.

ML: Dialoguing with the existing historiography but also reviewing it from this perspective.

CR: Of course, and to say that they didn’t talk about these things and that they didn’t give substance to this reality. That’s a fact.

ML: In the sense that it’s been a closer historiography to the powers that be, or that it doesn’t embrace the Black perspective even when it’s critical. For example, there’s a big difference in treating the people who were displayed in colonial exhibitions as “indigenous villages” as Guinean or Mozambican people when talking about them, as you do Cristina, and not as images at the service of propaganda.

CR: And the Black press itself was criticizing this at the time. So, for me it’s not possible to talk about the Colonial Exhibition, the indigenous villages and what happened to Rosinha and all that, without looking at what the Black newspapers were writing about at the time. They followed it. Now this work isn’t just done through academia and thus, the idea of a politically engaged science or, given our scenario of a lack of funding for research in this area, of no debate or little dialogue with Black studies in other spaces, it leaves us needing added strength. And that doesn’t come from academia because it doesn’t give us these resources and tends to reproduce power relations.

ML: Despite your militancy or engaged science, you don’t fall into the trap of perceiving reality by omitting conflicts, and one can see that you’re careful not to romanticize or create new heroes.

CR: But we don’t downplay them either. We don’t reduce their complexity.

ML: They show that things were highly debated and that not everyone held the same opinions about the events.

CR: How did you position yourselves in the First World War? You were following everything! For example, in works that talk about the Black presence, sometimes only the figures remain.

ML: Practically just caricatures.

CR: Yes, they’re static, they’re there, in conditions of great subjection, of great violence. It’s said, but it seems there’s nothing more to tell.

ML: With the added difficulty that the collections and archives probably don’t contain much about the Black population. Reconstructing a time when there were hardly any photographs and people didn’t leave written memories. In this case, they relied heavily on the press, which is something very concrete.

CR: If there was more funding for this kind of research, they could be found, we need resources. And we need to give this type of research relevance so that we can do it and find ways of doing it. Maybe it won’t be the way we imagined, but we need people doing research in a consolidated way.

JP: That’s the only way to guarantee what has been mentioned a lot here, which is to put scientific knowledge at the service of, or to fill it with, the various perspectives that reality can have.

José Pereira, Cristina Roldão and Pedro Varela, photo by Marta Lança

José Pereira, Cristina Roldão and Pedro Varela, photo by Marta Lança

PV: It’s important to mention the importance of Black people being part of these studies. Our book is written by two Black people and one White person, so for us this Black perspective is fundamental. In Portuguese academia, unfortunately, there is still very little internal criticism about the importance of having Black people studying Black and African history. And our book makes that explicit.

JP: We really need to make a Copernican revolution in the way colonialism is studied in order to put Black people at the center of the study, discussion, perspective and production of knowledge.

CR: This isn’t to say that what has been done doesn’t matter, it’s just that this dominance can’t continue. And when you want to talk about “the place of speech”, some people take that to mean that White people can’t speak. We’re not saying that, we’re saying that Black people have to. It’s one thing to write a story about Black people in Lisbon, it’s another to talk about a Black Lisbon. How has the city itself and its organizations been influenced by Black people? How they imagine doing this work is such an enormous passion. So far.

PV: One of the new things that appears in our book is the relationship between this Black movement or Black activists with what would have been the left or the workers’ movement of the time. So we have a character like Mário Domingues, who would be fundamental in anarcho-syndicalism, and who entered the “Black movement” at a later stage, at the end of the 20s, but who was mainly an anarcho-syndicalist. And we have João de Castro, who was a member of the Portuguese Socialist Party (nothing to do with today’s Socialist Party) at the time of the Socialist International. It was the most left-wing party in Parliament, and he was the only MP to represent that party in Lisbon. In the midst of all this, we discover that João de Castro was part of “extra union meetings”, which brought together people who came from the maximalists, people who came from the Portuguese Socialist Party (already after the Bolshevik revolution) and anarchists. At these meetings, they decided to create a communist party. And João de Castro was a key person in those meetings, we don’t know if he had anything to do with the future Portuguese Communist Party, but he was at the meetings where they decided to create the PCP. At the same time, this brings us up to date, to the activists who later disconnected from the workers’ movement and the left, and the relationship between the Black movement and the left, these tensions existed at the time.

ML: Once again you can draw parallels between periods.