blackness

Posts com a etiqueta blackness

Arquivo

Autor

- administrador

- adrianabarbosa

- Alícia Gaspar

- arimildesoares

- camillediard

- candela

- catarinasanto

- claudiar

- cristinasalvador

- franciscabagulho

- guilhermecartaxo

- herminiobovino

- joanapereira

- joanapires

- keitamayanda

- luisestevao

- mariadias

- marialuz

- mariana

- marianapinho

- mariapicarra

- mariaprata

- martacacador

- martalanca

- martamestre

- nadinesiegert

- Nélida Brito

- NilzangelaSouza

- otavioraposo

- raul f. curvelo

- ritadamasio

- samirapereira

- Victor Hugo Lopes

Data

- Abril 2025

- Março 2025

- Fevereiro 2025

- Janeiro 2025

- Dezembro 2024

- Novembro 2024

- Outubro 2024

- Setembro 2024

- Agosto 2024

- Julho 2024

- Junho 2024

- Maio 2024

Etiquetas

- A Experiência Afro-Brasileira na Tela

- arquivo EPHEMERA

- bissexuais

- Capacitação

- chelas

- Cindy Sissokho

- concessões ultramarinas

- Curating and the Legacies of Colonialism in Contemporary Iberia

- guia turístico

- heranças e inovações

- imagination

- José Antunes Ribeiro

- Ligia Lewis

- Marta Lança

- paulo moura

- prémio Camões

- Problemas do Primitivismo

- raça

- recolha

- tambla

Mais lidos

- AFROTOPIAS: artistas do pós-independência 17 Abril I Bruxelas

- 7th Queering Afro-Luso-Brazilian Studies Conference

- PÓS-MUSEU: 'A' de Ausência

- Uma Ecologia Decolonial - Conferência por Malcom Ferdinand

- Hanami, a primeira longa-metragem da realizadora Denise Fernandes, Cabo Verde

- Paisagens de Fogo: Uma história política e ambiental dos grandes incêndios em Portugal

- Programa de apoio à pesquisa das coleções fílmicas da Cinemateca Portuguesa-Museu do Cinema (2025)

- Orlando Pantera, de Catarina Alves Costa

- Curadoras macaenses da Bienal de Veneza apresentam nova mostra

- Mário, 14 e 15 de Maio

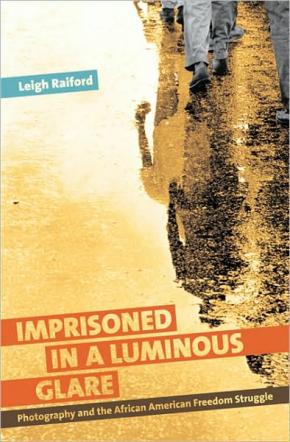

In his 1963 book, Why We Can’t Wait, Martin Luther King argued for forcing oppressors to commit their brutality in the open. Only then, he said, could activists flush oppression out of “dark jail cells and countless shadowed street corners” into “a luminous glare.”

In his 1963 book, Why We Can’t Wait, Martin Luther King argued for forcing oppressors to commit their brutality in the open. Only then, he said, could activists flush oppression out of “dark jail cells and countless shadowed street corners” into “a luminous glare.”