What’s New in Viewing Blackness

In his 1963 book, Why We Can’t Wait, Martin Luther King argued for forcing oppressors to commit their brutality in the open. Only then, he said, could activists flush oppression out of “dark jail cells and countless shadowed street corners” into “a luminous glare.”

In his 1963 book, Why We Can’t Wait, Martin Luther King argued for forcing oppressors to commit their brutality in the open. Only then, he said, could activists flush oppression out of “dark jail cells and countless shadowed street corners” into “a luminous glare.”

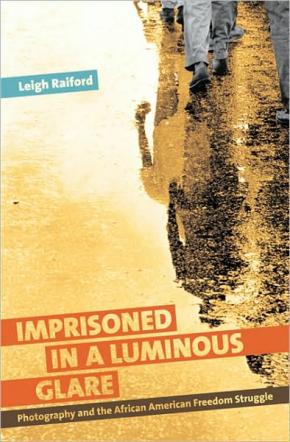

That advice suggests the nature of Leigh Raiford’s Imprisoned in a Luminous Glare: Photography and the African American Freedom Struggle, due for release in February by the University of North Carolina Press.

Raiford, an associate professor of African-American Studies at the University of California at Berkeley, examines the role photography played in three social movements—anti-lynching, civil rights, and black power. In each, she says, activists used photography to reframe African America. They sought “to both unmake and remake black identity” by, for example, challenging demeaning representations of black Americans as ignorant and unfit for citizenship.

On the phone from Berkeley, Raiford says she came to her project remembering iconic photographs, and realizing her indebtedness to African-American social movements. Of her generation—black scholars now finding their feet in academe—she says: “The way we learned history was through images.”

The relation of images to African-American life has become a much-studied subject matter for scholars like Raiford. They have been inspired, she says, by scholars like Jamaican-British cultural theorist Stuart Hall, who suggested ways in which visual images constitute ideas about race, and more recent researchers like Shawn Michelle Smith, an associate professor of visual and critical studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago whose books have included Photography on the Color Line: W. E. B. Du Bois, Race, and Visual Culture (Duke University Press, 2004). There, Smith argues that Du Bois’s own photographs challenged imagery conventions of his day—those of early-twentieth-century scientific typologies, criminal mug shots, racist caricatures, and lynching photographs—and brought to visual life his key theoretical concepts such as the color line and double consciousness.

Such books—and a slough of new and forthcoming ones—seek to ”dislodge some of the limited frames in which the thing called black art has often been discussed” by art historians, Raiford believes. New books range from general theoretical studies of how blackness has been viewed in American culture and art criticism to works that approach the same issue through narrower focuses, including museum exhibitions, pornography, black power, and lynching. Due out next month is Troubling Vision: Performance, Visuality, and Blackness (University Of Chicago Press) by Nicole R. Fleetwood, an American-studies scholar at Rutgers University who analyses a persistent presumption in American culture: that seeing blackness is problematic.

A 2007 book, hailed for broaching that issue in visual studies, was How to See a Work of Art in Total Darkness (MIT Press), by Darby English, an art historian at the University of Chicago. He argued that black artists’ work is almost always viewed reductively in terms of its “blackness” and way of “representing” race, almost as if addressing those were cultural obligations of black artists. Instead, he argues, many contemporary African-American artists encourage viewers to see their works’ historical, cultural, and aesthetic dimensions on their own terms.

Also hailed as “paradigm shifting” by colleagues was Jacqueline Najuma Stewart’s award-winning book on black cinema, Migrating to the Movies: Cinema and Black Urban Modernity (University of California Press, 2005), which looked at how African-Americans related to cinema at the dawning of the art form, and at a time of mass black migration from the rural South to the urban North.

Raiford says she knows of colleagues preparing books on such topics as depictions of African-Americans in graphic novels and on the history of black women in pornography. All these visual images encourage exhibition. And that too is under study.

Forthcoming next summer from University of Massachusetts Press is Exhibiting Blackness: African Americans and the American Art Museum, by Bridget R. Cooks, an assistant professor of art history, African-American studies, and visual studies at the University of California Irvine. Cooks examines the representation of African-American culture in mainstream art museums—demeaningly, when curators have taken an ethnographic approach that has focused on artists rather than their art; and more encouragingly, when they have adopted a recovery narrative aimed at correcting past omissions.

Unsurprisingly, most prominent among new work in black visual studies have been two subjects that are particularly striking, visually: black power and lynching.

Among recent books on black power’s visual impact have been The Black Panthers: Photographs of Stephen Shames, (Aperture, 2006), a visual survey of the group’s early years by an insider photojournalist; Black Panther: The Revolutionary Art of Emory Douglas, edited by Sam Durant (Rizzoli, 2007), about the iconic collages of photographs and his own drawings created by the Panthers’ Minister of Culture; and Framing the Black Panthers: The Spectacular Rise of a Black Power Icon (New Press, 2007), in which Jane Rhodes examined ways that black-power militants captivated and were courted by the news and entertainment media.

More recently, Amy Abugo Ongiri, of the University of Florida, contributed Spectacular Blackness: The Cultural Politics of the Black Power Movement and the Search for a Black Aesthetic (University of Virginia Press, 2009), about how the Black Arts movement and black power related to popular culture.

Among recent books relating to lynching have been Violence, Visual Culture, and the Black Male Body (Routledge, 2010) by Cassandra Jackson, of the College of New Jersey. She analyzes the history of recurrent images of wounded black men – from disfigured slaves to bullet-riddled rappers—and their relation to the parallel tradition of images of the hypermasculine black male.

Focusing specifically on lynching—particularly on ways it both sought respectability among its supporters and drove its opponents to put an end to it—have been Lynching Photographs (University of California Press, 2008) by Dora Apel and Shawn Michelle Smith; and Lynching and Spectacle: Witnessing Racial Violence in America, 1890-1940 (University of North Carolina Press, 2009) by Amy Louise Wood.

Toward the end of Raiford’s book, which also devotes a great deal of attention to lynching, she asks: “Why these images now? What do they tell us about our contemporary crises?” The scholar has a ready answer to her own questions. Authors wish “to inform us that the past is not over,” to show that the images of the past” offer a charged political language through which to voice dissent.”— Peter Monaghan